|

| Dorothea dances at Almack's |

Patroness of Almack’s

In Regency times to have the entrée to Almack’s Assembly Rooms[i] was the highest a young

lady could aspire to. By 1814 Dorothea was one of the select Lady Patronesses

who decided to whom to award vouchers to. The vouchers cost ten guineas per

annum[ii]. The club was known as

the marriage mart to the irreverent.

Every Wednesday evening in the club’s Blue Room the six or

seven patronesses met to decide the fate of those wishing to attend the balls

held weekly at the King Street[iii] premises. They also

decided the fate of those considered of déclassé behaviour. Contrarily Lady Caroline Lamb

was allowed to attend despite her scandalous affair with Lord Byron solely because

she was the sister-in-law of Lady Cowper.

|

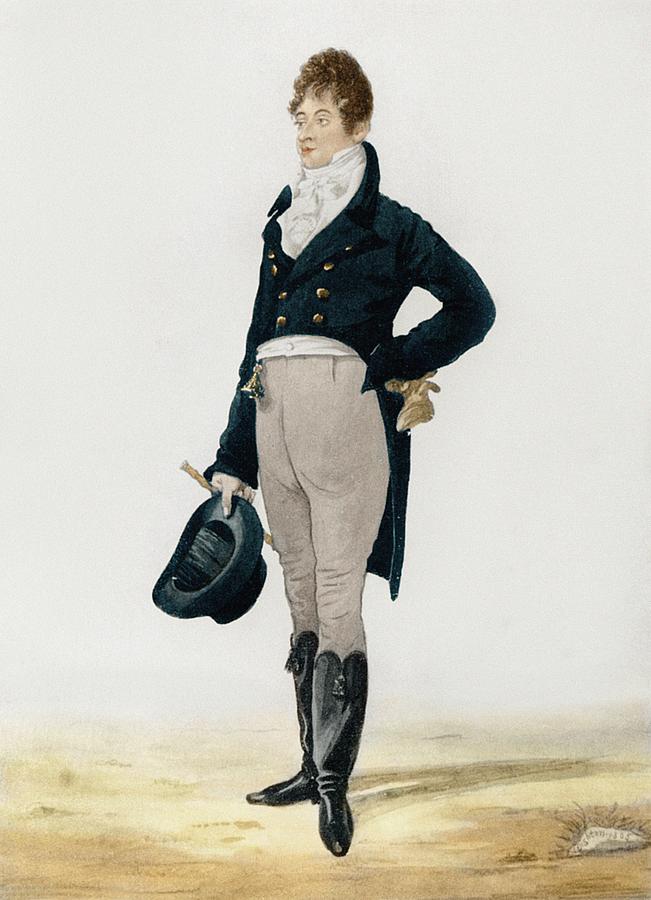

| Beau Brummell |

The Patronesses grew to rely on the advice on Beau Brummell, friend of

the Prince Regent, as to the suitability of gentlemen attendees. Brummell

wielded power as one of the arbiters whose nod was necessary to gain entrance

to Almack’s. The constant vigilance of the Patronesses, aided by Brummell, and

their exclusivity kept society under their thrall.

‘The most popular amongst these grandes dames was unquestionably Lady Cowper….Lady

Jersey's bearing, on the contrary, was that of a theatrical tragedy queen; and

whilst attempting the sublime, she frequently made herself simply ridiculous,

being inconceivably rude, and in her manner often ill-bred. Lady Sefton[v]

was kind and amiable, Madame de Lieven haughty and exclusive, Princess

Esterhazy was a bon enfant, Lady Castlereagh and Mrs. Burrell[vi]

de tres grandes dames.’[vii]

Dorothea was credited with introducing the waltz to Almack’s

in the spring of 1816, dancing with Lord

Palmerston, an acknowledged ladies’ man. The club took pains not to

resemble expensive private balls by avoiding sumptuous repasts. The

refreshments in the supper rooms consisted of thinly-sliced bread with fresh

butter and dry cake. To avoid drunkenness, only tea and lemonade were served in

the supper rooms. Despite the paucity of the food and drink the club was

extremely popular.

