|

| Henry V |

Henry IV’s

bellicose heir had been champing at the bit throughout most of his father’s

reign and when his father died in 1413 Henry V immediately pressed for an invasion of England’s enemy. He

claimed the 1.6 million crowns[i] still owing for the ransom

of John II of France, captured at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, along with Philip’s grandfather Philip the

Bold. In addition Henry demanded the return of Normandy, Touraine, Brittany, Flanders, Anjou and Aquitaine; demands that were never going to be agreed. Henry also claimed

the hand of the Princess Katherine in marriage along with a dowry of 2

million crowns[ii].

The French

offered Princess Katherine with 600,000 crowns[iii] along with an enlarged

Aquitaine, an offer Henry V deemed insulting. Henry was granted a double

subsidy to allow him to take his quarrel to the French and in April 1415 the

Great Council agreed to go to war. In August the English arrived off Harfleur and promptly besieged the town, which did not surrender until early

October. Henry was left with little choice but to march through Normandy towards

the English stronghold in France, Calais.

|

| Battle of Agincourt |

John the

Fearless informed Charles VI that he had every intention of fighting for France

and would join the French army at the head of his contingent. On 10th

October the nineteen year-old Philip wrote to the gens de Compte[iv]

at Lille;

‘My father has recently

informed me of his departure with all his power to advance against the English

in the service of the king….and he wishes to have with him everyone in his

lands who is accustomed to bear arms, including we ourselves in person and[ the

Knights and Squires] of Artois.’[v]

Two days

later John wrote again to Charles to confirm the mobilisation of his men and

his imminent arrival. Philip left Oudenaarde, evidently intending to join the royal army at Rouen. The French shadowed the English army as it marched northwards. The two

armies came together at Azincourt.

But neither

Philip nor his father fought on the field at Agincourt; Philip was restrained, probably on

his father’s orders, from leaving Aire[vi], where he was staying at the time.

His uncles Anthony and Philip were not so lucky and died at the battle along

with the cream of the French nobility[vii].

Aftermath

|

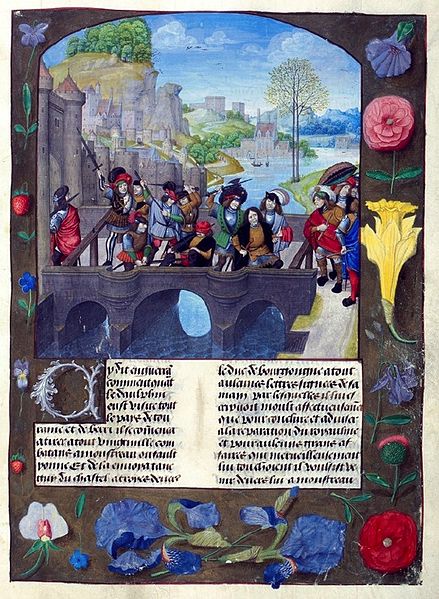

| Duke of Gloucester |

John was not

the only Duke of France to avoid death in battle. The Duke of Brittany failed to proceed beyond Amiens. John must have been pleased at the many deaths of Armagnac supporters

during the battle. The Duke of Alençon and Charles d’Albret, the Constable of France were among the dead and the young

Duc d’Orléans was taken prisoner.

Following

the disaster Henry V wanted John’s support and John and Philip travelled to Calais

to meet with the English king. Henry V hoped to gain John as an ally and

possibly a vassal; John was determined to be no such thing. The two men met in

Calais in October 1416 where John and his son were met by Henry’s brother, the Duke of Gloucester outside Calais;

‘The Duke of Burgundy was

escorted to Calais by the English, while the Duke of Gloucester was accompanied

to St

Omer

by the count of Charolais as hostage for the security for the person of the

said Duke of Burgundy.’[viii]

The subject

of the talks, attended by King Sigismund of Germany[ix] was kept secret. A draft of proposed

treaty had John agreeing to give homage to Henry V at an unspecified future

date when Henry was king of France. John did NOT sign the draft.

The

following month John entered into an alliance with Duke William of Bavaria and

the Dauphin John; John planned to install the Dauphin in Paris under his guidance.

This plan fell apart with the death of the Dauphin on 4th April 1417

and the death of Duke William in May.

The deaths of Anthony of Brabant and

William of Bavaria[x], resulted in turmoil in Brabant. The Brabantian problem was temporarily settled by Philip

under the Treaty of Woudrichem on 2nd February 1419. The treaty,

which favoured John of Bavaria, was not acceptable to Philip’s

cousin and John’s niece Jacqueline Countess of Holland and Zeeland who fell out with her husband John IV of Brabant.

Taking Control

|

| Troyes |

In April

John charged the Armagnac faction with all manner of imaginary crimes including

the murders of the Dauphins Louis and John and permitting Henry V to invade

France. The charges revivified the Burgundian-Armagnac civil war.

By October

1417 John’s army was virtually besieging Paris even as the English were taking

control of Normandy. Towns across France found themselves at odds as some

declared for John or were divided internally between Burgundian and Armagnac

supporters. John’s armies took a number of towns even as the new Dauphin Charles emerged as the leader of the

anti-Burgundian forces.

