|

| Battle of Navarino |

George appointed one of Canning’s non-entities, Lord

Goderich as Canning’s replacement. Dorothea’s opinion of him was trenchant,

describing Goderich;

‘As

cowardly as the most timid woman.’[i]

Goderich’s indecisiveness may have been a contributory cause

when in October 1827 the Turkish-Greek conflict erupted anew. The

French/Russian/British allied fleet closed with the Turco-Egyptian fleet and

destroyed it at the battle

of Navarino. The second

Russo-Turkish war did not start in earnest until the following April when

the sultan closed the Dardanelles

to Russian ships.

|

| Lord Goderich |

In January 1828 the indecisive Goderich resigned under

pressure from the king and George was asked Wellington to be his Prime

Minister. Dorothea made attempts to charm the great man. Harriet Arbuthnot

wrote;

‘She

[Dorothea] sat by the Duke at dinner and……she took him to sit by her on a sofa

apart from everyone else and then she had a tête-à-tête

with him the whole evening. As soon, however, as she went away, he let us

know that the conversation had not touched on politics.’[ii]

Wellington had not forgiven Dorothea her support of his former

rival and Dorothea’s mortification was increased by the knowledge that her

rival Princess Esterhazy was friendly with the great man. Lord Palmerston

wrote;

‘The

Duke has had violent quarrels with the Lievens. A great many things have

contributed to set him against [them]......[he] thought himself not civilly

used at St Petersburg....Mrs Arbuthnot and Lady Jersey....both hate Mme de

Lieven.’[iii]

