|

| Henri II |

Fighting the Imperials

With the

salt tax revolt under control Henri could finally turn his attention to Charles

V. Early in 1550 the German Protestants, led by Maurice of Saxony, began talks which two years later

resulted in the Treaty of Chambord, a union between German Protestants and French Catholics

against the imperium. As his reward for subsidising the Protestant princes[i]

Henri was to occupy Metz, Cambrai, Toul and Verdun as Imperial Vicar.

Encouraged

by Diane and the Guise family[ii],

Henri saw this as the beginning of another French bid for the imperial crown

for himself. Within months many of the princes came to terms with their emperor

and switched sides. Action seemed necessary when imperial troops occupied a

strategic position near Metz[iii];

Montmorency organised the army of 50,000 that gathered in Champagne, with reserve forces held in

Picardy.

|

| Christina of Denmark |

Henri

declared war on 15th February 1552 and the French army swept into

imperial territories after Henri reviewed the troops at Joinville[iv] at the end of March. Montmorency and

François de Guise took Gorze after a short siege and Montmorency

walked into Metz on 10th April without a fight. Sometime in April

1552 Henri raised the status of Joinville into a principality in France,

changing the status of the Guise family into French nobility rather than noble

foreigners.

On the 14th

the French army violated the neutrality of Lorraine and marched on Nancy where Cardinal Lorraine had prepared the way. Christina of Denmark was removed as regent. Henri was

made Protector of the young Duke Charles[v] and the Lorraine nobility swore

their allegiance to the new Protector. French soldiers were garrisoned in the

main towns of the duchy. In May 1552 Henri wrote to Diane;

‘I find myself marching to

pass the river

Sarre….I beg you to believe that my army is splendid, and

animated by an excellent spirit; and I am confident that, if it is intended to

dispute the passage, Our Lord will aid me by His grace, as he did at first.’[vi]

The Counter-Attack

|

| Duke of Alva |

The emperor,

despite his infirmities[vii],

was determined to avenge this defeat and regain control of this stretch of land

that allowed communication between his northern and southern parts of his

empire. He gathered his allies for a counter attack. The imperial general the Duke of Alva arrived to take control of the army;

although it was late in the season Charles was determined to press on. 80,000

imperial troops marched into Lorraine in October. The weather was bad and the

army did not arrive before Metz until 14th.

