|

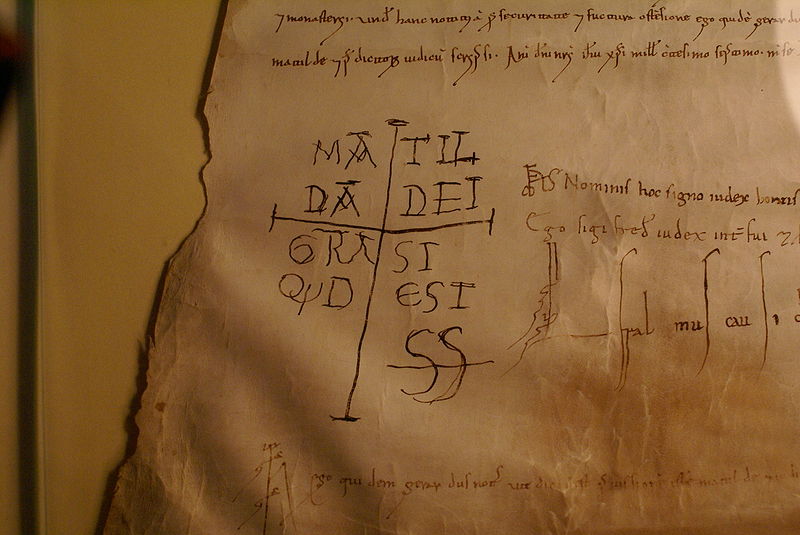

| Matilda's signature |

The Reformist Church

Matilda’s

objectives included the election of a reformist pope to replace Gregory and

closing the Alpine passes against further incursions from Germany. The

reformers inability to find a strong candidate to replace Gregory left them

dependent upon Matilda. There was fighting between the reformers and the

traditionalists in Rome; Bernold of Constance reported;

‘At this time much killing,

burning and pillaging was committed between the supporters of Henry and the

vassals of St Peter.’[i]

Matilda’s

triumph at Sorbara enabled her to successfully interfere in internal church

matters. Following the deaths of Henrician supporters within the church, along

with her allies Matilda organised the election of reformist clergy to the sees

of Modena. Reggio and Pistoia. By 1088 the Gregorian radical Bonizo[ii] was elected bishop of Piacenza with the support of the citizenry. Cremona also found itself with a Gregorian bishop when Walter was elected sometime

before September 1086.

|

| Bishop Diambert (2nd L) |

A number of

clergymen who had supported Henry now saw their way to the truth and light; Archbishop Anselm III of Milan and Bishop Diambert[iii] of Pisa started to modify their

antagonism around 1088. The struggles between the Gregorian reformers and the

traditionalists slowed down the pace of change but Matilda and her allies were

able to ‘strengthen and expand’ their

hold over much of the north and central Italy.

After his

death Gregory had recommended three candidates to succeed him; his first choice

was Anselm of Lucca who was dead by the time elections were held in May 1086

and another of Gregory’s choices, the Abbot of Montecassino was chosen in

Anselm’s place. A divisive figure, Pope Victor III survived in the hot house of

Rome for less than two years despite Matilda’s support. Victor was replaced on

12th March 1088 by Odo of Châtillon, Bishop of Ostia, and a committed reformer who took

the name Urban II.

Marriage Number Two

|

| Duke Welf of Bavaria |

Before

crossing the Alps Henry undertook a brief campaign to capture Matilda’s lands

in Lorraine. In 1090 Henry crossed the mountain

passes and engaged in reducing Matilda’s castles north of the Po,

while Matilda was entrenching down south of the river waiting for a chance to

counterattack. Bernold of Constance wrote;

|

| Welf and Matilda |

‘Duke Welf [the Younger] of

Italy incurred much arson and pillaging when King Henry entered Lombardy in

this year, but at the exhortation of his beloved wife. Lady Matilda, he fought

to remain in fidelity to Saint Peter, and to withstand Henry manfully.’[iv]

On 10th

April 1091 Henry’s troops took Mantua after a siege lasting nearly 12 months. Henry then concentrated his

efforts at subduing Matilda’s lands north of the Po, taking the castle of

Manerbio[v].

In the

winter of 1091-2 Matilda’s troops were defeated at the battle of Tricontai at

the hands of Henry’s troops. Welf, recently en-feoffed with the lands her

father had held from the Bishop of Mantua, was probably one of her commanders

at the battle. Matilda had sent a force over the Po to hunt for Henry. It has

been surmised that Matilda’s force were betrayed by Hugh of Maine, Welf’s uncle.

Not long

after their marriage Welf the younger discovered that Matilda had secretly

endowed the church with all her wealth and the couple separated in 1095. Welf

and his father then swapped sides and became allies of the emperor, possibly

hoping that Henry would confirm Welf as his father’s successor as Duke of Bavaria.

Against the Emperor

Despite the

defeats at Mantua and Tricontai Matilda fought on. Nevertheless Henry’s

position had improved; the reformers had lost ground in Germany where a number

of Gregorian churchmen had died along with the anti-Duke of Swabia, Berthold of Rheinfelden.