Unwonted Interference

|

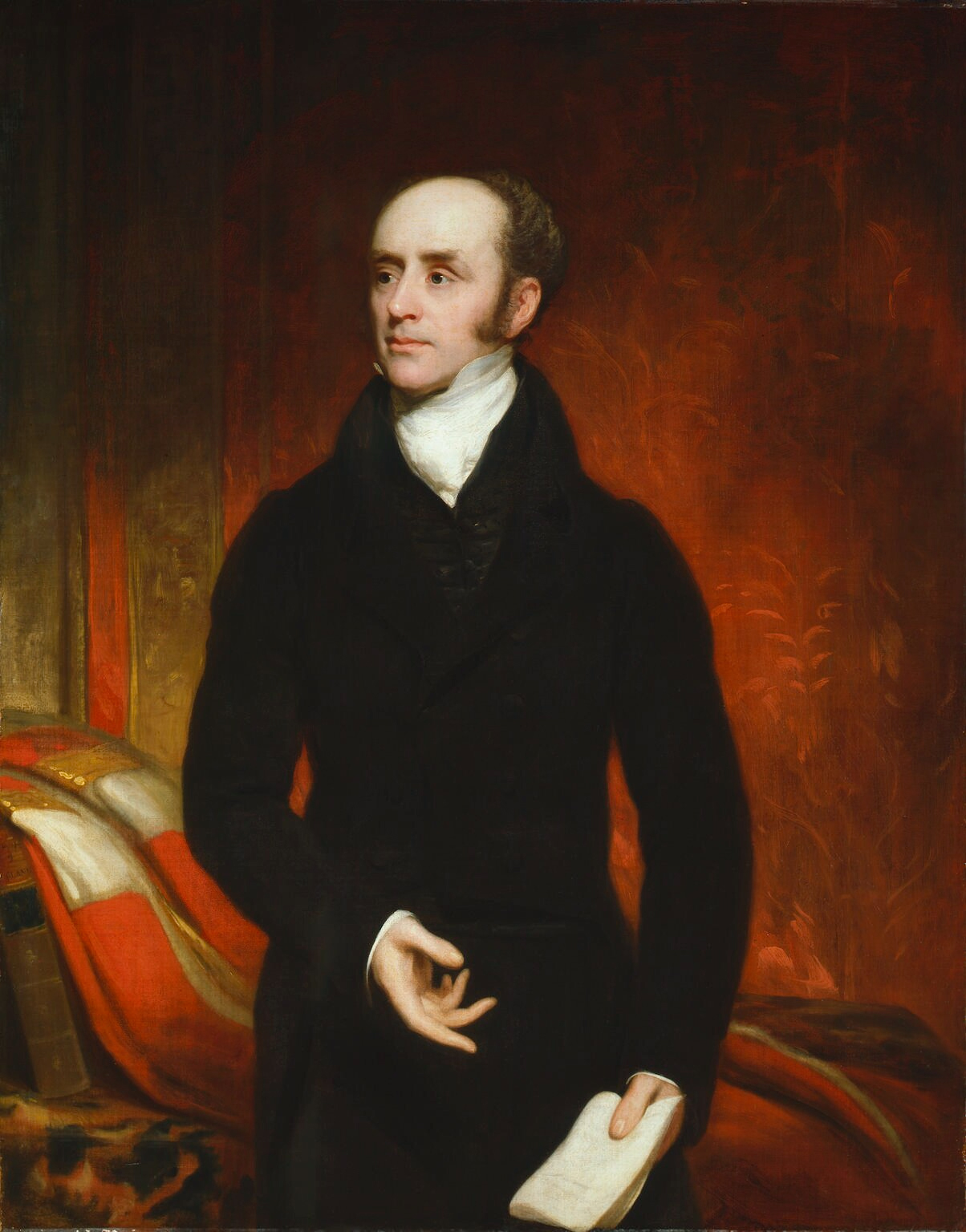

| Lord Grey |

At home Dorothea was busy trying to give backbone to

Canning’s remaining supporters. She used her charms on Lord Grey, with whom

George would not deal with at any price. Dorothea fed Grey with titbits of

Russian intelligence and assured him of her fondness for him. Dorothea’s aim

was to stop British intervention in the event that the Russians did go to war

with the Ottoman Empire.

But Dorothea was working on a fallacious conclusion,

believing that Wellington could be manipulated through Canning’s former

supporters. Palmerston was one of the most vociferous in denouncing

Wellington’s intentions towards the Russians. Dorothea’s actions were soon so

actively anti-British that Wellington considered asking for the Leivens recall.

Harriet Arbuthnot noted that Dorothea;

‘Disgusted

all parties by her uncalled interference in our internal affairs.’[iv]

Dorothea set herself the task of forming an alternative to

Wellington and had her prime minister in Grey. Her correspondence with him

multiplied and Grey’s letters to Dorothea were scented with musk. The pair may,

or may not, have been lovers; Grey certainly had a reputation as a great lover[v]. Believing that men like

Grey and Palmerston would be more pro-Russian than Wellington, Dorothea pressed

the pair to push for power.

Inharmonious Relations

Dorothea was not pleased when Christopher applied for home

leave. His mother died in March 1828 and Christopher wanted to sort out her

affairs. Dorothea passionately believed that they were both needed in England Dorothea

wrote to her brother;

‘I

am a little annoyed, I must admit, that my husband should have asked for leave

for private business, I have done my utmost to hinder it, my reasons being the

importance of the present state of public affairs,; his, the future welfare of

his children and his duty to look after it.’[vi]

Paul Lieven longed to join the fray in Greece but ended up

in St Petersburg dealing with the family affairs as his father was refused

leave to return home[vii].

The relationship between Dorothea and Christopher became so bad that the couple

ended up corresponding via notes, despite living in the same house, each

blaming the other for the rift which was patched up temporarily.

Christopher believed that he was being blamed by his fellow

ambassadors and British politicians for failing to control the headstrong

Dorothea. Dorothea protested her love and devotion to Christopher and then said

she would leave him unless his behaviour improved. It was the view of the

majority, including the Austrian ambassador that Christopher was;

‘[A]

good kind of man, well-intentioned &, if left alone, would be peaceably

inclined, but that he was driven on by his wife.’[viii]

Working Relations

.jpg) |

| Prince Leopold of Coburg |

Despite their inharmonious relations the Lievens managed a

trip during 1828 to visit Prince Leopold of

Coburg[ix][x].

Dorothea suggested to Christopher that Leopold was interested in becoming King

of Greece. All the powers had their favoured candidates; Austria supported the

pretensions of Prince

Philip of Homburg, while the French favoured a Catholic candidate.

Dorothea drove a cart and horses through the normal

diplomatic niceties; she even tried to turn the British Ambassador to Russia, Lord

Heytesbury, against his own government. Christopher went off on a tour of Birmingham and the

provinces, while Dorothea hunted the drawing rooms of London for information

useful for the Russian government.

In an attempt to break the deadlock Wellington tried to

return his relationship with Dorothea to its old footing, but Dorothea was

having none of it. Heytesbury informed Wellington that the Czar believed that

Wellington was responsible for the outbreak of British hostility to Russia

since the outbreak of the war. Much of this was due to Dorothea’s

interpretation of events in Britain.

I

n August 1828 another death caused grief in the Lieven

family; Dorothea’s brother Constantine died of a fever that swept through the

Russian army, during the war with the Turks. His troops had recently captured Ezmiadzin and routed the

Kurds near Yerevan. They then crossed the Araks River and defeated the Turkish cavalry.

Constantine left a wife and two children.

|

| Echmiadzin |

‘Last

evening I learnt by a letter from Count Nessselrode that our angelic

Constantine had been snatched away! One after another I lose all whom I love –

my cup of sorrow is indeed bitter…..Poor dear Constantine, what will become of

his poor children?’[xi]

Dorothea was upset by Constantine’s death, but she was not

as close to him as to her faithful correspondent Alexander.

Fatal Errors

_by_Sir_George_Hayter.jpg) |

| Duke of Wellington |

Dorothea campaigned against Wellington’s attempts to

emancipate the Catholics purely because it was a piece of legislation that

Wellington wanted to push through parliament. Wellington supported the bill

mainly because he was informed that public opinion strongly supported the bill.