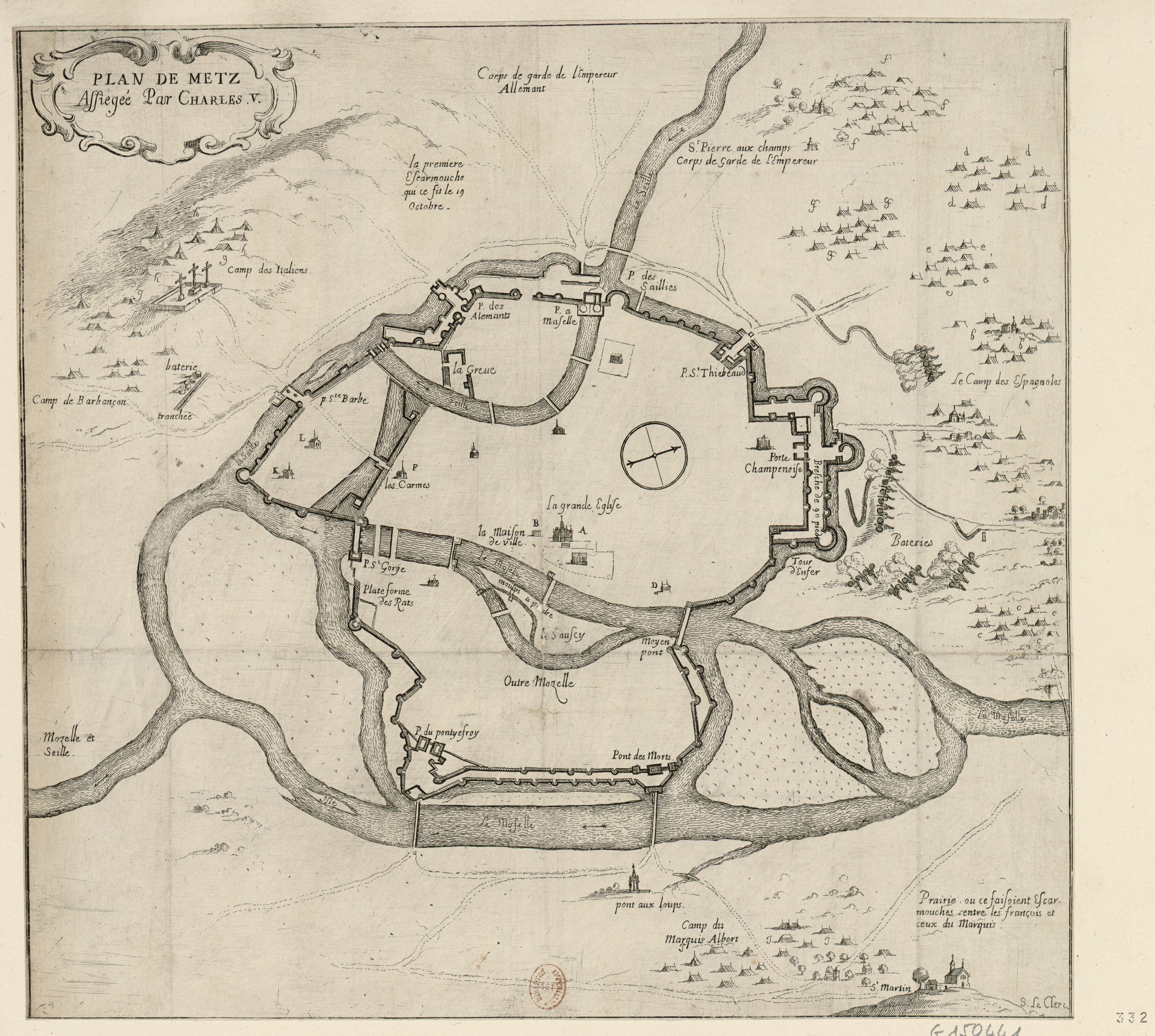

François de

Guise had only 6,000 men with which to defend the city against a siege, but had used the time available to

him to strengthen its defences. Metz was well supplied and the troops had

followed a scorched earth policy in the surrounding countryside. François kept

the citizens onside with personal appearances day and night and on occasion

using a spade himself to help prepare the fortifications, which involved

destroying the suburbs to give clear lines of fire.

The scions

of France’s greatest nobility came rushing to Metz to help defend the city; the

Prince de Condé, the younger brothers of the King of

Navarre, Charles de Bourbon-Montpensier, Montmorency’s sons and François de

Guise’ younger brothers all took positions defending the city walls.

|

| Plan of Metz |

By 18th

December François calculated that the imperial army had let off 11,800

cannonballs against the city. The cannonade failed to make much impression on a

city that was well-stocked to withstand the siege. It was the besiegers who

were suffering and eventually Charles raised the siege on New Year’s Day and

departed for Brussels, his tail between his legs.

He left

behind the corpses of over 12,000 men who had died from hunger, typhus and

scurvy. Also left behind were the sick and wounded; these men were given succour

by the French. To celebrate the victory François, good fanatical Catholic that

he was, had all the Lutheran books in the city burnt in a bonfire of books. The

Mantuan ambassador wrote;

‘There was no one among

those who were at Metz who does not praise the courtesy and good government of

Monsieur de Guise so that he is adored today by the whole kingdom.’[viii]

On 20th

February 1553 Henri publicly praised François in a full session of the Paris Parlement, the result of which was to make Montmorency jealous. This jealousy was

to burgeon into a hatred that was to poison the relationship between the houses

of Guise and Montmorency for the next decade.

The King’s Children

|

| Lady Janet Fleming |

In February

1549 the queen gave birth to Louis de Valois. And little over sixteen months later Charles de Valois was born on 27th June 1550.

