In India

|

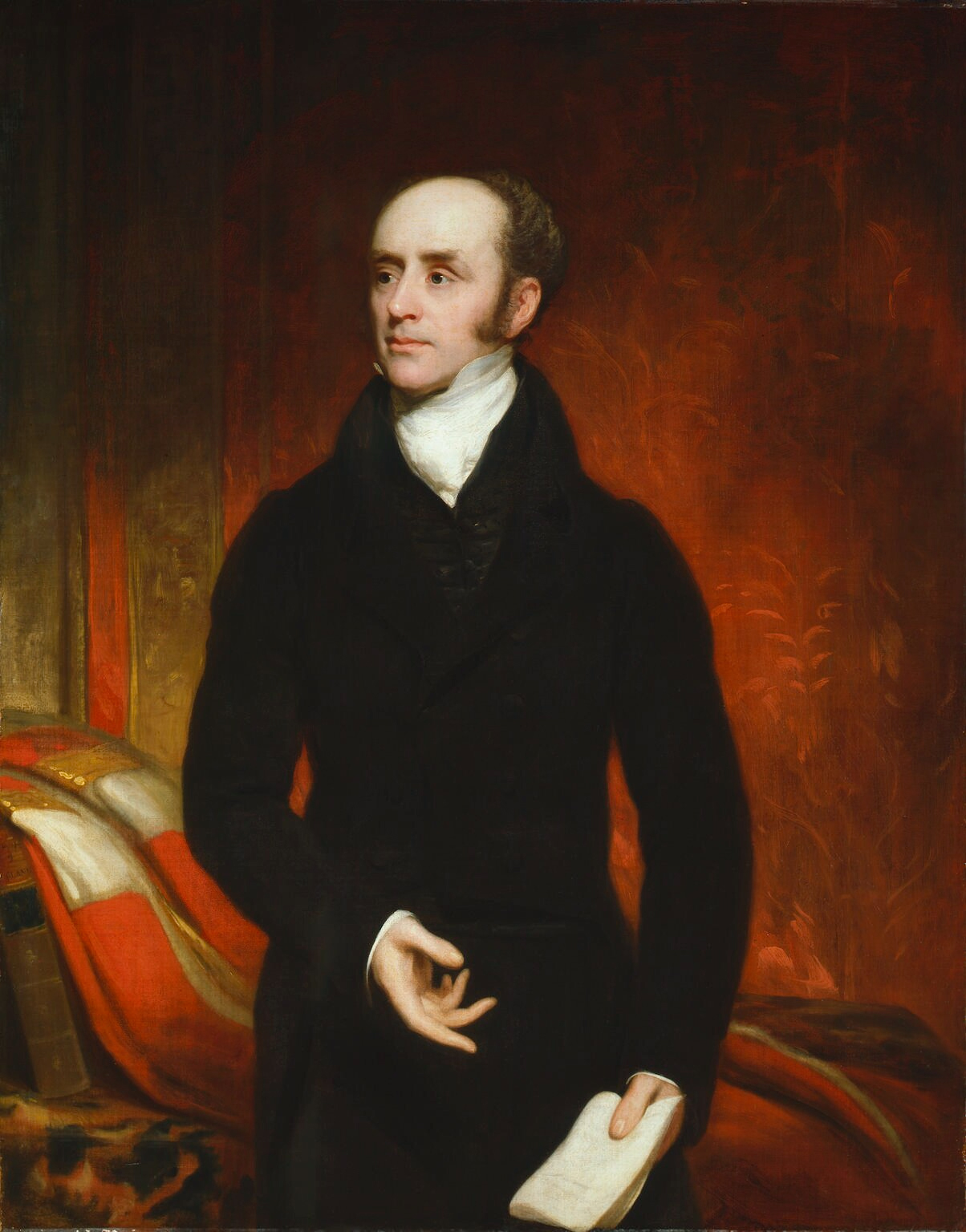

| George Eden |

In September

1835 George was appointed Governor-General of India[i]. It was from her firm sense of duty, and of course

her love for this favourite of her siblings, that Emily elected to accompany

her brother. George, Emily and Fanny arrived, along with their nephew William

Godolphin Osborne, who was to be George’s military secretary, in Calcutta in

March 1836 after a five month voyage. They landed on Emily’s birthday, she was

thirty-nine.

George had

as his private secretary John Colvin. George’s staff also included William Mcnaghten as his political secretary and his

assistant Henry Torrens.

The first 20

months of George’s appointment the Edens spent in Calcutta; during the week at Government House and at the weekends at Barrackpore

House[ii]. Emily hated the very

formal life in Calcutta; the rigorous social obligations that had to be met, no

matter how ill the climate made one feel. According to her the society was ‘second rate’ and there were very few

topics of conversation.

