|

| Henry Howard |

Henry blamed

the Seymours for his cousin’s downfall and early in 1542 wrote a

vitriolic allegorical poem directed at Anne Seymour, Edward’s

second wife, who may have snubbed Henry when he asked her to dance. It was also

a hit at the new men at court and makes reference to the brave Howard clan,

many of whom were still locked up the Tower. The poem made specific reference

to Henry’s uncle Thomas who died in the Tower for love of Margaret Lennox.

Henry has

been credited with bringing the Renaissance style of poetry to England,

introducing the sonnet form. Poetry was an acceptable

pastime at the Tudor court and courtiers were expected to have some skills in

writing ballads and poems. Henry used allegory to complain about what he saw as

the injustices of life. Often these injustices were matters that Henry brought

on his own head by his ‘foolish pride’

and arrogance.

Henry had

lived his life weighed down by the expectations of others, in particular his

father who had very rigid expectations of how the future fourth duke of Norfolk

should behave. In his poetry Henry was able to represent himself as a noble and

isolated hero of his dreams. It was this façade that he presented to his fellow

nobles,

‘That then stir up the

torment of my breast

To curse each star as causer of my fate.

And when the sun hath eked the dark represt

And bought the day, it doth

nothing abate

The travail of my endless smart and pain.’[i]

When Sir

Thomas Wyatt died not long after Catherine Howard’s execution Henry wrote an

elegy in heroic quatrains to his friend and fellow poet. Wyatt’s poetry was

less explosive than Henry’s; Henry wrote with a disregard for the consequences,

much as he lived his life. Henry was a man out of place in the Tudor court

where one mishap could end you up on the block.

Wyatt and

Henry translated Petrarch’s sonnets. Henry also translated Virgil’s second and fourth books of the Aeneid into blank verse in rhyming meter and it is believed that he was the first

English poet to do use the form.

Fighting Up North

|

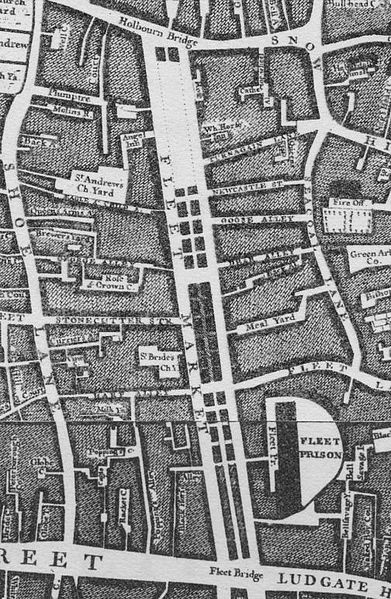

| The Fleet |

July 1542

saw Henry in the Fleet for quarrelling with one Jhon a Legh[ii];

it is possible that Henry assaulted the victim or challenged him to a duel[iii].

Henry immediately sent his servant to demand of the council that he be released

with immediate effect. In early August Henry was released on his own

recognisance of ten thousand marks[iv].

The

following month saw Henry on the road to Scotland to fight incursions from

Scottish raiders, owing allegiance to King James V, Henry VIII’s nephew. Henry VIII

declared war on the Scots, knowing that their French allies were embroiled on

the continent fighting Charles V. The Duke of Norfolk was made Lieutenant

General of the army and Henry travelled in his father’s wake.

The English

army of 20,000 crossed the border at Berwick on Tweed on 21st October with orders from the king to

perform ‘some notable exploit’. The

appalling weather forced the army back into England having done little more

than sack Kelso Abbey and the nearby town. The king was not amused writing to

Norfolk about;

‘The loss of this enterprise

[which was] not of such sort as we did trust and desired.’[v]

But the

king’s amour propre was soothed when Sir Thomas Wharton[vi] won the Battle of Solway Moss in November[vii].

The Howards and their men were not involved in the fighting and Henry returned

to London more restless than ever, his aggression un-blunted by what little

action he had been caught up in.

Fighting at Home and Abroad

|

| Arms of Sir John Wallop |

Back from

Scotland found Henry setting up home in London, but he quartered himself in Cheapside and a number of his servants and braggarts ran amok. His father’s

connections got him off the charges only for Henry to fall foul of Bishop Gardiner’s

fasting laws. In April 1543 he was interrogated by four privy councillors who

were sympathetic but Surrey found himself back in the Fleet. Once again he took

up his pen to rage against unkind fate.

Henry was

out of prison by May 1543[viii]

and back at court in time to see Henry VIII sign a peace treaty with the Holy

Roman Emperor. The two powers planned a joint invasion of France. Sir John Wallop led the English force across the Channel and Henry begged

the king for permission to march with them.

Henry

arrived at the English camp outside Landrecy in October 1543. Henry immediately set about orientating himself to the

approbation of Sir John who wrote an approving letter back home. The siege of

Landrecy was lifted by the arrival of François with an army which camped at Cateau-Cambrésis. The English were lured away from Landrecy which

François immediately re-victualised before decamping with his army. Henry

returned home.

Henry was

back in France the following year with another invasion force; Norfolk was

Captain of the Vanguard and his son and heir was Marshall of the Field. The

weather conspired against the English who planned to besiege Montreuil. The choice of town was not a happy

one and both Norfolk and the imperial generals inveighed against going ahead; but

from far away in England Henry VIII overruled them.

