|

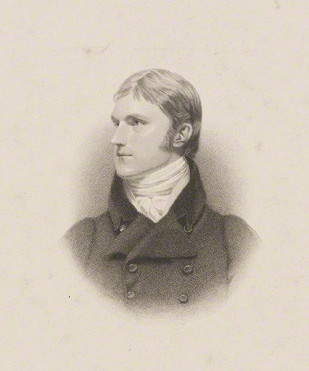

| Stratford Canning |

Foreign Provocation

Further provocation to the British government came with

Russian interference in Portugal. The infant queen Dona Maria’s

liberal advisers caused alarm to the Czar and his far from liberal advisers. By

March 1833 Palmerston informed Christopher that Canning’s nomination as

ambassador to St Petersburg was confirmed.

Britain claimed that Russian objections really boiled down

to the fact that Canning, as the former ambassador to the Sublime Porte, knew far too

much about Russian actions in the eastern Mediterranean[i]. In May 1834, no longer

able to ignore the anti-Russian rhetoric of the British media, the Czar

recalled the Lievens. The idea of leaving her home in England horrified Dorothea.

When the order came Dorothea was in despair

‘My

husband threw up his hands with joy, and I mine with sorrow.’[ii]

On 23rd May the Times published a

vindictive article attacking Dorothea. Talleyrand’s mistress the Duchess de

Dino[iii] commiserated with

Dorothea claiming the article to be a ‘national

disgrace.’ Dorothea was horrified by the attack.

|

| Sir James Graham |

On 28th May[iv] Palmerstone, as was

customary, threw a dinner for the ambassadors and their wives/mistresses. He

sat with Dorothea de Dino on one side and Dorothea de Lieven on the other.

Dorothea was making a statement in the new national dress which St Petersburg

had decreed should be adopted for state occasions. In the midst of a round of

farewell parties for the Lievens Grey resigned on 10th July to be

replaced by Melbourne.

In July Dorothea was informing Alexander that the First

Lord of the Admiralty, Sir James

Graham, had offered the Lievens a ship to take them to either Hamburg or St

Petersburg. Dorothea was concerned about the packing up of a household and

sending it abroad.

‘What

a nuisance it is to carry off or throw away the contents of a house like

ours…..We are bringing away all that is useful for the household….I imagine that

we would find our new home furnished. I am getting impatient to find out where

that new home will be, and you leave me, dear Alexander, in complete darkness

on such points.’[v]

Even by mid-July she and Christopher had not been informed

where they would be going or what post Christopher was to take up.

Leaving Home

|

| the Summer Palace |

Once back in Russia Dorothea found she loved the idea of her

homeland more than the reality. Christopher had been given the important post

of the Governor of the heir to the throne the Czarevitch Alexander, whose tutor was the poet Vasily Zhukovsky. The

Lievens lived in apartments at the Summer

Palace[vi] at Tsarskoe Selo.

|

| Czarevitch Alexander |

Christopher was only required to meet with the Czarevitch

for one hour a week on a Sunday. Characteristically Dorothea took over and

started having long conversations with the 17 year old boy. During the day

Dorothea met with the Imperial children and in the evenings had friends for

dinner;

‘The

Czarewitch shows a desire to profit by my evening gatherings and accustom

himself to the forms and ways of general society. He asks many questions and

listens attentively to what is said in reply. I try to get him to talk and tell

stories. Above all I try not to bore him…’[vii]

But used to a far more varied and intense life, Dorothea

soon became bored and characteristically started worrying about her health.

‘Our

existence is honourable and brilliant but I would love it more if I were able

to forget England, and if I did not live in a climate made for bears.

She wrote to her friends in England, keeping in touch with

the political shenanigans that she had once been so closely embroiled in.