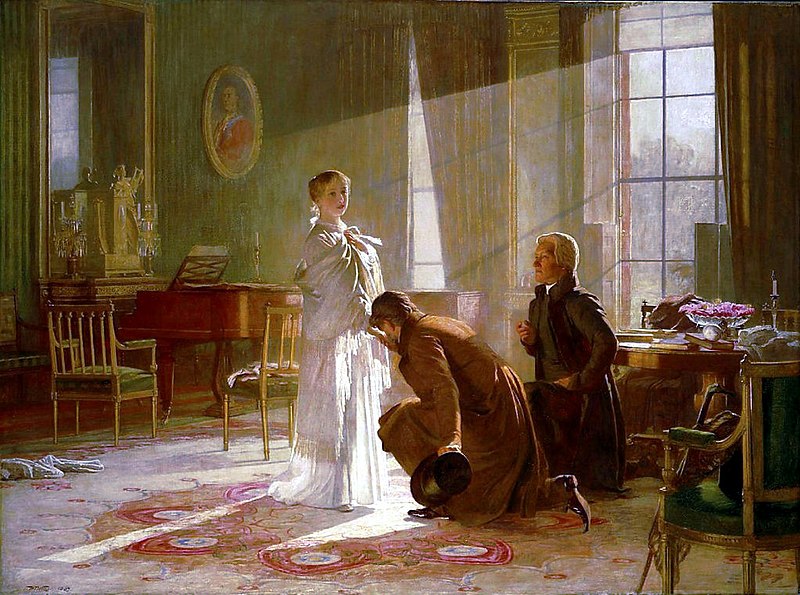

On 20th

June 1837 the old king died and in his place his young niece, Victoria, came to the throne. The inexperienced young queen was to become very

dependent on her fatherly and urbane Prime Minister Lord Melbourne. It was not

until 30th October that Emily, by then 200 miles distant from

Calcutta, learnt of the passing of an age;

‘I think the young Queen a

charming invention, and I can fancy the degree of enthusiasm she must excite.

Even here we feel it. The account of her proroguing Parliament gave me a lump

in my throat.’[iii]

Up Country

In the

autumn of 1837 Emily accompanied George on an official progress ‘up-country’ and

it is her letters to her sister Mary Drummond that give us details of the travels

of the Governor-General in colonial India. George intended to familiarise

himself with the East

India Company territory stretching from Calcutta to the River Sutlej in the north. George also wished to consolidate the 1831

treaty of friendship between Britain and the Maharajah of the Punjab[iv], Ranjit Singh.

The Sunderbunds

The party

left Calcutta on the 21st October 1837 by steamer for the first 3 ½

weeks through the Sunderbunds and up the Ganges. On 15th November the Governor and his entourage camped at Benares. By the end of November the party were travelling overland to Simla, using 850 camels, 140 elephants and hundreds of horses and bullocks.

Nawab of Oudh

There were

12,000 people travelling in the governor’s wake and it could take three days

for the ten mile long caravan to cross a river. The Nawab of Oudh sent his chef to cook for the Governor General; much

affronting St Cloup, George’s own chef, who had previously worked for the Prince of Orange. The Edens were accompanied by

George’s staff and their families[v].

At their

halts the Edens and their entourage met with the British living in the

vicinity, but of course society morality still prevailed;

‘There was a lady yesterday

in perfect ecstasies with the music. I believe she was the wife of an indigo

planter in the neighbourhood, and I was longing to go and speak to her, as she

had probably not met a countrywoman for many months; but then, you know, she

might not have been his wife, or anybody’s wife.’[vi]

Cawnpore from the Ganges

‘You cannot conceive the

horrible sights we see, particularly children; perfect skeletons in many cases,

their bones through their skin, without a rag of clothing, and utterly unlike

human creatures.’[vii]

The Edens

began distributing food, but their attempts were minimal compared to the

problems; one of the party saw three villagers drop dead of starvation. Three

days after the first distribution of supplies they came across worse

deprivation; 700 people were fed but the violence that erupted required

policing.

Victoria was

crowned on the 28th June 1838, but, so very unlike later Victorians,

Emily makes no mention of the event in her letter of that date; instead she

mentioned;

‘We had a musical dinner

yesterday; a borrowed pianoforte and singing, and two couples who accompany

each other. The flute couple I think a failure, but they are reckoned in this

country perfectly wonderful……the other couple are beautiful musicians.’[viii]

A Successful Expedition

Lord Palmerston

George was,

like Palmerston[ix], an anti-Russian politician and this led him to

dabble in affairs in Afghanistan with disastrous consequences[x]. George listened to

advisers whose proposals he believed would secure the north-west frontier. The

plan of action involved going over the Khyber Pass, at the same time marching the army through Sind in violation of an 1832 treaty[xi], using the Persians siege

of Herat as an excuse.

