|

| Henry and Eleanor |

Henry’s

return to England was in part delayed by the hostility of Louis VII, newly

returned from the Second Crusade. He was not pleased to realise that

Normandy and England could soon be ruled by the same person and refused to

recognise Henry as Duke of Normandy. Eventually Geoffrey advised bribing Louis

by giving up the Vexin in return for recognition as duke[i]; it worked. At the end of

August 1151 Henry paid homage to the king of France for Normandy.

Less than a

month later Geoffrey died at the age of thirty-nine. Henry FitzEmpress had to

travel to Anjou to take homage from his vassals. He was then embroiled in an

affair of the heart[ii],

kept secret as his future wife was the wife of his liege lord; Eleanor of Aquitaine, Queen of France. In a fraught

divorce it was finally agreed that Louis would keep custody of the two French

princesses, their daughters and on 18th May 1152 Henry married the

heir of William X, Duke of Aquitaine[iii].

Louis then

took sides with Stephen and Eustace in a futile attempt to drive out Henry from

his lands in Normandy. Henry FitzEmpress saw off the attacks but time was

marching on and his supporters in England were crying out for his return. By

the time Henry FitzEmpress returned to England the war had turned in Stephen’s

favour; he was besieging Wallingford Castle having taken Newbury in 1152.

|

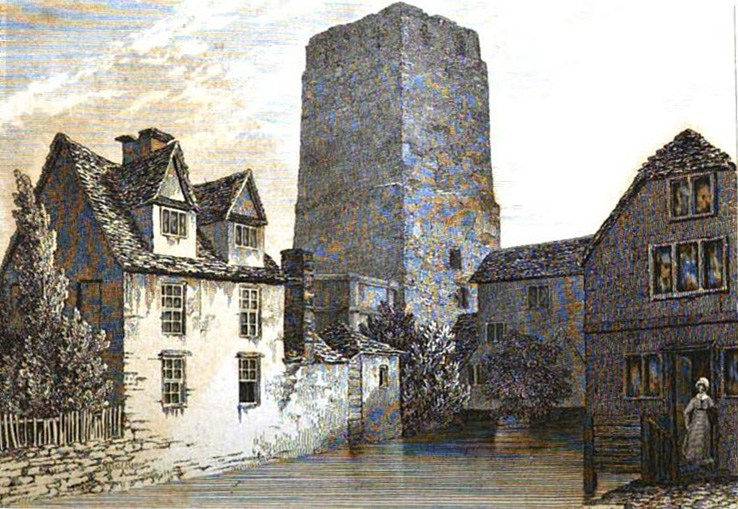

| Malmesbury Abbey |

Henry

FitzEmpress arrived on 6th January 1153 bringing 140 knights and

3,000 foot soldiers carried in 36 ships. He was hastily followed over the

Channel by Eustace. Henry made his way to Malmesbury where the castle was surrendered to him after a stand-off.

Henry then

rode to Stockbridge to meet with the Archbishop of

Canterbury and the Bishops of Winchester, Bath, Salisbury and Chichester. The purport of the meeting was to

discuss the return of Devizes Castle to the control of the Bishop of Salisbury.

This done the bishops agreed to use their best efforts to reach a consensus

between the warring parties.

Coming to Terms

|

| Wallingford Castle |

Stephen was

now over sixty and had lost his appetite for war. He had relied a lot on

Matilda of Boulogne and her death the previous summer had knocked away one of

his main supports. Of his supporters the Earl of Leicester had transferred his support to Henry

FitzEmpress who was taking control of the midlands. William d'Aubigny, Earl of Arundel argued the futility of further fighting.

By July

Henry arrived at Wallingford where Stephen was once again besieging Brian

Fitzcount’s castle. Henry’s forces in turn besieged Stephen’s wooden

siege-castle at Crowmarsh Gifford. Stephen and Henry were ambushed by

their own supporters who persuaded the two men to meet and agree a temporary

truce.

Stephen's

son Eustace opposed any rapprochement with the enemy, he clearly felt betrayed

by his father’s actions;

Eustace for his part,

greatly vexed and angry because the war, in his opinion, had reached no proper

conclusion, left his father and went out of sight of the court, and met his

death from grief within a few days.’[iv]

but he died

suddenly in the August, allegedly struck down by the wrath of God while

plundering church lands near Bury St Edmunds. Eustace’s death left the way open for the two parties to

agree peace terms.

Henry

FitzEmpress and Stephen were persuaded to meet on 6th November 1153

at Winchester. Stephen announced the Treaty of Wallingford at Westminster

Cathedral at Christmas: he recognised Henry FitzEmpress as his adopted son and

successor in return for Henry paying homage to him.

‘The king first acknowledged….the hereditary right

which the duke had in the kingdom of England. And the duke generously conceded

that the king should hold the kingdom for the rest of his life, if he wished.’[v]

Other

conditions included:

- Stephen promising to listen to Henry's advice,

but he retained all his royal powers; Henry conceded that;

- Stephen's remaining son, William,

would do homage to Henry and renounce his claim to the throne, in exchange

for promises of the security of his lands;

- Key royal castles would be held on Henry's behalf

by guarantors, whilst Stephen would have access to Henry's castles;

- The numerous foreign mercenaries would be demobilised and sent home.

|

| Cathedral cloister |

Henry less than a year to wait; the young FitzEmpress became Henry II on 25th October 1154 when;

‘[Stephen] was suddenly seized with a violent pain

in his gut, accompanied by a flow of blood.’[vi]

Matilda did

not attend the coronation but it was one of the two crowns of gold that Matilda

brought back from Germany with her that Henry wore that day.

