|

| The Burghers of Ghent surrender to Philip the Good |

Ghent Humbled

Needing

funds to continue his war Philip dropped his prohibition on the transport of

English cloth. By this point Isabella had decided to support the Duke of York[i], who was pro-trade with

Burgundy, in the internecine war in the English court. She now prepared to

travel to Gravelines. Charles VII became aware of her intentions which would

interfere with the final stages of the Hundred Years War; Charles was hopeful

of throwing the English out of his country for good[ii].

Ghent

finally surrendered to her lord after the Battle of Gavère on 23rd July 1453 where 17,000 Ghentish

men died. The Burgundians had rallied behind Philip in his fight with the men

of Ghent.

‘And their dead were

estimated at seventeen or eighteen thousand men, both killed and drowned. Among

others several of their captains and deans were killed, including a good ten or

eleven of their echevins. Besides this, a number of prisoners were taken.’[iii]

During July

1453 Henry VI lost his hold on reality for the first time; Queen Margaret

managed to keep the matter hidden for three months until the birth of her son Edward of Westminster in October. Richard of York was the

logical choice to become protector of the realm in the king’s stead and he had

Suffolk arrested and replaced him as Captain of Calais with Richard Neville[iv], Earl of Warwick. The war in France was coming to a stuttering close; after

the fall of Châtillon[v] in July there was little

left save the Pale of Calais to fight over.

A New Wife for Charles

|

| Pope Nicholas V |

Charles VII

was now looking to his investigation into the legality of Joan of Arc’s trial

to yield dividends; the case was going to Rome and Charles anticipated that he

would be given sovereignty over all of Burgundy. He hoped to go down in history

as the king who reunited France.

In his turn

Philip was looking to join the Pope Nicholas V’s call for a crusade against the Ottomans following the fall of Constantinople[vi]. Philip spent much of the early part

of 1454 celebrating his victory over the men of Ghent and working to forge his

men into a fighting unit that would win him renown in the east. Isabella

supported Philip in this ambition.

While Philip

was planning a French bride for Charles, now 21, to consolidate any alliance he

might be able to make with Charles VII, Isabella had her eye on one of the Duke

of York’s younger daughters for her son. To that end she started negotiations

with the duke, now Regent[vii].

Sadly for

Isabella her plans came to naught as Philip put his foot down; he decided that

the potential for peace with France would be best served if Charles was to

marry his cousin[viii]

Isabella of Bourbon, daughter of Charles I, Duke of Bourbon. Neither Charles nor his mother wanted the match which

Philip insisted on. The young Isabella had been living in Isabella’s household;

she was favoured by Philip who was fond of his sister’s child.

Philip

obtained a release from the pope for the marriage between first cousins even as

he started fund-raising for the crusade. He also decided to attend the Imperial Diet at Regensburg to that end. He made Charles;

Governor and Lieutenant

General , in the absence of my most redoubted lord and father, of his lands and

lordships in the Netherlands.’[ix]

in his

absence. Philip also issued edicts on expenditure that curbed the magnificence

of his court, although he prudently allowed sufficient monies to overawe the

German princes at the Diet. Feasts, games, jousts and concerts were severely

curtailed and the pensions of court officials reduced.

The Heir’s Second Wife

|

| Charles and Isabella of Bourbon |

Philip

suddenly discovered Isabella’s plans to marry their son to a member of the

English royal family. He was probably apprised of Isabella’s manoeuvrings by

one of the de Croy brothers[x]. Concerned that Isabella

would have her own way while he was at Regensburg Philip pushed through the

betrothal without the approval of Isabella of Bourbon’s parents and that of

Charles VII.

At home

Isabella had spent the winter at La Motte-au-Bois[xi] before returning to the Rihour

Palace in Lille[xii]

in the spring. Her representatives had been meeting with the English since

January. Charles joined his mother in Lille in early May. Not long after Philip

left Salins for Nevers where he met his sister, the Duke of

Orléans and Pierre Amboise the representative of the Duke of Bourbon[xiii]. Philip’s demands for

the seigneury and lands of Chinon to be given to Isabella of Bourbon

were rejected during several weeks of negotiations[xiv].

Unable to

come to an agreement Philip left Nevers for Dijon, prepared to wait until his

demands were met. He stayed there throughout August and September. In the north

Isabella was struggling to keep the Anglo-Burgundian talks alive. More and more

Burgundian ships were being taken by the English and in August both Charles and

Isabella wrote to Philip warning of a possible English attack. They wrote again

in September.

|

| Termonde |

By October

Charles VII was becoming worried that Isabella might prevail upon Philip to

accede to the English marriage she was chasing and wrote to Philip explaining

that he was unable to allow Chinon to be incorporated in the marriage contract;

‘So pray do not postpone the

marriage….for any cause, if by permission of the church and or our Holy Father

it can be lawfully completed.’[xv]

Philip

ordered Charles to marry Isabella of Bourbon straight away under the original

terms of the marriage contract signed by the Duke of Bourbon the previous year,

which included the lands of Chinon. The marriage took place as ordered on 31st

October 1454. Isabella was so chagrined that she failed to pay due deference to

her new daughter-in-law. Charles returned to his position as temporary governor

based at Termonde[xvi] while Isabella of Bourbon stayed

with her mother-in-law.