Social Success

|

| Comtess de Boigne |

Dorothea’s success in society was assured by her ability to

amuse; she had a cache of amusing stories and anecdotes to divert the bored.

Dorothea was not beautiful but was flirtatious around men and one of her

admirer’s was Harriet’s immensely rich brother-in-law Lord

Gower. Most women, bar Harriet, were dismissive of Dorothea, unable to see

the attraction she had for men.

Dorothea disliked other women she saw as competition, in

particular the other ambassadresses, most notably the Austrian Princess

Esterhazy. Most of her rivals were pretty, younger and of the old nobility.

It was Dorothea, not Christopher, who was courted by society; the French

ambassadress the Comtesse

de Boigne[viii],

said of him

‘Certainly

he was a man of breeding, and grand manners; but to the point, cold, but

polite....he was completely eclipsed by the incontestable superiority of his

wife, who affected to be very

attached and submissive towards him.’[ix]

|

| Comtesse de Perigord |

The Comtesse noted that Dorothea was feared but little

loved. Dorothea quickly made friends with the hero of the hour Arthur

Wellesley, the Duke of

Wellington, with whom she was reputed to have had an affair. To the circles

that Dorothea moved in marital fidelity was not important.

The end of the summer of 1816 saw Dorothea take a two week

trip to Paris; the Lievens were guests of honour at a dinner given by Pozzo di Borgo,

the Russian Ambassador to Paris. Dorothea noted that the women all wore

feathers in their hair and that Comtesse de

Périgord[x]

wore her hair dressed like a ‘pretty

serpent’ around her head. Talleyrand

himself sat next to Dorothea.

In the autumn of 1816 Dorothea became friendly with the Duchess

of Cumberland, whose quarrel[xi] with Queen

Charlotte meant that;

|

| Duchess of Cumberland |

The Prince Regent gave a dinner party in his sister-in-law’s

honour, but only that she might feel able to leave the country without

dishonour. Lady Stafford was the courtier delegated by the Prince to pass on

his message. Dorothea stood firm by the Duchess as she stood in shock and

Dorothea stood her friend for the three years the Duke and Duchess stayed in

England.

Depression

The following November saw Alexander marry Elisaveta Pavlovna Donez-Sacharshevskaya and

Dorothea mourned her bachelor brother, fearing that marriage would change him.

Dorothea saw Alexander as her closest relative, far closer than Christopher had

ever been.

Dorothea was happy to throw herself into the frenetic pace

of London society; she suffered from ennui and her frequent complaints of

illness arose from boredom. In the summer of 1818 Christopher took Dorothea

down to Brighton. And on the beach, in a fit of depression, Dorothea

contemplated death by drowning. She later wrote;

‘I

was quite well in myself, but I was so desperately depressed. My mind was so

vacant I could think of no reason for going on living……Lord Byron says terrible

and sublime things about death by drowning…..I felt that nothing could be

simpler than to stay on the point until the sea had covered it.’[xiii]

Only the failure of the tide to turn and wash her away left

Dorothea to continue contemplating the futility of life.

|

| Cathedral at Aachen |

The Congress of

Aix-la-Chapelle

In view of his wife’s precarious mental health Christopher

decided to take Dorothea with him when he travelled in the autumn of 1818 to Aix[xiv] for the Congress

that was to decide the future of Europe following Napoleon’s final fall. She

was pleased to be travelling to Aix.

And it was at Aix, on 22nd October that Dorothea

met Prince

Metternich, the Austrian Foreign Minister, at a reception given by Madame

Nesselrode. Three days later Metternich organised an excursion to Spa, where the party

spent the night; the Lievens and the Nesselrodes were his guests. Later Metternich

wrote to Dorothea;

|

| 1897 diorama of Spa |

‘I

began to see why those who described you as “an agreeable woman” were quite

right.’[xv]

The following day Metternich called on Dorothea and on 15th

November they became lovers. A few days later Dorothea had to accompany

Christopher to Brussels. They accompanied the newly arrived dowager Empress

Maria Feodorovna and Christopher’s mother. But Metternich soon found an excuse

to join Dorothea and the couple managed to spend four days together.

