|

| Dorothea Lieven |

Almost as soon as her feet touched English soil George

summonsed Dorothea to Brighton. He was interested in the paternity of his

godson and namesake George Lieven. The king had ascertained a likeness to

himself in young George, who looked very much like his father and even more so

his grandmother (still going strong at 72).

George had a very vivid imagination, and was prone to

telling his courtiers of the battles he had fought in during the Napoleonic

wars. Dorothea was well aware of this propensity and informed Metternich;

‘Up

to the present he says it as a joke; in a few days he will be saying it

menacingly; later he will let it be understood that he had good reason for

saying it; and still later he will persuade himself that he really can take the

credit.’[i]

George, when not caught up in flights of fancy, was no fool

and he was not pleased by the breakup of the Quintuple Alliance.

George was well aware of the need to keep an eye on Canning. Dorothea flattered

George by telling him that his presence at Verona had been sorely missed.

Spanish Intrigues

|

| Stratfield Saye |

Dorothea used the occasion of a visit to Stratfield Saye[ii] to stir up trouble

between Wellington and Canning, who had embarrassed Wellington in Verona. January

at Stratfield Saye was so cold that Dorothea had problems holding a pen[iii]. Dorothea found

Wellington rather a bore who was mostly happy to tell long rambling stories

about himself.

To counter Dorothea’s claims that he was a Jacobin Wellington showed

Dorothea his copies of the despatches he’d sent to London about the situation

in Spain.

|

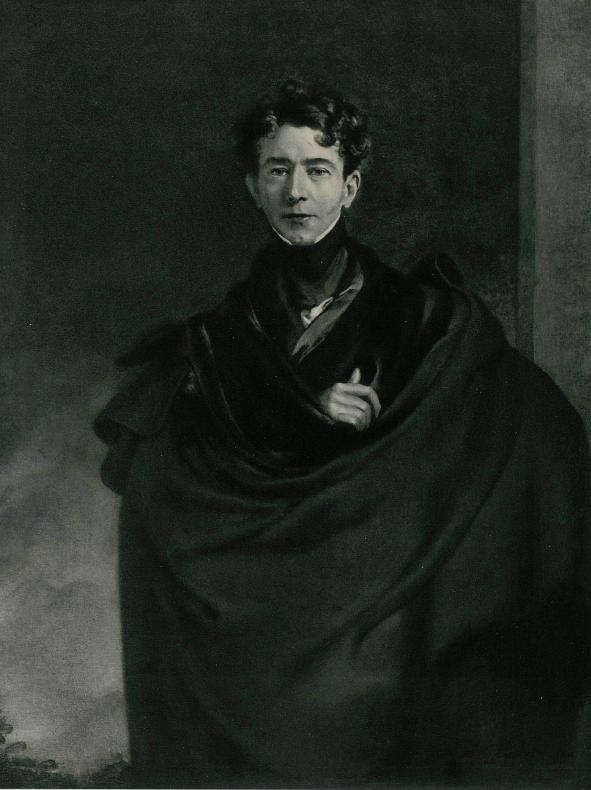

| Prince Esterhazy |

‘Damme,

I’ll show you what I wrote about Spain; and you will see if Metternich ever

said anything stronger.’[iv]

Dorothea persuaded him to show the papers to Christopher and

Prince

Esterhazy[v]

as well. But whatever Wellington’s opinion of matters in Spain, the British

public was firmly against intervention.

When French troops marched into their neighbour’s country

London shop windows were full of cartoons depicting Spanish patriots killing

the invaders. Canning, who had his finger on the pulse of public opinion,

refused to allow the sending of British troops to join the French.