Drifting Apart

|

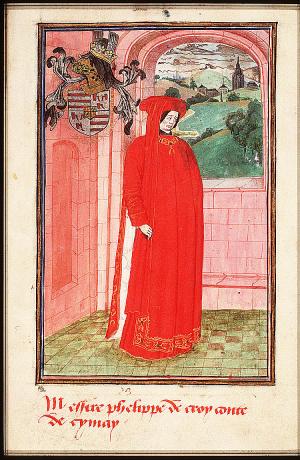

| Philippe of Renty |

The marriage

did nothing to repair the problems with France; the raids on Burgundy’s

northern borders continued and Charles VII refused to allow Philip to recruit

crusaders in France. In addition Isabella’s power was waning as that of the de

Croy family increased. As chamberlain Antoine was the most influential at

court, even more so than Chancellor Rolin, but his brother Jehan[xvii] and their sons Philippe of Renty and Philippe of Sempy also benefitted not only from Philip’s largesse but also from the hand

of Charles VII. They were powers in their own rights[xviii].

The de Croy

family were able to keep Philip focussed on France as Burgundy’s partner,

despite the depredations that France’s soldiers were making on Burgundian

lands, despite the French enclaves set up thereon. Philip’s blindness to French

intent is remarkable as are his ignoring of Isabella’s advice.

Philip, now

59, had taken his eye off the ball. He was distracted by his plans to go on

crusade and he still hoped to gain recognition for his imperial holdings. The de Croy family

meanwhile were looking forward to a French victory over Burgundy after which

they would reap their just rewards for supporting the victor. They increased

their involvement with the French even as Philip’s trust in Isabella decreased.

He now had no-one to counter the de Croy influence.

|

| Philippe of Sempy |

The

Burgundian coasts were plagued by French pirates who preyed mainly on English

shipping. The trade treaty that Isabella had stitched together with such care

was falling apart. The Burgundians did not help matters by holding up Staple

merchant caravans as they crossed Burgundian territory. Philip refused to send

Isabella to smooth matters over as she had done in the past.

The couple

were divided physically as well as mentally; Isabella was staying at Cassel. Isabella wanted to free her son from the de Croy influence. Charles was

very vocal in his opposition to his father’s policies and the two men argued a

lot throughout the winter of 1455-6. Charles was described as;

‘Hot-blooded, active and

irritable and, as a child, wanted his own way and disliked rebuke.

Nevertheless, he had such good understanding he resisted his natural tendencies

and, as a youth, there was no one more polite and well-tempered.’[xix]

In this

Charles was like his father; Philip was normally the most polite and courteous

to all, unless he was crossed and this rarely happened to him.

Bibliography

The Hundred

Years War – Alfred Burne, Folio Society 2005

The Reign of

Henry VI – RA Griffiths, Sutton Publishing Ltd 1998

The

Fifteenth Century – EF Jacob, Oxford University Press 1997

Margaret of

Anjou – Helen E Maurer, Boydell Press 2003

Isabel of

Burgundy – Aline S Taylor, Madison Books 2001

Philip the

Good – Richard Vaughan, Boydell Press 2014

Charles the

Bold – Richard Vaughan, Boydell Press 2002

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

Queen Margaret was now voicing her suspicions of her husband’s uncle openly

[ii]

Bar the area around the Pale of Calais

[iii]

Philip the Good - Vaughan

[iv]

Known as the Kingmaker

[vi]

Under the leadership of Mehmed II see http://wolfgang20.blogspot.co.uk/2014/10/mehmet-conqueror-iv.html

[vii]

Margaret had demanded the regency for herself, but too many of the nobility

viewed her as siding with Charles VII

[ix]

Philip the Good - Vaughan

[x]

Both highly influential with Philip

[xii]

A town of some 25,000 inhabitants

[xv]

Isabel of Burgundy - Taylor

[xvi]

Known as Dendermonde

[xvii]

Who fielded his own army independent of Philip’s

[xix]

Philip the Good - Vaughan

there aren't many people who can make me turn to a dictionary, echevins was a new one for me.

ReplyDeleteDynastic marriage is a recipe for personal disaster; maybe some of these despots would have been less martial if they had married for love and stayed at home happily rogering their wives and enjoying their children. Interesting that marriage to first cousins was illegal then without a dispensation, consanguinity laws for a good reason, I suppose, as royal intermarriages got more and more incestuous to seal deals.