Ranjit Singh

had ensured that the British would take the lead in restoring Shah Shuja to his

throne. The Commander in Chief of British forces in India disapproved of the

plan and Wellington, who had served in India, thought it would mean

‘A perennial march into Afghanistan.’[xii]

Palmerston

thought that the expedition would;

‘Place the Dardanelles more

securely out of the grasp of Russia.’[xiii]

On 1st

October 1838, while staying at Simla, George dethroned Dost Mohammed[xiv] as a preliminary to the campaign. On 24th

October Emily wrote;

‘News had arrived

yesterday that the Persians had abandoned the siege of Herât, and so the

--s fancied that the Cabul

business would be now so easy.’[xv]

9,500 Crown

and East India Company troops formed the core of the

invasion force, backed up by 6,000 local troops under the command of Shah Shuja[xvi], George’s choice for leader of

Afghanistan. George and Emily attended a ceremonial parade of the troops on 3rd

December before they departed.

‘For Runjeet, instead of

being satisfied with a general view of the line, insisted on riding down the

whole of it, about three miles, and inspecting every man….……in front there was

the army marching by. First the 16th Hussars, then a body of native

cavalry, then the

Queen’s Buffs, then a train of artillery drawn by camels,

then Colonel

Skinner[xvii]’s

wild native horsemen.’[xviii]

Ghazni

Shah Shuja

entered Kandahar on the 25th April 1839

and Ghazni was taken by storm on 2rd July. The

invasion itself was a success in that on 6th August 1839, following

the flight of Dost Mohammed, Shah Shuja regained his throne; the trick would be

to keep him there. For his part in the success

George was made Earl of Auckland.

The Disastrous Expedition

Ranjit Singh

Emily

recorded Rajhit Singh’s death on 27th June

‘We heard of dear old

Runjeet’s death……It is rather fine, because so unusual in the East, that even

to the last moment, his slightest signs, for he had long lost his speech, were

obeyed.’[xix]

The

government in India was concerned that Ranjit’s death could endanger the

British lines of communication with Kabul. The Edens returned to Calcutta on

the 1st March 1840.

Dost Mohammed

Unpopular

with the Afghans, the incapable Shah Shuja was unable to secure his position in

Afghanistan without the support of the British forces and George was determined

that the army would return to India. Dost Mohammed surrendered on 3rd

November 1840 and was given sanctuary in British India; Emily drew his portrait

during September 1841.

‘I was so active

this morning. The Dost and his family all set off to-day for the Upper

Provinces, and I have done a sketch of him and his two sons – merely their

heads – and wanted his nephew, who is a beautiful specimen of a Jewish Afghan,

to fill up the sheet; so Mr. C— abstracted him out of the steamer early

this morning and brought him to my room before breakfast.’[xx]

In April

1841 George appointed Major General Elphinstone as head of the British forces in

Afghanistan, against the wishes of the Commander in Chief of all British forces

in India[xxi]. George and Macnaghten, described

disparagingly by Wellington as

‘”The gentlemen employed to

command the army.”’[xxii]

believed

they could withdraw the troops supporting Shah Shuja at a leisurely pace.

George had refused to allow proper fortifications to be built for the garrison

of Kabul[xxiii]. As an economy measure

he also reduced the subsidies given to local chiefs to keep the passes open.

Bibliography

The Last

Mughal – William Dalrymple, Bloomsbury 2006

Up the

Country – Emily Eden, Virago 1983

Heaven’s

Command – James Morris[xxiv], Penguin 1979

The Age of Reform

– Sir Llewellyn Woodward FBA, Oxford University Press 1997

www.wikipedia.en

[ii]

14 miles up the Hooghly River

[iii]

Up the Country - Eden

[iv]

Leader of the Sikhs

[v]

The trip was due to last eighteen months

[vi]

Up the Country - Eden

[vii]

Ibid

[viii]

Ibid

[ix]

Currently Foreign Secretary

[x]

George had instructions to forestall Russian encroachment towards British India

[xi]

Opening the Indus to trade provided that no munitions of war were carried on

the river

[xii]

The Age of Reform - Woodward

[xiii]

Ibid

[xiv]

Emir of Kabul

[xv]

Up the Country - Eden

[xvi]

The former ruler of Kabul; Shuja’s troops were under the command of Macnaghten,

the Political Officer

[xviii]

Up the Country - Eden

[xix]

Ibid

[xxi]

Elphinstone had no experience of fighting in the east and was ill

[xxii]

The Age of Reform - Woodward

[xxiii]

Shah Shuja had taken the citadel for his seraglio

[xxiv]

This edition predates Jan Morris’s change of gender from James

_society_beauty_and_author_by_GH,_Chatsworth_Coll..jpg)