|

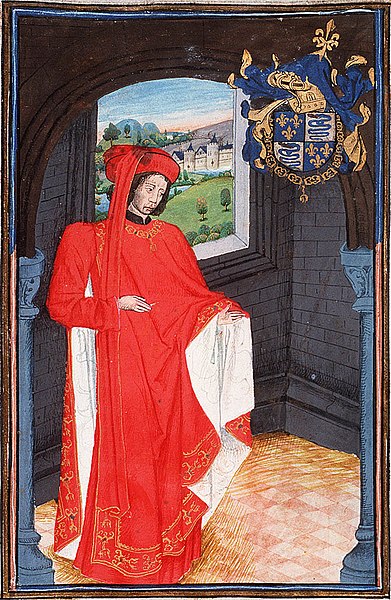

| Philip the Good |

Led by the Nose in Arras

One of the

major stumbling blocks to a treaty between the Burgundians and the French was

Charles VII’s involvement in the murder of Philip’s father John the Fearless in

Paris in 1419. Philip was assured that the pope’s[i] envoys, the Cardinal

Cyprus Hugh de Lusignan[ii] and Cardinal Albergati, would ensure that Charles did

penance for the deed.

The French

and the Burgundians signed the Treaty of Arras on 21st September 1435[iii]. Philip was not a

diplomat and was led by the nose by Charles VII who offered terms he never

meant to keep in order to detach the Burgundians from their former allies.

Charles bribed a number of important members of the Burgundian council to

encourage them to support the treaty. The bribed included Philip’s most senior

and trusted advisor Antoine, Lord of Croy [iv] along with Chancellor

Rolin.

‘To the said Nicolas Rolin 10,000 saluts[v]

To the said lord of Croy, likewise 10,000 s

To the said lord of Charny 8,000 s

|

| Antoine de Croy |

The perfidy

was not the councillors alone; Isabella too fell for French persuasiveness and

accepted a pension of £4,000 per annum[viii] as thanks for her

services as a negotiator of the Franco-Burgundian peace treaty. This was rent

monies from lands Philip had given his wife, but without Charles to ensure that

the money was paid to Isabella, she had little chance of receiving the monies.

Upon

recognizing Charles VII as king of France and returning the county of Tonnere to the crown Philip was given; the County of Auxerre and the County of

Boulogne, the cities on the Somme and Péronne, Ponthieu. The Vermandois,

with its capital Saint-Quentin.

Philip was excused from giving homage to the man he

believed complicit in his father’s murder[ix].

Problems at Home and Abroad

It did not

take long before Charles showed his true colours, he refused to undertake the

penance imposed upon him for the murder of John the Fearless[x]. Charles also ordered his

troops to attack the lands he’d given Philip and encouraged raids on the

borders with Burgundy. In addition Charles refused to recognise Philip’s

privileges due to a Prince of the Blood[xi].

The English

for their part, in retaliation at Philip’s perfidy, were negotiating trade

deals direct with the merchants of the lowlands, without going through Philip.

The Burgundians retaliated by attacking English trading vessels and piracy

abounded, causing problems for all nations dependent on trade. Burgundy in

particular was hit and Philip was chronically short of ready cash[xii].

|

| Neptune Gate, Calais |

In September

1435 John of Bedford died and his brother Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester emerged

as the most powerful figure in the English government. Humphrey’s marriage to

Jacqueline of Hainault meant he was antipathetic to Philip and now he tried to

seize Flanders.

Rumours were

rife that Philip intended to attack Calais in the summer of 1436. Philip’s army settled before the town on 9th

July, but he was unable to stop access from the sea. Running short of money

Philip wrote to Isabella pleading for funds to continue the siege. Isabella

sent 1,000 saluts[xiii]

of her own money, to no avail as Philip’s men abandoned him on 28th

July. A few months later Hue

de Lannoy[xiv]

wrote to Philip about the problems Burgundy was facing;

‘You must have appreciated,

during the siege of Calais, what harm is done by lack of finance, and it is to

be feared that the war has just begun.’[xv]

Negotiations

|

| Charles d'Orleans |

Philip

turned to his lands in Artois to mobilise another army. He informed Isabella to

meet with the leaders of Ghent, Bruges and Ypres and to negotiate a solution to

the uprisings by 13th August 1436. Philip needed to get an army in

the field to fend off any revenge attacks by the English.

Things went

from bad to worse and two of Philip’s men were assaulted, one of whom died of

his wounds. In trying to save the wives of the two men, Isabella’s convoy was

searched by angry militia. Philip himself was assaulted in Ghent on September 3rd;

his bodyguard was disarmed and he was kept prisoner by the citizens until he

agreed to their demands.