Tragedy

In February 1835 Dorothea was to lose the second of her

children to predecease her; George went down with scarlet fever[viii], he died in March aged

16. And then in April tragedy struck again. The 10 year old Arthur, who had

started to recover from the infection, had a relapse and died. In a letter to

Lord Grey Dorothea wrote’;

‘My

dear friend, what can I write? I have no words left, and what can you say to

comfort me? Was any bereavement more complete than mine?’[ix]

|

| Baden-Baden |

The two boys were buried at the Lieven estate at Mežotne. Christopher and the Czar decided that Dorothea needed to be

diverted from her sorrows and Christopher escorted her to Berlin to see a

doctor. Dorothea wrote to Alexander;

‘He

[Christopher] is kindness itself to me. It will be a bad moment when we must

separate, for my dear brother, it will be for good. I can no longer live a life

without interest and without occupation.’[x]

Dorothea had decided never to return home and she knew that

Christopher would not gainsay the Czar. Paul Lieven visited his mother in

Berlin and was shocked at his mother’s condition. Dorothea started a tour

around the German spa towns; in Baden-Baden she met with Countess

Nesselrode who informed her that the Czar was unhappy with her. Dorothea told

Alexander that her doctor had advised that she move to Paris; she was never to

see her husband again.

Interest in Paris

|

| Les Tuileries |

Dorothea took a small apartment on the Rue Castiglione near

the Tuileries Gardens.

She kept up her voluminous correspondence but even so she lapsed into

depression writing to Christopher;

‘Bon ami, cher mari, how sad and unhappy

I am. I have horrible terrifying moments when I feel I am suffocating[xi],

and death takes me by the throat; then I pray to God – it is all I can do……I

often think about you after my angels, for they are always foremost in my

thoughts.’[xii]

When the Corps

Diplomatique returned to town after the summer holidays Dorothea’s spirits

rose. Her friend Lady Granville was the British ambassadress. Dorothea had many

visitors to her little apartment including the Duc

d’Orléans[xiii]

and the Ministers of the Crown including one François Guizot[xiv].

|

| Victoria |

Guizot’s father had been guillotined during the terror and

his mother had taken Guizot to Geneva

where he learnt the carpenter’s trade. In February 1837 Guizot, a widower, lost

his son and Dorothea immediately wrote a letter of condolence. He was to offer

her a continued window into the political world. Dorothea felt she had found a

soulmate.

In July 1837 Dorothea paid a short visit back to the country

where she had known such happiness. There she was introduced to the young Queen Victoria, the

conversation was reserved as the queen had been warned to be on her guard in

the presence of a notorious intriguer. While there Dorothea received a summons

home. St Petersburg was concerned about her involvement in politicking.

Intemperate Demands

|

| Count Orlov |

Christopher had been escorting the Czarevitch on a tour of

the Russian empire. He wrote to Dorothea informing her of her recall and

appointing a meeting in Italy. From there he would escort her home. As ever,

Dorothea had recourse to her bad health and immediately fell ill.

Back in Paris Dorothea tried to postpone the recall using

the medium of Count

Orlov, Russian Ambassador in Paris. Under orders from above, Christopher

replied;

‘I

am obliged to account for any delay on the decision I must take if you refuse

my request…..I insist you come to me. I have warned you that if you refuse I

shall be obliged to take measures that will be very disagreeable to me. If you

do not return I shall cease to support you.’[xv]

|

| Alexander von Benckendorff |

Dorothea’s son Alexander was despatched to Paris in an

attempt to persuade his mother to return home. From him she discovered that

Christopher was not reading the letters from her doctors stating that

Dorothea’s health would suffer if she returned to Russia. Nor had he informed

the Czar.

Writing to her brother Alexander was of no help either; he

was most discouraging in his replies to Dorothea’s pleas. Dorothea’s allowance

was cut off in March 1838 and in retaliation she decided to sell her diamonds

in England where she would get a better price. Christopher stopped

corresponding with his wife for several months, but finally relented at

restarted her allowance in June when he paid her 4,000 francs a month.

Further Tragedy

|

| Francois Guizot |

Christopher asked to meet Dorothea in August 1838 in Baden;

despite encouragement from Guizot, Dorothea refused to go as she was allegedly

not fit enough to travel and claimed that Guizot was trying to get rid of her.

