|

| Matilda (15th century) |

Of the

nobility there were only two defectors to Matilda; Brian Fitzcount[i] and Miles of Gloucester, an able

military tactician who was henceforth to keep Stephen’s forces running from one

castle under the threat of siege to another. Miles immediately launched an

attack on Stephen’s troops besieging Brian Fitzcount’s castle at Wallingford.

He broke the siege which freed Fitzcount to do his worst.

Miles then

appeared to have London in his sights. Stephen broke off his attack on Bristol;

William of Malmesbury wrote;

‘He [Stephen]also approached

Bristol, and going beyond it, burnt the neighbourhood around Dunstore, leaving

nothing, as far as he was able, which could minister food to his enemies, or

advantage to any one.’[ii]

Stephen

turned his army about to protect his capital. Miles then wrong-footed Stephen

by turning back and attacking Worcester, now the property of Waleran de Beaumont. Miles left the city

devastated.

|

| Ranulf de Gernons coat of arms |

Stephen’s

position was further weakened by his falling out with Ranulf de Gernons, Earl of Chester. Stephen failed to conciliate de

Gernons, preferring instead to promote the Beaumont twins who were vying with

de Gernons for control of much of the midlands. De Gernons also felt slighted

by the handing over of Carlisle castle[iii] to David of Scotland in the peace

that followed the second Scottish incursion. De Gernons’ wife was the daughter

of Robert of Gloucester, but her husband did not espouse Matilda’s cause.

A Sea Change

At the end

of the year Roger of Salisbury died of a quartan ague[iv]; it cannot have been long before

many of his countrymen wished they could join him.

‘The whole of this year [1140] was embittered by the horrors of war. There

were many castles throughout England, each defending their neighbourhood, but,

more properly speaking, laying it waste. The garrisons drove off from the

fields, both sheep and cattle, nor did they abstain either from churches or

church-yards.’[v]

This was a

harbinger for the years to come.

|

| East gate of Lincoln Castle |

Late in 1140

de Gernons seized the royal castle of Lincoln and Stephen realised that he needed to conciliate de Gernons.

Stephen allowed de Gernons extensive concessions to keep him onside. But a few

weeks later changed his mind and attacked de Gernons at his new Lincoln

stronghold.

De Gernons

called for help from his father-in-law who brought troops up, surrounding the besieging

army. The battle on 2nd February 1141 saw

Stephen taken captive; many of the nobility had deserted, but that did not mean

that they were keen for Matilda to take the throne. Negotiations for support

among the various stakeholders meant that Matilda’s coronation was delayed.

Stephen’s

wife Matilda of Boulogne called for her husband’s release.

She was supported by her brother-in-law, Henry of Winchester who saw a chance

to claw back power and position lost to the Beaumont twins.

A Rash and Proud Woman

Henry of

Winchester, as Papal Legate, summonsed a church council, demanding that the

prelates honour their original oaths of allegiance to Matilda and that they

join him in setting Stephen aside. Matilda of Boulogne sent an emissary of her

own asking for Stephen’s release and for his return to the throne. The king’s

supporters were excommunicated and Matilda of Boulogne’s plea ignored.

Matilda of

Boulogne was Countess of Boulogne in her own right and had access to

funds and men to keep control of her lands in Essex. In addition the captain of Stephen’s mercenaries, William of Ypres, stayed loyal to Stephen’s cause and held Kent with the assistance of more mercenaries paid for with money from

Boulogne.

Matilda

meanwhile was having problems gaining control of the capital. The Londoners’

sympathies were with Stephen and his wife. Until Matilda was able to persuade

them to change their loyalties it would be difficult, if not impossible, for

her to be crowned. The Londoners had sent representatives to the church council

with;

‘A request that their lord

the king should be released from captivity.’[vi]

Matilda took

a leaf out of Stephen’s book by buying support; she created a number of new

earldoms, making Geoffrey de Mandeville earl of Essex, giving him control over London and Middlesex as well. With Geoffrey de Mandeville’s help Matilda entered the city of

London in the summer of 1141.

But by now

her headstrong, overbearing and extremely tactless behaviour had alienated many

of the nobility and clergy. Matilda was even arrogant when dealing with her

close relations, her brother Robert and her uncle King David of Scotland.