A Mother’s Influence

Matilda had

set up household in Rouen in a residence built by her father at his park at Quevilly, on the banks of the River Seine. The house was near to the priory of Notre Dame du Pré[vii].

|

| Matilda |

It was from here that Matilda acted

as her son’s surrogate when Henry was on his travels across his vast domains.

Henry trusted his mother’s judgement; one royal mandate, issued in England to

the justices in Normandy in the late 1150s said;

‘If you do not do this let

my lady and mother the empress see that it is done.’[viii]

Matilda

appears to have persuaded Henry not to invade Ireland which he wanted to bestow

upon his younger brother William. William was given lands in England in lieu.

In 1156

Matilda was forced to preside over a bitter family conference in Rouen, after

the twenty two year old Geoffrey rose up in rebellion against his elder

brother. Henry was immovable and Geoffrey stormed off to wage war. Henry took

less than six months to take Chinon, Mirebeau and Loudun. Geoffrey ceded his claim to Anjou

and settled for an annuity He died two years later, an embittered and

humiliated young man. William died in Rouen six years later, his mother by his

side.

|

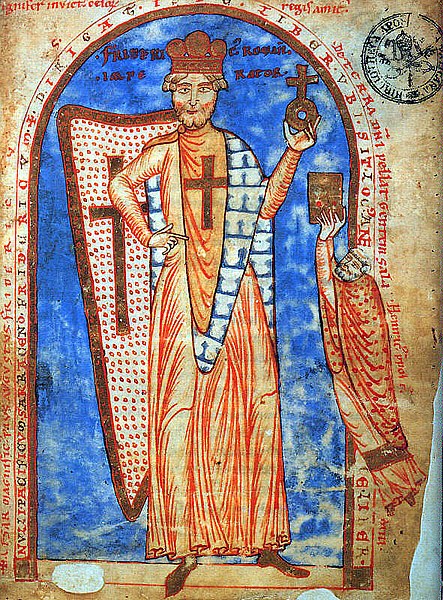

| Frederick Barbarossa |

In 1157

Matilda was probably involved in the negotiations with Emperor Frederick Barbarossa over the fate of the mummified hand

of St James which Matilda had brought to England after the death of her first

husband. The emperor wanted the relic returned to the imperial treasury while

Henry was determined to keep it at Reading Abbey. Frederick was eventually

persuaded to drop the matter following the receipt of numerous gifts including

four great falcons and a magnificent campaigning tent that struck awe into its

beholders.

Old Age

In 1160

Matilda suffered a serious illness and her influence over Henry waned when she

advised against the appointment of Chancellor Thomas Becket as Archbishop of Canterbury[ix]. Matilda was involved in

attempts to mediate between Henry and his Chancellor Thomas Becket when the two

men fell out in the 1160s.

|

| Henry II and Beckett |

When the

Prior of Mont St Jacques asked Matilda for a private interview on Becket's

behalf to seek her views, she provided a moderate perspective on the problem

Matilda explained that she disagreed with Henry's attempts to codify English

customs, which Becket was opposed to. She also condemned poor administration in the English Church

and Becket's own headstrong behaviour.

Throughout

her retirement Matilda still

continued her role as peacemaker; as late as 1167 she was trying to de-escalate

the problems between her son and Louis VII, this time a quarrel over crusading

funds. A truce was agreed in August and Henry then launched on an invasion of

the Duchy of Brittany.

Weeks later

Henry was recalled by the death of his mother. Matilda died on 10th

September 1167 surrounded by monks from the monastery of Bec. She was buried in the

Abbey, in a service led by Rotrou, the Archbishop of Rouen. Whether she would have approved of

the inscription on her tomb is moot;

‘Great by birth, greater by

marriage, greatest in her offspring, here lies the daughter, wife and mother of

Henry.’[x]

Matilda left

the abbey the contents of her private chapel, having already donated much of

the treasure she had brought back from Germany.

Bibliography

The Feudal

Kingdom of England 1042-1216 – Frank Barlow, Pearson Education Ltd 1999

Gerald of

Wales – Robert Bartlett, Tempus Publishing Ltd 2006

Stephen and

Matilda – Jim Bradbury, The History Press 2005

She Wolves –

Helen Castor, Faber and Faber 2010

Early Medieval

England – MT Clanchy, Folio Society 1997

The

Plantagenets – Dan Jones, William Collins 2013

King Stephen

– Edmund King, Yale University Press 2010

Doomsday to

Magna Carta – AL Poole, Oxford University Press 1987

Early

Medieval England – Christopher Tyerman, Stackpole Books 1996

Henry II –

WL Warren, Yale University Press 2000

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

In 1158 a treaty between Henry and Louis agreed that Henry’s son Henry and

Louis’ daughter Margaret would marry and the Vexin would be her dowry

[ii]

It is equally likely that Henry had his eye on Eleanor’s vast inheritance. It

was alleged by Gerald

of Wales (a chronicler hostile to the Angevins) that Eleanor had an affair

with Geoffrey of Anjou

[iii]

Henry failed to gain Louis’ consent to the marriage, as by right he should have

done as one of Louis’ vassals

[iv]

King Stephen - King

[v]

Henry II - Warren

[vi]

She-Wolves - Castor

[viii]

She-Wolves - Castor

[ix]

Henry must later have rued the day that he did not follow his mother’s advice

[x]

She-Wolves - Castor

.jpg)