|

| Nottingham Castle (Victorian reconstruction) |

On 30th March 1194 Richard presided at a meeting of the Great

Council at Nottingham Castle; Geoffrey was present along with his stepmother,

Hugh de Puiset, William Longchamp and Hugh of Lincoln. The great matter before

the council was what to do with Prince John who was in cahoots with Philip of

France. Longchamps was given back his old job as Chancellor while Richard paid

a ransom for the return of Walter de Coutances

‘Laden

with men, horses and arms.’[i]

Richard intended to win back his lands in Normandy, seized by Philip

while Richard was in custody. Neither Richard nor his mother were to return to England.

Instead he was to be embroiled fighting Philip and draining money from England

in times of economic difficulty. Before Richard left England he appointed Walter as Justiciar.

In the

summer, very possibly as a result of Geoffrey’s attempts to claim seniority of

York over Canterbury, Walter began an investigation into Geoffrey's actions. Walter’s

commission reported back that very little of Geoffrey’s time was wasted on clerical affairs, instead he

spent his time hawking or hunting.

Geoffrey’s quarrels with his

cathedral clergy had worsened to the point that, in one instance a member of

the cathedral chapter threw the chrism on a dungheap in protest. The canons also objected to Geoffrey

giving a large part of York's treasury toward Richard's ransom and they

objected to some of his appointments in the church of York.

This led to

Geoffrey's estates being confiscated once again. The canons Geoffrey had

excommunicated were reinstated and Geoffrey was ordered not to issue sentences

against canons without the consent of the whole body of canons.

At the end

of 1194 Geoffrey left England to appeal directly to the king who by then was in

Maine. Richard over-ruled Walter, restored

Geoffrey's estates, and pardoned him in return for a payment of 1,000 marks and

the promise of 1,000 more to follow.

A Disputatious Cleric

In January 1195 Geoffrey was ordered to appear in Rome to answer charges of simony, extortion, and neglect of his duties lodged against Geoffrey by Puiset’s supporters. The ringleaders had been excommunicated by Geoffrey who had also locked the canons out of the Minster. Geoffrey was threatened with suspension from office if he did not appear by 1st June.

Geoffrey complained to the

king, who was sympathetic until Geoffrey started rebuking Richard for his

immoral life. Richard flew into a rage and confiscated Geoffrey’s estates once

again. This loss of his estates left Geoffrey vulnerable when Walter held a legatine council at York in June 1195.

Geoffrey had managed to secure

a postponement of his case at Rome until 1st November, but was still

unable to attend, which led Pope Celestine to order that Geoffrey's suspension

should be actioned by Hugh of Lincoln. Hugh protested, and as a result

Celestine himself suspended Geoffrey on 23rd December 1195, finally

forcing Geoffrey to answer the charges against him. He travelled to Rome in

1196, where his accusers were unable to substantiate their claims and he was

restored to office by the pope.

News of Import

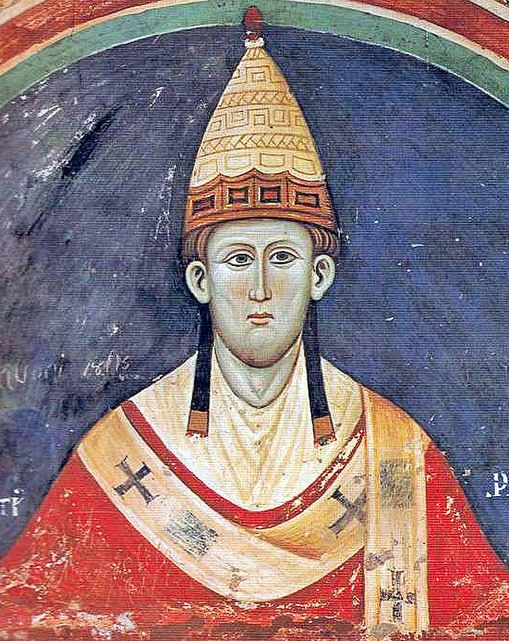

|

| Innocent III |

Eventually the new Pope Innocent III ordered on 28 April 1199 that Geoffrey was to be restored to his lands as soon as he had paid his debts to the king. Innocent further stipulated that any royal appointments in York would require papal approval.

Geoffrey’s

canons were mixed in their response to the return of their archbishop. One,

Simon Murdac announced that he would be happy to see Geoffrey return to his

archdiocese. But Murdac was immediately excommunicated by the Dean, Simon of

Apulia.

Before the

pope could make any new rulings on the dissension between Geoffrey and his

canons, the news arrived; Richard was dead. Richard died on 7th

April 1199, after a wound from a stray quarrel turned gangrenous. The lucky

shot came from one of the defenders of the chateau of Châlus- Chabrol, that Richard was besieging,. It was now the turn of Henry

II’s youngest son to reign over the empire he had wrought.

John defies the Pope

|

| Stephen Langton |

In July 1205

Hubert Walter died and John tried to replace him with one of his own supporters[ii]

who was rejected by the cathedral chapter. The stalemate continued until the

end of 1206 when Innocent III nominated Stephen Langton. John refused Langton entry to the country[iii].

John threw out the monks of Canterbury and seized the cathedral revenues.

John and

Geoffrey had enjoyed a relatively benign relationship when they were both

younger and when he came to the throne John was prepared to be conciliatory to

Geoffrey. He had enough on his plate with Arthur of Brittany also claiming his

throne[iv].

Caught between John and Philip Arthur ended up flip-flopping to pay homage to

Philip.

In an

attempt to sort the problems emanating from York, John summonsed Simon of

Apulia to attend his court at Westminster. Simon was persuaded to accept

Geoffrey as his archbishop. In return Geoffrey recognised Simon as Dean of the

chapter. On their return to York, when the Archdeaconry of Cleveland[v] fell vacant, the two men fell out

again.