Louis died on 24th October 1550. Diane de Poitiers was getting old

and, allegedly, had never been that interested in the sexual side of the

relationship, unlike Henri who had several other mistresses, three of whom bore

children from the unions.

Reports were

sent to Diane that Montmorency was bedding the future Dauphine’s governess, one

Lady Janet Fleming[ix]. In an attempt to overset the

Constable’s influence with the king Diane instructed François de Guise and his

brother to interrupt the couple en flagrante. To their consternation the de

Guise brothers found that Lady Fleming’s lover was none other than Henri.

Diane was

furious and confronted Henri who was chastened by the encounter; henceforth

Diane was to ally herself with the Guise family against the Montmorency faction

at court[x].

Lorenzo Contarini, the Venetian ambassador wrote home;

‘There was a moment when the

court asked itself which of the two the King loved the most – the Constable or

Madame de Valentinois – but now it is known, by many signs, that Madame is the

best beloved.’[xi]

Nevertheless

the liaison with Lady Fleming continued unabated until the lady became

pregnant, an event she announced to the court with great sangfroid.

‘God be thanked. I am with

child by the King, and I feel very honoured and very happy about it.’[xii]

|

| Prince Louis and the Princesses Jeanne and Victoire from Catherine de Medici's book of hours |

The result

was that Catherine and Diane united against the bold-faced intruder and Henri’s

life was made miserable until he sent Lady Fleming away from court. Lady

Fleming gave birth to Henri d’Angoulême[xiii] in Aix la Chapelle in 1551[xiv].

Diane

steered her lover back into his wife’s bed and the results were prodigious. On

19th September 1551 Catherine gave birth to Henri de Valois. There was then a break of nearly

twenty months before Marguerite de Valois was born on 14th May 1553. Hercule de Valois was born on 18th March 1555.

The couple’s final children, Jeanne and Victoire were born on 24th June 1556. Jeanne died the same day and

Victoire only lived until 17th August.

Catherine

must have been physically exhausted with the effort of producing ten children

in twelve years. That she lived was a testament to her own strength; indeed she

was to outlive all but two of her children[xv].

Bibliography

Martyrs and

Murderers – Stuart Carroll, Oxford University Press 2009

Catherine de

Medici – Leonie Frieda, a Phoenix Paperback 2003

Charles V –

Harald Kleinschmidt, Sutton Publishing 2004

French

Renaissance Monarchy – RJ Knecht, Longman Group 1996

The Rise and

Fall of Renaissance France – RJ Knecht, Fontana Press 1996

Catherine

de’ Medici – RJ Knecht, Pearson Education Ltd 1998

A History of

France – David Potter, The MacMillan Press 1995

Emperor

Charles V – James D Tracey, Cambridge University Press 2010

Henri II – H

Noel Williams, Methuen and Co 1910 (reprint 2016)

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

A lump sum of 240,000 éçus; in 2015 the relative: labour cost of that project is

£997,700,000.00 economic cost of that project is £39,300,000,000.00, www.measuringworth.com. This was to be

followed by monthly payments of 60,000 éçus

for upkeep of the Protestant armies;

[ii]

The Guise family were a cadet branch of the Lorraine family whose duchy had

fallen under the imperial sphere of influence

[iii]

Which controlled the lands between the Spanish Netherlands and Germany

[iv]

A Guise estate; the original castle was torn down during the revolution but the

Chateau du

Grand Jardin built by Cardinal Lorraine still stands

[v]

Charles was married to Princess Claude in January 1559

[vi]

Henri II - Williams

[viii]

The Rise and Fall of Renaissance France - Knecht

[x]

Montmorency had eased Henri’s way into Lady Fleming’s bed

[xi]

Henri II - Williams

[xii]

Catherine de Medici - Frieda

[xiv]

In 1557 Henri had a child by Nicole de Savigny a married woman; the boy was

named Henri de St-Rémy and was

made Count of St-Rémy although

he was not legitimated

[xv]

One of whom, Henri, was to die seven months after his mother. The other,

Marguerite the only one of her children who inherited Catherine’s good health,

died in March 1615

A very messy period, politically, and nervous religiously

ReplyDelete