The armies

were subjected to a series of attacks by the French which reduced their

effectiveness, especially when Henry VIII changed his mind and insisted that

the priority was Boulogne. The king actually crossed the channel to impose his

priorities upon the joint armies and Henry and his uncle William were present

when Boulogne surrendered to Henry VIII.

|

| Ramparts of Montreuil |

It was too late

for the army at Montreuil; the French Dauphin Henri came to the town’s relief

and on 28th September 1544 the English decamped. Henry, as Marshall

of the Field, was responsible for the army’s evacuation. They arrived at

Boulogne relatively safe and sound on 30th September thanks to

Henry’s masterminding of the evacuation.

In April

1544 there were rumours that François intended to regain Boulogne and invade

England with an army of 40,000 men. Henry was appointed responsible for the defence

of the town. And on 3rd September 1545, after a series of deaths among senior

military men, Henry was made Lieutenant General of the King on Sea and Land for

all English continental possessions. Norfolk wrote to Henry advising him not to

encourage Henry VIII’s desire to permanently extend the Pale of Calais;

‘Have yourself in await,

that ye animate not the King too much for the keeping of Boulogne, for whoso

doth, at length shall get small thank. I have so handled the matter, that if

any adventure be given to win the new fortress at Boulogne, ye shall have

charge thereof.’[ix]

Henry

ignored the warning, as he did all good advice. But eventually the cost of

holding Boulogne meant that even the king came to his senses and ordered the

evacuation of the town. Henry returned to England.

Proud Foolish Boy

|

| Tower of London |

Henry Howard

has been described as;

‘An extravagant roistering

soldier-poet….a brilliant, indiscreet young man who loved to flout conventions

both trivial and important, ostentatiously refusing to eat meat in Lent,

complaining openly about the power given to low-born men like Wolsey and

Cromwell and, worse, boasting about his own descent from the Plantagenets.’[x]

It was this

arrogance which was to bring Surrey and his father to the Tower. The two Seymour brothers, Edward in particular, were

looking forward to a long period of power during their nephew’s minority and

the Howards were an irritant in their rosy vision of the future.

On 12th

December 1546 both Surrey and his father were arrested and taken to the Tower.

A plot had been uncovered; at Surrey’s instigation his sister Mary was to

romance the king;

|

| St Michael's Framlingham |

Upon being

questioned Mary incriminated both her brother and her father[xii].

Henry VIII was more than happy to rid himself of the Howard family and their pleas

for mercy were ignored. To compound his arrogance Surrey had quartered his arms

with those of Edward the Confessor. Edward Seymour and John Dudley, Viscount Lisle were more than happy to use the plot and Surrey’s arrogance

to topple their rival Norfolk

On 7th

January Parliament passed an act of Attainder against both Surrey and Norfolk.

Surrey was tried at the Guildhall on 13th, found guilty and

condemned to death. Surrey was executed on 19th January 1547[xiii]

and was buried at the church of St Michael the Archangel, in Framlingham. Norfolk’s writ of execution was

signed by the king on 27th January. Norfolk’s execution was set for

the following morning but it was Henry who was to die instead.

Bibliography

Thomas Wyatt

– Susan Brigden, Faber and Faber 2012

Henry VIII’s

Last Victim – Jessie Childs, Vintage Books 2008

The Ebbs and

Flows of Fortune – David M Head, University of Georgia Press 2009

House of

Treason – Robert Hutchinson, Phoenix 2009

Henry VIII –

Robert Lacey, Weidenfeld & Nicholson & Book Club Associates 1972

The Earlier

Tudors – J D Mackie, Oxford University Press 1992

Rivals in

Power – David Starkey, MacMillan London Ltd 1990

The Six

Wives of Henry VIII – Alison Weir, Pimlico 1992

The Lost

Tudor Princess – Alison Weir, Vintage 2015

A Tudor

Tragedy – Neville Williams, Barrie & Jenkins 1964

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

Henry VIII’s Last Victim - Childs

[ii]

Possibly John Leigh of Stockwell, Queen Catherine’s half-brother

[iii]

Illegal within the confines of the court

[iv]

In 2015 the relative: historic standard of

living

value of that income or wealth is £5,559,000.00 labour earnings of that income or wealth is

£54,490,000.00 economic status value of that income or wealth is £194,100,000.00 economic power value of that income or

wealth is £2,427,000,000.00 www.meeasuringworth.com

[v]

Henry VIII’s Last Victim - Childs

[vii]

James V died within the month to be succeeded by his newly born daughter Mary, Queen of Scots

who was to embroil Henry’s son Thomas in her web of deceit – see http://wolfgang20.blogspot.co.uk/2013/10/a-fatal-lust-for-power-iv.html

and http://wolfgang20.blogspot.co.uk/2013/10/a-fatal-lust-for-power-v.html

[ix]

Rivals in Power - Starkey

[x]

Henry VIII - Lacey

[xi]

The Six Wives of Henry VIII - Weir

[xii]

It is believed that Mary was angry that neither father nor brother had helped

in her fight for some of her dower from Fitzroy; she was poor and reduced to

living in her father’s home, with only her title as a remnant of her marriage

[xiii]

The last person to be executed in Henry’s reign

interesting that he introduced blank verse, paving the way for Shakespeare and others. Arden of Faversham is based on a true story, somewhat sexed up and glossing over the fact that the yclept Arden was a miser and a wife beater.

ReplyDelete