Hue de

Lannoy agreed with Philip that Burgundy needed allies at the French court in

order to persuade Charles VII to desist in his attacks on Burgundy’s frontiers,

especially as they believed that the English would once again start raiding.

Philip believed that there were two possibilities he could pursue to gain his

ends;

·

or

forgiving the 400,000 gold crown[xvii] ransom agreed when

Philip’s men captured René of Anjou[xviii]

Philip opted

to play the first card and hold René’s ransom as a backup card. After Isabella

negotiated with them, the English undertook to allow Charles of Orléans to tend

the upcoming negotiations;

‘That same autumn the Duke of Orléans, who had been

a prisoner in England ever since the battle of Agincourt, was released…..it was

hoped that his presence and influence in France would further the English

cause, and the duke undertook to do his best in the interests of peace.’[xix]

|

| Hue de Lannoy |

Isabella helped prod the French

nobility into paying up towards Charles of Orléans ransom.

Rebellion

continued to flare throughout Flanders during the remainder of the year and

into 1437 as well. The Flemings blamed Philip’s policies for the loss of trade,

they were not alone in this; Hue de Lannoy pointed out to Philip;

‘The English are planning to

keep a large number of ships at sea to effect a commercial blockade of your

land of Flanders. This is a grave danger, for much harm would result if that

country were deprived for any length of time of its cloth industry and

commerce.’[xx]

The people

also blamed Philip for the growing struggles between merchants and artisans and

rivalry among the major towns of the region. The people seemed to regard

Isabella as separate and apart from her husband; recognising that she

understood the problems facing a maritime economy.

Bibliography

The Hundred

Years War – Alfred Burne, Folio Society 2005

Edward IV –

Keith Dockray, Fonthill Media Limited 2015

Wars of the

Roses – John Gillingham, Weidenfeld Paperbacks 1990

The Reign of

Henry VI – RA Griffiths, Sutton Publishing Ltd 1998

Europe:

Hierarchy and Revolt 1320-1450 – George Holmes, Fontana 1984

The

Fifteenth Century – EF Jacob, Oxford University Press 1997

Margaret of

Anjou – Helen E Maurer, Boydell Press 2003

Louis XI –

Paul Murray Kendall, Sphere Books Ltd 1974

Prince Henry

– Peter Russell, Yale University Press 2000

Isabel of

Burgundy – Aline S Taylor, Madison Books 2001

John the

Fearless – Richard Vaughan, Longmans, Green and Co Ltd, 1966

Philip the

Good – Richard Vaughan, Boydell Press 2014

Charles the

Bold – Richard Vaughan, Boydell Press 2002

www.wikipedia.en

[ii]

Known as the Cardinal of Cyprus

[iii]

Shortly after the death of John of Bedford

[iv]

Leader of the pro-French party at the Burgundian court

[v]

On the assumption that the salut was equal in worth to the French livre then in

2015 this payment would have been worth; historic standard of

living value of that income or

wealth is £7,318,000.00 labour earnings of

that income or wealth is £59,830,000.00 economic status value of that income or wealth is £247,500,000.00 economic power value of that income or wealth is £4,461,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[vi]

Jan van Hoorn, admiral of Flanders, killed the following year by Flemings after

being accused of accepting English bribes

[vii]

Philip the Good - Vaughan

[viii]

In 2015 the relative: historic standard of

living value of that income or

wealth is £2,927,000.00 labour earnings of

that income or wealth is £23,930,000.00 economic status value of that income or wealth is £98,990,000.00 economic power value of that income or wealth is £1,784,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[ix]

Upon the death of either Philip or Charles the giving of homage for the

Burgundian lands in France would resume

[x]

To apologise for his involvement and to set up a number of religious

foundations in memory of the duke

[xii]

A frequent problem for any nobility whose worth was usually measured in lands

[xiii]

On the assumption that the salut was equal in worth to the French livre then in

2015 this payment would have been worth in 2015 the

relative: labour cost of that

project is £6,171,000.00 economic cost of

that project is £483,400,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[xv]

Philip the Good - Vaughan

[xvi]

Who had been held captive for 23 years, ever since the Battle of Agincourt; his

family had been unable to raise the ransom demanded by the English for a Prince

of the Blood. see http://wolfgang20.blogspot.co.uk/2013/04/charles-duke-of-orleans-ii.html

[xvii]

Anjou had been released in 1437; in 2015 the relative: historic standard of

living value of that income or

wealth is £224,500,000.00 labour earnings of

that income or wealth is £2,241,000,000.00 economic status value of that income or wealth is £8,615,000,000.00 economic power value of that income or wealth is £156,700,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[xix]

The Hundred Years War - Burne

[xx]

Philip the Good - Vaughan