For his part

Urban was finding it difficult to impose his authority in Rome; the Henrician

Pope Wibert had not been expelled from the city until the summer of 1089; he

then set up shop in Ravenna. By February 1091 he was back inside the walls of

the Vatican while Urban celebrated Christmas outside the city walls. Henry held

court in Mantua over Christmas, staying there until Easter 1092.

| Carpineti |

In the June

Henry started a campaign against Matilda; seizing towns and fortresses

throughout the lands south of the Po. He took the castles Montemorello and

Montealfredo[vi]

and captured Matilda’s standard bearer Gerard. Henry then moved on to Monteveglio[vii], where his ambitions were stymied by

both the rugged mountains and the stubborn defence. Wibert arrived in late

summer with reinforcements.

In early

autumn Henry decided to attempt to end the status quo by offering to return to

Matilda all her lands and raise the siege at Monteveglio if she would recognise

Wibert as pope. Matilda held a conclave at Carpineti to consider the proposal, which she herself did not wish to accept. Many

of Matilda’s supporters, including Bishop Heribert of Reggio, were weary of the

seemingly endless war with the emperor. Despite this the council eventually

agreed to refuse Henry’s offer.

Another Humiliation At Canossa

Henry now

decided to make another attempt to take Canossa to where Matilda had just

returned. Matilda divided her forces, leaving some of her soldiers to defend

the fortress at Canossa and took the remainder to her fortress at Bianello. It

is likely that Henry was able to field a much larger force than the one that

Matilda had to protect her demesnes.

Henry’s

forces made an unsuccessful attack on Canossa and then regrouped, having lost

the imperial banner. Donizo[viii] wrote;

Having a heart dejected

beyond measure, because he saw that the moment had turned against him.

He did not want to ride that

road, nor even to know if [sic] it,

Not for ten thousand pounds!

The loss of the banner

marked his defeat.

So that henceforth his reputation for losing soldiers

grew.’[ix]

Henry had

hoped to take Matilda prisoner, thus removing his major antagonist. But

continuing his attacks on Canossa left his supply lines open to attack from

Bianello. For her part Matilda was aware of the need to stay out of Henry’s

hands.

Henry’s

decision to retreat was undoubtedly correct from a military viewpoint, but it

did almost irreparable damage to his reputation and from now on Henry’s forces

were to suffer, particularly after Henry left them to their own devices. Matilda

took advantage and over the next few years was able to win back most of the

lands taken from her.

Rebellion

In 1093 Henry

was further humiliated by the transfer of his son Conrad’s allegiance to the reforming arm of the church. Henry was

convinced that Matilda was the cause of Conrad’s conversion. The author of

Henry’s Life wrote;

‘[Conrad] was won over by

the persuasions of Matilda – for whom may not womanly guile corrupt or deceive?

– and joined his father’s enemies.’

|

| Cathedral at Borgo San Donnino |

Henry

imprisoned Conrad who managed to escape and in July Matilda and her allies

elected him King of Italy[x] and she arranged his coronation in

Milan by Archbishop Anselm. Conrad took up residence in Borgo San Donnino[xi], impeding imperial access to Rome.

Conrad was not alone in his conversion; a number of Henry’s other nobles

followed him into the reformists’ fold.

In 1094

Henry’s wife, Eupraxia of Kiev[xii], left her husband and, like her

stepson, looked to Matilda for her protection. The Annales Stadenses claims that;

‘The queen finally escaped

her guard, came into Italy to that very powerful Matilda and by her escort to

Pope Urban, to whom she sadly related her misfortune.’[xiii]

In March

1095 at the Council of Piacenza, Eupraxia claimed that Henry had

imprisoned her in Verona and had forced her to have sexual intercourse with

other men. Donizo alleged that Matilda sent the men who helped Eupraxia escape

her imprisonment in Verona.

These

personal setbacks and the military missteps after Canossa led to a collapse of

Henry’s authority south of the Alps. Matilda and her allies held all the major

passes across the Alps and Henry was unable to take back control of his lands

in Italy.

Bibliography

The Making

of Europe – Robert Bartlett, Penguin Books 1994

The Military

Leadership of Matilda of Canossa – David J Hay, Manchester University Press

2008

The Holy

Roman Empire – Friedrich Heer, Phoenix Giant Paperback 1995

The Oxford

History of Medieval Europe – George Holmes, Oxford University Press, 2001

Absolute

Monarchs – John Julius Norwich, Random House 2011

The First

Crusade – Steven Runciman, Folio Society 2002

The

Hapsburgs – Andrew Wheatcroft, Folio Society 2004

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

The Military Leadership of Matilda of Canossa - Hay

[ii]

Later made a saint; mutilated and expelled from the city in 1089

[iii]

Or Dagobert

[iv]

The Military Leadership of Matilda of Canossa - Hay

[v]

Between Brescia and Cremona

[vi]

Both castles apparently lying in the mountains to the south of the Via Emilia

[viii]

Author of an epic poem starring Matilda

[ix]

The Military Leadership of Matilda of Canossa - Hay

[x]

Henry later deposed Conrad and had his younger brother Henry elected in his

place, making Conrad more dependent on Matilda

[xi]

Now Fidenza

[xii]

Also known as Adelaide; she was the daughter of Prince Vsevelod of Kiev

and the widow of one of Henry’s nobles

[xiii]

The Military Leadership of Matilda of Canossa - Hay

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.