|

| Olivier de Clisson |

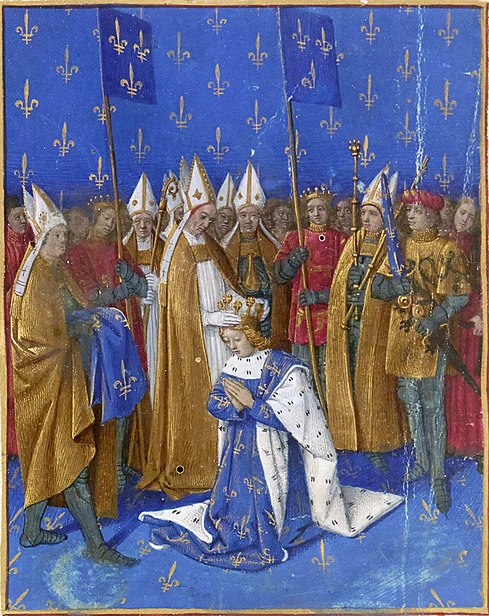

Marriage of the King

The French army

returned to Paris in January 1383; strengthened by the victory against the

rebels of Ghent. The Parisians came out in force and were ordered to lay down

their arms. The gates of the city were thrown down for the king to ride over as

he entered his capital city and the chains, that blocked off city streets, were

removed. Arms were to be handed in at the Louvre and were then transported to

Vincennes. About one hundred rebels were executed.

A sales tax

of twelve pence in the livre was instituted on all merchandise with additional

taxes on wine and salt. Back taxes were demanded and the ordinances and

privileges of Paris were revoked. The guilds were emasculated by the imposition

of supervisors appointed by the Provost of Paris.

Both Philip

and his brother of Berry were united against the encroachment of the king’s

champion, Olivier de Clisson[i]. In February 1384 the two brothers

signed a mutual defence treaty with Clisson’s enemy John de Montfort, Duke of Brittany.

|

| Charles VI (Top C) and Isabeau (Bottom C) |

In July 1385,

in compliance with his father’s deathbed wishes, Charles VI was married to Isabeau of Bavaria[ii]. Philip and Albert of Bavaria had

discussed the question of marriage between Charles and Isabeau during the

celebrations of the double Valois-Wittlesbach wedding in April. Charles was

seventeen and his bride was fifteen.

Problems

arose when the French demanded that the bride-to-be be examined by the ladies

of the court; a demand that the bride’s father refused. Charles spoke to his

uncle Philip;

‘The Duke of Burgundy came

in. ‘Uncle’ said the King, ‘it is our wish to be married in this fine cathedral

of Amiens. We do not want any further delays.’ ‘Just as you say, my lord’ said

the Duke.’[iii]

Philip and

his brother Berry were to retain the reins of government until 1388 when Charles

reached the age of twenty and took over control of his kingdom from his uncles.

Clisson boasted that it was he who had made Charles;

‘King and lord of his kingdom and taken the government out

of the hands of his uncles’[iv]

Charles

reigned with the help of Clisson and his father’s Marmousets. In November 1388, notwithstanding the blow to his pride,

Philip entertained the king, Clisson and Louis d’Orléans at his hôtel in Conflans. He also undertook

diplomatic missions on behalf of the crown to Italy in 1391 and to Amiens in

1392.

Starting a Family Feud

|

| The Madness of the King |

Charles’

independent rule lasted until 1392 when Philip was able to take control of the

kingdom’s affairs again. Charles was leading an expedition to punish the Duke

of Brittany for harbouring Pierre de Craon, who had attempted to assassinate the Constable. He insisted

that his uncles, who were allied with Brittany, accompany him.

En route,

Charles was seized by a manic fit as the company rode through the forest of Le Mans. A stranger chanced to call out to Charles as he was riding by; immediately

afterwards Charles was further startled by a page who dropped his lance.

Charles drew his sword and fell on his entourage and killed at least one of

them before being disarmed.

‘The Dukes of Berry and

Burgundy rode talking together….the page carrying the lance forgot what he was

about or dozed off…..There was a loud clang of steel, and the King, who was so

close that they were riding on his horse’s heels, gave a sudden start….he

imagined that a great host of his enemies were coming to kill him….The Duke of

Burgundy….looked across and saw the King chasing his brother with a naked

sword….Knights, squires and men-at-arms formed a circle right round the King, allowing

him to tire himself out against them.’[v]

From Le Mans

Philip and Berry dismissed the Marmousets

and disbanded the army, seizing the reins of government. Philip and Berry’s

high-handedness angered their nephew Louis d’Orléans[vi] who, as Charles’ closest relative,

considered that he should be his brother’s regent. Clisson’s injuries kept him

from supporting Louis and in short order found himself without a job; Philip

having dismissed him summarily.

|

| Attacking the Turk |

In 1396 the

Ottoman’s annual chevauchée wended

its cumbersome way to Hungary where the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund called on Christendom to defend the

country against the infidel. The call to crusade was answered by military from

across northern Europe. Philip, as a committed Christian, was ready to answer

the call and sent his eldest son John, now twenty-four, at the head of the

Burgundian army.

In September

1396 the combined armies of the French, English, Bulgarian, Wallachian,

Croatian, Hungarian and Burgundians were routed by the Ottomans led by Bayezid I. It was possibly the case that the Ottomans, with one supreme leader,

were able to offset the vastly numerically superior enemy by a unified command,

whereas the Christians had not one but eleven leaders, four of whom were taken

captive[vii].