The Anti-Canningites

Although popular with the country at large as a result of

his inflammatory speeches, Canning was not popular amongst his fellow

politicians and his sovereign detested him. Canning believed that a Europe

disunited would be good for Britain. Something the Whigs, Wellington and George

did not agree with.

|

| Duke of Wellington |

Canning’s unpopularity in political circles and abroad

continued unabated. European politicians were not impressed by Canning’s

attempts to align Britain with every revolutionary movement going. Canning hoped

to take over leadership of the Tory party from Lord Liverpool whenever that

worthy resigned; this put him at odds with Wellington who considered the

succession as his.

The Lievens gave a dinner party for Canning and the

Austrian, French[vi]

and Prussian ambassadors were also guests. Wellington, sat on Dorothea’s right,

spent the dinner whispering rude things about Canning, sat on Dorothea’s left.

To counter Wellington, Canning showed off and even Lady Granville, one of his

friends, was unable to smooth matters over. Dorothea was feeling unwell and not

up to assisting Lady Granville. Afterwards Christopher reproached Dorothea for

not spending more time talking to Canning himself

A Loyal Ambassadress

|

| Alexander von Benckendorff |

Paul had been sent back to school in Russia, under Alexander

von Benckendorff’s supervision. Her letters to Alexander imply that Paul was

viewed as a bad influence on his brothers;

‘I

am delighted to know that he is at school , and equally pleased to know that

you are prepared to show some sternness in dealing with him…..He has always

been extremely idle….he has always hindered his brothers’ progress that we

thought it advisable to separate them, and it must be allowed that since his

departure they have been going on famously.’[vii]

Dorothea had long outgrown her childish admiration for Christopher

who was called ‘Vraiment’ in

diplomatic circles, as this was the word he used most often. Christopher was

perfectly capable and used his wife dexterously to forward Russian interests.

Round about this time Dorothea started writing reports for Nesselrode,

supplementing the reports Christopher sent.

Dorothea was well-placed to act as liaison between Russia

and Britain; she was intimate with George IV and Lady Conygham and was good

friends with Wellington. Dorothea also kept Metternich informed with letters

sent via the Austrian Embassy. But, as she informed her lover;

‘Somebody

came and told me the other day, that I made an extremely clever compromise

between my duties and my personal views. I replied that I must do it far from

cleverly if people imagined that my duties and my personal views were not

identical.’[viii]

Desperate to keep Metternich’s attention focussed on herself

Dorothea kept dropping hints in her letters about a new admirer, Charles Lord Grey.

It is possible that Dorothea began an affair with Grey around this time to make

Metternich jealous.

Self-Imposed Exile

|

| Metternich |

Dorothea suffered a setback in her health in May 1823 and

she wondered whether she was going into a decline. In the summer Dorothea

committed an indiscretion; giving out that she was travelling for her health

which could not support another British winter, Dorothea arranged to meet

Metternich in Milan.

Despite their imminent meeting Dorothea begged Metternich to

continue writing to her with news of what was going on in the world;

‘My

husband is the soul of prudence.....it is the same with the letters the Duke of

Wellington will write me. So, without you, I run the risk of relapsing

conventional feminine role; and it seems to me that it would be a pity.’[ix]

Dorothea got her kicks from being a powerful go-between and

was naturally reluctant to relinquish the importance placed on her by Nesselrode

and the Czar as a result of her liaison with a key player in Europe.

When she arrived in Milan Dorothea was disappointed to learn

that she would have little time with him, despite his promises. Dorothea spent

the winter in Florence, Rome where she met Lord Kinnaird[x], while Metternich

travelled around Europe desperate to keep up support for the Greek

insurrection. He did not reply to Dorothea’s letters or provocations.

Dorothea took four year old George with her to Italy and, as

ever when she was apart from him, Dorothea missed her husband as did George.

‘At

our age and with our experience, domestic happiness is the most important

thing, one cannot replace the confidence and habits of a marriage….Mon bon ami,

we are both suffering now because of our need for each other, which will still

bring us great happiness.’[xi]

|

| Christopher von Lieven |

When Dorothea told Metternich that Christopher wanted her to

come home he did not respond to this provocation either. Dorothea was caught by

the lies she had told at home in order to travel abroad. Dorothea did not

return home until May 1824, her passion for Metternich all but spent. She was

met at Dover by Christopher and they travelled back to London.