On 27th the Lievens returned to London where

Dorothea found outpourings of ‘love’

from Metternich awaiting her. Dorothea informed friends and family;

‘I

made some interesting acquaintances, of whom I shall always retain a pleasant

memory.’[xvi]

The affair was resuscitated briefly a couple of times but

the pair conducted a frank correspondence that lasted eight years. Metternich

liked to have a romantic female confidante and for the next eight years

Dorothea was to fulfil that role.

An Unexpected Arrival

_(1785-1867)%2C_by_Alfred_Edward_Chalon.jpg/451px-Sarah_Sophia_Child_Villiers%2C_Countess_of_Jersey_(n%C3%A9e_Fane)_(1785-1867)%2C_by_Alfred_Edward_Chalon.jpg) |

| Lady Jersey |

Dorothea had been feeling unwell towards the end of the

Lievens time in Brussels; at home she fell ill with an ‘inflammation of the throat and lungs’. Dorothea seemed unable to

throw off her bout of ill-health and soon discovered why she was feeling so

unwell; she was pregnant.

By early September Dorothea was visiting Lady Jersey at her

home in Middleton

to rest and prepare for her laying-in. Christopher’s duties found him much in

London and Dorothea had plenty of time to write passionate letters to

Metternich.

The Lievens fourth son George was born on 15th

October 1819. Christopher wrote to his brother;

‘In

spite of the serious fears with which she had approached the birth[xvii],

she had never had a happier confinement than this one.’[xviii]

George was named after the Prince Regent but the wits

quipped that Clement would have been more appropriate. There can be little

doubt that Christopher was George’s father as Dorothea and Metternich had not

seen each other since November 1818.

Bibliography

The Princess and the Politicians – John Charmley, Penguin

Books 2006

Talleyrand – Duff Cooper, Cassell Biographies 1987

Captain Gronow – Christopher Hibbert (ed), Kyle Cathie Ltd

1991

Wellington – Christopher Hibbert, Harper Collins 1997

Beau Brummell – Ian Kelly, Hodder Paperback 2005

Paris Between Empires – Philip Mansel, Phoenix Press

Paperback 2003

The Life and Times of George IV – Alan Palmer, Book Club

Associates 1972

The Russian Empire – Hugh Seton-Watson, Oxford University

Press 1988

Metternich – Desmond Seward, Viking 1991

Arch Intriguer – Priscilla Zamoyska, Heinemann Ltd 1957

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

Opened in 1765

[ii]

In 2014

the relative: historic standard of living value of that income or wealth is £655.90 economic status value of that income or wealth is £11,870.00 economic power value of that income or wealth is £39,590.00 www.measuringworth.com

[iv]

Whose memoirs are unreliable

[ix]

The Princess and the Politicians - Charmley

[x]

Married to Talleyrand’s nephew

[xi]

Neither she nor her husband approved of the fact that Frederica was divorced

[xii]

Arch Intriguer - Zamoyska

[xiii]

Ibid

[xiv]

Aachen

[xv]

Metternich - Seward

[xvi]

Ibid

[xvii]

Dorothea’s last child Konstantin had been born eleven years before

[xviii]

The Princess and the Politicians - Charmley

Some research suggests that the waltz may have been danced earlier at Almack's but the precise date is difficult to track down. Gronow's reminiscences are certainly very flaky, having been written decades later, though one has to assume his recollection of personalities are accurate enough, even if his dates and the precise patronesses of the time are suspect. Which is why that was the quote you chose, of course!

ReplyDeleteI am delighted by this post. Thank you very much.

ReplyDelete