In January

1397 Philip sent an embassy to Bayezid with gifts that he hoped would appeal to

the potentate;

‘Ten superb charges,

complete with their harness and led by seventeen grooms in white and scarlet

livery, hounds, gyrfalcons, the very finest examples of cloth and tapestry, a

dozen pairs of gloves and some choice pieces of plate.'[viii]

By June an

agreement was reached whereby the prisoners were to be exchanged in return for

a ransom of 200,000 ducats[ix]. Philip had to turn to

his subjects to raise his son’s ransom and the negotiations took months to

agree; the Flemings and Burgundians had already been paying over the odds to

fund the crusade in the first place

Regent and Patron of the Arts

|

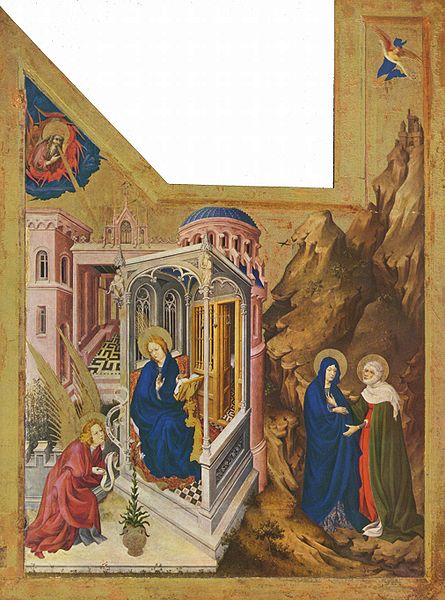

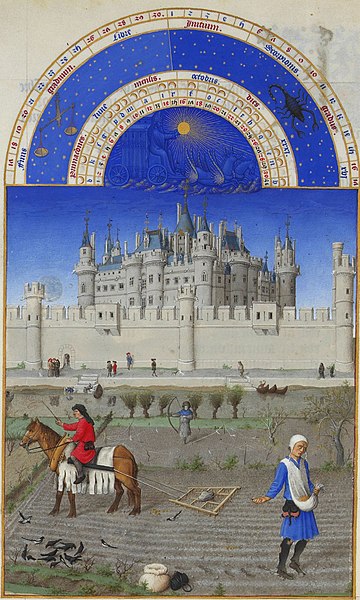

| Broederlam altarpiece |

Like all

major nobles Philip supported the arts; he was a patron of Christine de Pisan, enjoining her, shortly before his death, to write Le Livre

des fais et bonnes meurs du sage roy Charles V. Philip also patronised Honoré Bonet, the Prior

of Salon[x] and Eustache Deschamps. Philip and

his wife shared a love of books and built up two libraries in Paris and Arras.

Philip used well-known

sculptors, including Jean de Marville and Claus Suter[xi], to work on the Charterhouse of Champmol, a religious foundation he had long supported, arranging it

as a sepulchral monument for himself and his heirs. The work started in 1377,

and was built from locally quarried stone.

He also

commissioned artists to work on this funerary monument, including Melchior Broederlam who painted two wings to decorate an

altarpiece by Jaques de Braerze. Broederlam’s talents were mainly

used to decorate Philip’s castle in Hesdin. Philip first employed the Limbourg brothers who were later to work for his brother Berry[xii].

|

| Broederlam altarpiece |

Throughout

his time as Regent Philip was to find himself in conflict with his nephew

Louis, over his determination to forcibly take control of his wife’s

inheritance in Italy, over the great schism, over taxes Louis had imposed in

his territories that disadvantaged Philip’s subjects and rivalry between the

two duchesses.

In 1401 both

men mustered troops in Paris. The situation was saved by intervention from the

Queen, and the dukes of Berry and Bourbon. In 1403 Philip was able to exclude

Louis from all but a very subordinate role in the regency. He further

strengthened his position by marrying his grandchildren into the royal family. The

feud exacerbated the realm’s internal disorder and reduced the effectiveness of

foiling foreign interventions.

Philip died

on 27th April 1404 leaving his eldest son John to inherit not just

the duchy, but the ongoing feud with Louis d’Orléans which was to have tragic

consequences for France[xiii]. Philip was buried in a tomb in the palace of the Dukes of

Burgundy in Dijon. The tomb was the work of Marville and Suter and made of

black marble. Philip’s statue is guarded by two golden angels

Bibliography

Chronicles –

Froissart, Penguin Books 1968

Europe:

Hierarchy and Revolt 1320-1450 – George Holmes, Fontana 1984

The Fourteenth

Century – May McKisack, Oxford University Press 1997

A Distant

Mirror – Barbara Tuchman, Papermac 1989

Philip the

Bold – Richard Vaughan, Boydell Press 2011

The Flower

of Chivalry – Richard Vernier, Boydell Press 2003

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

He was made the Constable of France after du Guesclin’s death in 1380

[iii]

Chronicles - Froissart

[iv]

Translated from the French in Philip the Bold - Vaughan

[v]

Chronicles - Froissart

[vii]

Almost all the Franco-Burgundian army were killed or captured including John

the Fearless, Enguerrand de Coucy, Philip of

Artois and John le

Maingre, a Marshal of

France

[viii]

Philip the Bold - Vaughan

[ix]

In 2016

the relative: historic standard of living

value of that income or wealth is £155,800,000.00, labour earnings of that income or wealth is £1,417,000,000.00, economic status value of that income or wealth is £3,652,000,000.00, economic power value of that income or wealth is £88,170,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[xi]

Suter was made court sculptor of Burgundy in 1389 and continued to hold the

position until his death. The post carried the rank of valet de chambre

.jpg)