J

ohn’s men

rescued the queen from her Armagnac protectors

and the two set up an alternative government at Troyes and in January 1418 Isabeau empowered John with the same powers that she

herself had to rule on Charles VI’s behalf. Immediately Burgundians were

appointed to key roles throughout government.

|

| Bourges |

John’s men

tightened their grip round the perimeter of Paris, finally taking it 28-9th

May.

‘On this occasion the troops

met with no resistance, and there were only two or three persons killed in the

streets of Paris. These, it was said, had tried to rally support for the Count

of Armagnac.’[xi]

John followed

this coup with a reign of terror in the capital and he had the Count of

Armagnac, and as many of his men could be rounded up, put to death. The Dauphin

set up his power base in Bourges.

In August

1418, not long after regaining control of Charles VI in Paris, John arranged

the transfer of the towns and castellanies of Péronne, Roye and Montdidier[xii] to Philip. The transfer was made on

the grounds that Michelle’s dowry remained unpaid. The grant was significant in

that it extended Burgundy’s borders to the Somme.

Death of the Duke of Burgundy

Meanwhile,

as the French were distracted by bitter infighting, the English were besieging

Rouen; it fell after five and a half months on 19th January 1418.

Spring found both John and the Dauphin negotiating with the English. Between

May and June John had a series of meetings with Henry V at Meulan. They broke off without any agreement being made. John was

also negotiating with the Dauphin and in July the two men met three times,

resulting in the Treaty of Pouilly-le-Fort in which they agreed to govern

France jointly.

On 31st

July the English captured Pontoise and John took the king and queen to Champagne, breaking off negotiations

with the English. John summoned his armies and restarted negotiations with the

Dauphin. He agreed to a meeting with the Dauphin at the bridge at Montereau-Faut-Yonne on 10th September 1419.

J

ohn the

Fearless was murdered by Tanneguy de Chastel[xiii] and Arnaud de Barbazon in the presence of the Dauphin. An

enclosure was set up in the middle of the bridge, where the two men, surrounded

by their advisers, met. John knelt to the Dauphin and put his hand on his sword

when rising, possibly to aid levering himself off his knees.

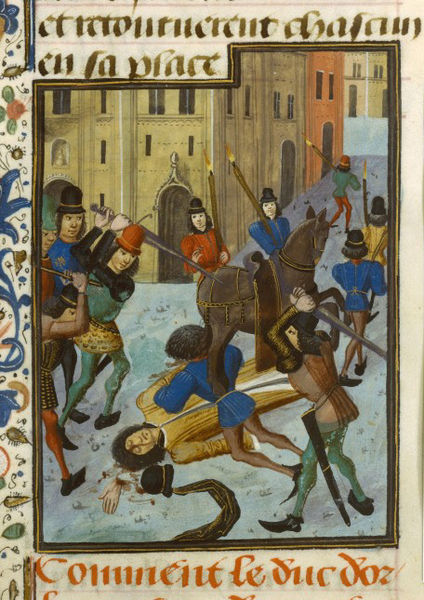

|

| Murder of John the Fearless |

One of the

Dauphin’s companions asked; John was immediately attacked with an axe by de

Chastel who did not wait for the duke’s reply. The Dauphin’s men rushed through

the door from their side of the bridge and joined in hacking John to death.

The Dauphin

and his advisers must have feared that John would take complete control of France,

including the Dauphin himself as well as his parents, and consolidate his hold

on power, possibly even overthrowing the king and making himself monarch of the

country. Several of Charles’ advisers had worked for Louis d’Orléans and saw

this as gaining vengeance for their former master’s death. The murder resulted

in a catastrophe for France when John’s son and heir Philip threw his lot in

with the English.

Bibliography

The Hundred

Years War – Alfred Burne, Folio Society 2005

The Reign of

Henry VI – RA Griffiths, Sutton Publishing Ltd 1998

Europe:

Hierarchy and Revolt 1320-1450 – George Holmes, Fontana 1984

The

Fifteenth Century – EF Jacob, Oxford University Press 1997

A Distant

Mirror – Barbara Tuchman, Papermac 1989

John the

Fearless – Richard Vaughan, Longmans, Green and Co Ltd, 1966

Philip the

Good – Richard Vaughan, Boydell Press 2014

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

In 2015 the relative: historic standard of

living value of that income or

wealth is £1,034,000,000.00 labour earnings of

that income or wealth is £12,570,000,000.00 economic status value of that income or wealth is £39,970,000,000.00 economic power value of that income or wealth is £555,000,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[ii]

In 2015 the relative: historic standard of

living value of that income or

wealth is £1,445,000,000.00 labour earnings of

that income or wealth is £12,430,000,000.00 economic status value of that income or wealth is £43,880,000,000.00 economic power value of that income or wealth is £767,300,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[iii]

In 2015 the relative: historic standard of

living value of that income or

wealth is £433,600,000.00 labour earnings of

that income or wealth is £3,729,000,000.00 economic status value of that income or wealth is £13,160,000,000.00 economic power value of that income or wealth is £230,200,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[iv]

Accounts staff

[v]

John the Fearless - Vaughan

[vii]

Charles of Orléans was taken prisoner

[viii]

John the Fearless - Vaughan

[ix]

Future Holy Roman Emperor

[x]

Leaving his daughter Jacqueline to inherit his lands

[xi]

John the Fearless - Vaughan