Another Pregnancy

Dorothea now contemplated returning home to Russia to see

old friends. The British government offered her the King’s yacht to take her to

St Petersburg. She planned to meet Metternich in June en route.

Dorothea reached Dover when the journey halted, not to be

resumed. Christopher was the one who stopped Dorothea’s travelling when

Dorothea realised that she might be pregnant again. At the age of nearly forty

this was to be her sixth child and the journey home to Russia was long and

precipitous at the best of times.

|

| Lady Conygnham |

Dorothea was the link between George, Wellington and

Metternich. Spending a lot of time at with George, Dorothea found herself

subject to George’s amorous attentions much to the irritation of Lady Conyngham.

Dorothea’s pregnancy was giving her the more voluptuous figure that George

preferred.

In July Wellington gave a grand dinner for the King; the

hated Canning and the Lievens were also invited. Dorothea flirted with and

embarrassed Canning. Dorothea asked him to dine and he in turned picked her

brains for information about the Parisian scene. They talked together at a

reception hosted by Lady Hertford.

In the autumn Dorothea commenced a correspondence with Lord

Grey. In later years she claimed that their relationship;

‘Remained

natural to our situations, he very English and I very Russian; but we allowed

ourselves a rare degree of confidence, which I never betrayed.’[xii]

In her correspondence Dorothea reported conversations

verbatim, useful for any politician, and witty social and political gossip

along with details of political events.

Dorothea and Christopher’s fifth son was born in late

February 1825 and named Arthur after Dorothea’s friend Wellington who was his

Godfather. The confinement had been difficult and for some time afterwards

Dorothea was confined to bed or a sofa. She wrote to her brother;

‘I

have another boy, much to our mutual regret…..he is remarkably pretty…..The

news Paul tells me of himself gives me great pleasure….he is delighted with his

start in life[xiii], and speaks in high

praise of the Foreign Office.’[xiv]

When Metternich’s wife Eleanore died in Paris in March 1825

and Dorothea wrote to console her friend.

Bibliography

The Princess and the Politicians – John Charmley, Penguin

Books 2006

Captain Gronow – Christopher Hibbert (ed), Kyle Cathie Ltd

1991

Wellington – Christopher Hibbert, Harper Collins 1997

Paris Between Empires – Philip Mansel, Phoenix Press

Paperback 2003

The Life and Times of George IV – Alan Palmer, Book Club

Associates 1972

Princess Lieven’s Letters – Lionel G Robinson (ed),

Longmans, Green & Co 1902

The Russian Empire – Hugh Seton-Watson, Oxford University

Press 1988

Metternich – Desmond Seward, Viking 1991

Arch Intriguer – Priscilla Zamoyska, Heinemann Ltd 1957

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

The Princess and the Politicians - Charmley

[ii]

Wellington’s country home, bought by a grateful nation in 1817 for £263,000; in 2014 the relative: historic standard of

living value of that income or wealth

is £17,200,000.00 economic status value of

that income or wealth is £323,900,000.00 economic power value of that income or wealth is £1,029,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[iii]

The Duchess of Wellington was not a capable lady of the house and the rooms at

Stratfield Saye were insufficiently heated

[iv]

Arch Intriguer - Zamoyska

[v]

Austrian ambassador to Great Britain

[vii]

Princess Lieven’s Letters – Robinson

[viii]

Arch Intriguer - Zamoyska

[ix]

The Princess and the Politicians - Charmley

[x]

A friend of Byron’s

[xi]

Arch Intriguer - Zamoyska

[xii]

Ibid

[xiii]

Nesselrode had given him a job

[xiv]

Princess Lieven’s Letters – Robinson

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.