Geoffrey

nominated one of his followers, but Simon nominated Hugh Murdac. Infuriated and

his Angevin temper soaring, Geoffrey excommunicated the hapless Murdac. Both

sides appealed to John who summonsed his brother to accompany him to France.

Stupidly Geoffrey ignored the summons.

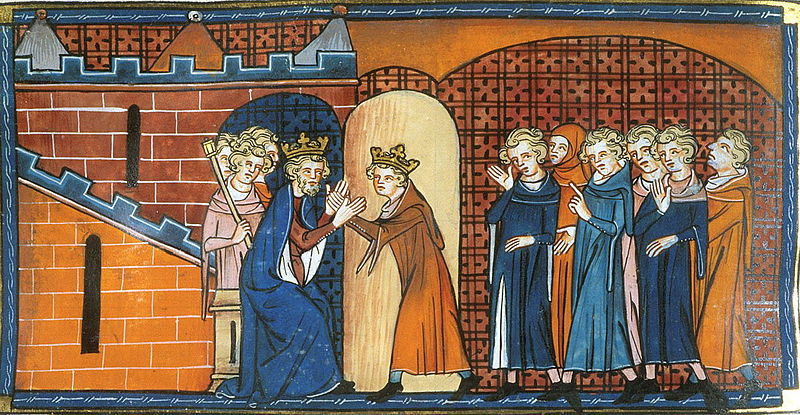

|

| Arthur pays homage to Philip |

Around the

same time Geoffrey fell out with John over taxation issues and refused to allow

his clergy to pay John’s latest tax raising whiz. The church’s lands were

seized and Geoffrey and his clergy knelt before John to plead with him for a

reversal of the seizures. Gervase of Canterbury recorded;

‘The king, in truth, threw

himself at the archbishop’s [Geoffrey] feet and laughing and jeering said “Look

my lord archbishop, even as you do so do I.”’[vi]

In the

summer of 1207 Geoffrey fled abroad, followed by a number of the senior bishops.

John seized his brother’s estates. Innocent III put the country under an interdict forbidding the clergy to take services[vii].

He also threatened to excommunicate John.

Under Interdict

|

| King John |

On 17th

March 1208 John’s officers commenced their task of seizing church properties. By

September the king was taking hostages from nobles whose loyalty was suspect. Roger of Wendover wrote;

‘King John….was afraid that,

after the interdict, our lord pope would excommunicate him or absolve the

nobles of England from allegiance to him. He therefore sent an armed force to

all men of rank….and demanded hostages of them.’[viii]

On 27th

May 1208 Innocent ordered an interdict on York should John fail to restore

Geoffrey’s property. In August he wrote to both John and Geoffrey deploring

their quarrel. Because of Geoffrey’s stance Geoffrey

of Coldingham, a

chronicler, claimed that the church in England church considered Geoffrey a

martyr.

|

| Otto IV greets Innocent III |

Innocent

excommunicated John in November 1209. John retaliated by taking over £100,000

worth of money from the clergy over the next two years. John’s treasury

appropriated the revenues of the empty benefices and managed to raise enough

money[ix]

to fund ill-advised adventures abroad.

As well as

raising the country’s military state of readiness, John set up a series of

alliances to help defend his continental possessions. He allied with his nephew

Otto IV the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles I, the Count of Flanders and a number of northern European Dukes.

Geoffrey’s

final years were spent in exile; Geoffrey died on 12th December 1212[x],

at the monastery[xi]

at Notre Dame du Parc near Rouen. He was buried there. Geoffrey

was a disappointed man whose arrogance had cost him dear.

Bibliography

Philip

Augustus – Jim Bradbury, Longman 1998

King John –

Stephen Church, MacMillan 2013

Early

Medieval England – MT Clanchy, The Folio Society 1997

Richard the

Lionheart – John Gillingham, George Weidenfeld and Nicholson 1989

The Royal

Bastards of Medieval England – Chris Given- Wilson and Alice Curteis, Barnes

& Noble Books 1995

The

Plantagenets – Dan Jones, William Collins 2012

Absolute

Monarchs – John Julius Norwich, Random House 2011

King John –

WL Warren, Yale University Press 1997

Eleanor of

Aquitaine – Alison Weir, Jonathan Cape 1999

The

Plantagenets – Derek Wilson, Quercus Editions Ltd 2014

[i]

Philip Augustus - Bradbury

[ii]

The monks nominated Reginald,

the Sub-Prior, who was set

aside by John. They then nominated John de Gray, Bishop of Norwich,

who was set aside by the pope.

[iii]

It was not until six years later that Langton was allowed into the country

[iv]

As the only child of one of John’s older brothers. In 1202, in conjunction with

Philip, Arthur waged war on Normandy

[v]

One of the riches benefices in the York Archdiocese

[vi]

King John - Warren

[vii]

No-one could get christened, married or buried in consecrated ground.

[viii]

King John - Church

[ix]

Over £100,000; Comparisons of wealth are not calculated for before the year

1270, if these monies had been extracted then not in 1211-12, then In 2014 the

relative: historic standard of

living

value of that income or wealth is £85,460,000.00 labour earnings of that income or wealth is

£1,508,000,000.00 economic status value of that income or wealth is £3,572,000,000.00, economic power value of that income or

wealth is £29,120,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[x]

The month before Geoffrey died John had agreed to accept Langton as his

archbishop of Canterbury.

[xi]

The monastery was of the Grandmontine

order; Henry II had encouraged the order to set up the monastery there and tend

to the leper house which he had set up on the site of his old hunting lodge