In June 1838 Constantine died in America. He had been sent

there as his life in Russia was one of dissipation. Christopher did not inform

Dorothea of her son’s death and she was shocked to have her letters to

Constantine returned to her. She wrote to Lord Grey;

‘They

bear simply the statement written on the cover that he is dead….my husband has

left me in total ignorance of the event, apparently wishing me to learn it in

the brutal manner I have just done.’[xvi]

Christopher wrote to Dorothea again in December telling her

he would join her once his current work was finished and they would live

wherever was best for her. Dorothea was not impressed by his letter and asked

Lady Cowper to reply on her behalf. On 10th January 1839 Christopher

died in Rome while escorting the Czarevitch on his Grand Tour.

The Final Act

After Christopher’s death Dorothea received a note from her

husband written before his death;

‘Good-bye,

chère amie, I embrace you tenderly.’[xvii]

|

| Dorothea de Dino |

Despite his overriding attention to duty to his Czar,

Christopher had always loved Dorothea far more than she loved him. For a while

Dorothea was prostrated by grief, but soon returned to her social whirl meeting

with Dorothea de Dino and other close friends. And of course there was always

Guizot, her last love.

Once Christopher’s estate was settled Dorothea had £1,000[xviii] per annum to live on.

The politicians du jour and their hangers on attended Dorothea’s salon and when

Guizot was appointed Ambassador to London in 1840 Dorothea was able to smooth

the way with introductions to her friends

Apart from a brief visit in August 1840 Dorothea did not

visit England until the revolution of

1848 forced her and Guizot to flee France. They lived in Brighton; at the

end of 1849 Guizot and Dorothea returned to Paris. As a Russian citizen she had

to leave at the commencement of the Crimean war but returned

to her old life with Guizot in in 1856.

In January 1857 Dorothea

came down with bronchitis which quickly turned to pneumonia. On 27th

January 1857 Dorothea died peacefully at her home, 2 rue Saint-Florentin in

Paris. Guizot and her son Paul were with her when she died. Dorothea was

buried, according to her wish, at the Lieven family estate near Mežotne, next

to her two young sons George and Albert.

Bibliography

Melbourne – David Cecil, The Reprint Society Ltd 1955

The Princess and the Politicians – John Charmley, Penguin

Books 2006

Talleyrand – Duff Cooper, Cassell Biographies 1987

Paris Between Empires – Philip Mansel, Phoenix Press

Paperback 2003

Princess Lieven’s Letters – Lionel G Robinson (ed),

Longmans, Green & Co 1902

The Russian Empire – Hugh Seton-Watson, Oxford University

Press 1988

Metternich – Desmond Seward, Viking 1991

Arch Intriguer – Priscilla Zamoyska, Heinemann Ltd 1957

Melbourne – Philip Ziegler, Fontana 1978

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

With the Treaty

of Unkiar-Iskelesi dated 8th July 1833 Russia had come to

agreement with the Khedive

of Egypt, formerly party of the Ottoman empire

[ii]

Arch Intriguer - Zamoyska

[iii]

Dorothea de Dino had divorced her husband and moved in with his uncle

[iv]

The king’s birthday

[v]

Princess Lieven’s Letters - Robinson

[vi]

The Alexander Palace

[vii]

Arch Intriguer - Zamoyska

[viii]

Or Scarlatina

[ix]

The Princess and the Politicians - Charmley

[x]

Arch Intriguer - Zamoyska

[xi]

Possibly panic attacks

[xii]

Arch Intriguer - Zamoyska

[xiv]

His work at the Ministry of Education was essential in the passing of a law in June 1833 which established and organized

primary education in France.

[xv]

Arch Intriguer - Zamoyska

[xvi]

Ibid

[xvii]

Ibid

[xviii]

In 2014

the relative: historic standard of living value of that income or wealth is £78,590.00 economic status value of that income or wealth is £1,302,000.00 economic power value of that income or wealth is £3,171,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

Thank you so much for this brilliant series about a fascinating lady.

ReplyDeleteA most unhappy life, I presume she used politics as a substitute for love and happiness. Poor Dorothea.

ReplyDelete