‘The

Duke of Wellington has been obliged to make himself a Liberal…..the Catholic

Emancipation bill has passed the Commons, but the Lords are going to throw it

out.’[xii]

For herself Dorothea supported Catholic emancipation, but

saw it as a way of defeating her former friend. From now on the recall of the

Lievens was frequently discussed in government circles. Wellington believed

that the couple were the cause of the estrangement between the two countries.

In the spring of 1829 Dorothea’s enemies were briefly elated

when the Lievens were recalled to St Petersburg. Czar Nicholas sent Count Matuscewitz

to replace Christopher who was merely covering as Foreign Minister while

Nesselrode took a break. It was believed that Matuscewitz was in England to

assess what the Lievens were actually doing.

Lord

Aberdeen[xiii]

took advantage of Matuscewitz’ presence to make him aware just how much damage

Dorothea was doing to Britain’s relations with Russia. It was no easy task as

Christopher was in high favour with the Czar as a result of his close

connection with the royal family, while Dorothea’s brother Alexander, as head

of the secret police, was highly influential.

A Russian Interlude

|

| Alexander von Benckendorf |

The Lievens left for Russia in July taking the boys and Miss

Smith, their English governess, with them. Dorothea was not in favour at court,

her support for the Canningites, well past their sell-date, was not

appreciated. Even Alexander refused to house her for fear of losing the Czar’s

favour[xiv]. They did not stay long,

although Christopher had wanted to spend time dealing with his own affairs; he

had property in Russia, inherited from his mother and estates in Courland.

Once home Dorothea wrote a censorious letter to Alexander;

‘You

have offended me and wounded my feelings, my brother: the hurt you have done me

will never be effaced. Never would our dear Constantine have been capable of

treating me in such a way, but then he loved me.’’[xv]

Yet it was not long before she was again writing to him with

all her political news. Matuscewitz returned home in September and Dorothea

warned Alexander that he had conceived an ‘excessive

devotion’ to England.

The Throne of Greece

|

| Triumphal gate erected in St Petersburg following the Russian victory |

The Russian war with the Turks ended in September 1829 with

the Treaty

of Adrianople. The British government’s war

with the Lievens was still ongoing in March 1830 when Lord Aberdeen lost

patience with the softly, softly approach Heytesbury was taking. Wellington was

angered by Dorothea’s interfering in British politics writing to Lord Aberdeen

who had been a guest at a Leiven dinner party not long before and now counted

himself among Dorothea’s friends;

‘Ever

since I became Prime Minister the de Lievens have been meddling in party

politics against me…..I have proof that they are the only cause of estrangement

between our two countries…..their behaviour would justify demanding Prince

Lieven’s recall. But I think this would do more harm than good.’[xvi]

In his correspondence with her Lord Grey advised Dorothea

that her actions were causing upset amongst senior government members, but she

failed to take note.

The question exercising the three main powers was who was to

take the throne of Greece; and Leopold’s name came out top. In February 1830 a

conference of the Powers was held in London and the Lievens gave a ball.

Wellington snubbed the Lievens by declining his invitation. The conference

resulted in the London

Protocol. Leopold had his eye on the main chance and hoped for better

things; he turned down the Greek throne.

Bibliography

Melbourne – David Cecil, The Reprint Society Ltd 1955

The Princess and the Politicians – John Charmley, Penguin

Books 2006

Wellington – Christopher Hibbert, Harper Collins 1997

Paris Between Empires – Philip Mansel, Phoenix Press

Paperback 2003

The Life and Times of George IV – Alan Palmer, Book Club

Associates 1972

Princess Lieven’s Letters – Lionel G Robinson (ed),

Longmans, Green & Co 1902

The Russian Empire – Hugh Seton-Watson, Oxford University

Press 1988

Metternich – Desmond Seward, Viking 1991

Arch Intriguer – Priscilla Zamoyska, Heinemann Ltd 1957

Melbourne – Philip Ziegler, Fontana 1978

[i]

Wellington - Hibbert

[ii]

Arch Intriguer - Zamoyska

[iii]

Wellington - Hibbert

[iv]

The Princess and the Politicians - Charmley

[vi]

Princess Lieven’s Letters - Robinson

[vii]

The estate at Mežotne was inherited

by Christopher’s brother Johan

[viii]

The Princess and the Politicians - Charmley

[ix]

Widower of the unhappy Princess Charlotte

[x]

The Lievens had stayed in communication with Leopold after the death of

Princess Charlotte

[xi]

Princess Lieven’s Letters - Robinson

[xii]

Arch Intriguer - Zamoyska

[xiii]

Currently Foreign Secretary

[xiv]

This may have been a direct instruction from the Czar

[xv]

Princess Lieven’s Letters - Robinson

[xvi]

Wellington - Hibbert

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.