Disaster

|

| Coat of arms of the Counts of Boulogne |

Henry of

Winchester’s rapprochement with Matilda was short-lived; she refused to assist

having the hereditary estates of Blois settled on Henry’s nephew Eustace[vii]. She also broke her undertaking to

take Henry’s advice on church affairs. In retaliation Henry of Winchester

ensured that

‘His complaints against the

empress were disseminated through England, that she wished to seize his person;

that she observed nothing which she had sworn to him; that all the barons of

England had performed their engagements towards her, but that she had violated

hers, as she knew not how to use her prosperity with moderation.’[viii];

In early

summer Matilda demanded an enormous sum of money from the city of London. The

Londoners then made a pact with Matilda of Boulogne after her men had run amok

in the capital. Matilda was forced to flee the city when she was set upon at a

banquet on 24th June by armed citizens. Matilda made for Winchester

to secure the treasury. She was followed by the news that Henry of Winchester

had returned to the fold at his sister-in-law’s urging.

Escaping Oxford

|

| Winchester Cathedral |

William of

Ypres moved his men down to Winchester with such speed that Matilda’s men were

taken by surprise and almost completely encircled. Robert of Gloucester fought

a delaying action to allow his half-sister to escape. He was then captured and

Matilda found herself forced to exchange Robert for Stephen.

Many of

Matilda’s wavering supporters had wavered back to Stephen’s side, while others

of her supporters had lost horse and armour in a desperate attempt to escape.

Robert of Gloucester travelled over to see Geoffrey of Anjou with pleas that he

come to his wife’s aid. Robert of Gloucester was met with the answer that

Geoffrey was too busy taking Normandy to worry about England. Instead, in

November 1142, he sent his 9 year old son as his proxy along with over 300

knights and 52 ships. The young Henry was to be the standard bearer of the

Angevin cause.

|

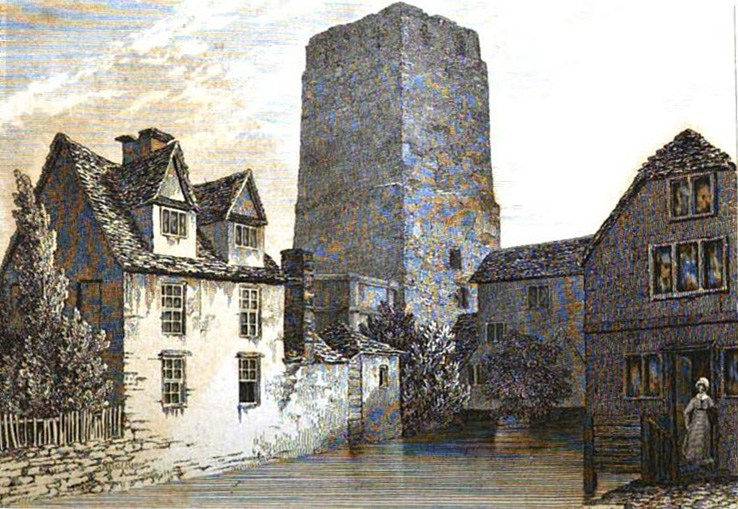

| Oxford Castle |

Henry’s

mother was besieged in Oxford Castle[ix] where she had taken refuge while her

champion was in Normandy. Matilda was able to free herself from captivity, crossing

the frozen River Thames and then walking through the snow

covered Oxfordshire countryside to reach the safety of Wallingford;

‘The empress, with only four soldiers, made her escape through a small

postern, and passed the river. Afterwards….she went to Abingdon on foot, and thence

reached Wallingford on horse-back…. the

soldiers who had remained at her departure, after delivering up the castle, had

gone away without molestation, and the holidays admonished them to repose

awhile, they resolved to abstain from battle, and retired to their homes.’[x]

Robert’s

troops enabled him to halt Stephen’s fresh offensive and gained control of key

fortresses in Dorset and Somerset. Robert seems to have decided over

the next few months to throw his weight behind putting young Henry on the

throne, rather than his discredited mother.

In the

aftermath of the retreat from Winchester, Matilda rebuilt her court at Devizes Castle, one of the properties formerly

belonging to Roger of Salisbury that had been confiscated by Stephen. Matilda

established her household knights on the surrounding estates, supported by

Flemish mercenaries, ruling through the network of local sheriffs and other

officials. Many of her supporters who had lost lands in the regions held by the

King travelled west to take up patronage from Matilda.

Bibliography

The Feudal

Kingdom of England 1042-1216 – Frank Barlow, Pearson Education Ltd 1999

Stephen and

Matilda – Jim Bradbury, The History Press 2005

She Wolves –

Helen Castor, Faber and Faber 2010

Early

Medieval England – MT Clanchy, Folio Society 1997

The

Plantagenets – Dan Jones, William Collins 2013

King Stephen

– Edmund King, Yale University Press 2010

Doomsday to

Magna Carta – AL Poole, Oxford University Press 1987

At the Edge

of the World – Simon Schama, BBC 2002

Early

Medieval England – Christopher Tyerman, Stackpole Books 1996

Henry II –

WL Warren, Yale University Press 2000

www.wikipedia.en

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.