|

| William II de la Marck |

Guerrilla

fighters, members of the Beggars’ bands, lived in the woods and harassed the

Spanish whenever they could. Their disorderly conduct on land had made them

unwelcome visitors wherever they landed, but their piratical conduct filled

William’s treasury anew.

The most

noteworthy of a series of unruly captains was William II de la Marck, a genial ruffian descended from a

line of robber barons. William regularly changed the leaders of the Sea Beggars

in the vain attempt of bringing them under control.

On 21st

February 1572 the Sea Beggars were expelled from English ports where they had

been allowed refuge. Being expelled from England had one unexpected and welcome

result for the Sea Beggars; on 1st April 1572 they captured Brielle, providing the first foothold on land

for the rebels.

Brielle harboured about 25 ships and 7-800 fighting men. The

Dutch punned on the Flemish meaning of the word brielle;

| Vlissigen |

‘The Duke of Alva lost his

spectacles on All Fools Day.’[i]

Louis and

the rest of the fleet sailed up the Schedlt and went on to capture Vlissingen on 6th April. He followed this victory up by

taking Mons in May 1572. The capture of the

towns was the inspiration for uprisings throughout the provinces. Zealand

Friesland and part of Holland all declared for the Prince of Orange.

Seizing the Moment

|

| Frankfurt |

William

seized the moment and ordered that all Spanish taxes be remitted, all

privileges restored, there was to be liberty of conscience for all[ii] and there was to be no

plundering (something the Sea Beggars did not think pertained to themselves) or

victimisation. The German princes gathered at Dillenburg, were unwilling to

commit themselves.

The Dutch

merchants sent one of their own with 100,000 florins[iii] as a loan for William’s

war expenses. Impressed by the Dutch fervour the princes granted William

recruitment rights in their lands. William spent June in Frankfurt raising money from

every banker who was prepared to, however little the loan.

On 28th

June William left Dillenburg with 1,000 horse. At Siegen a further 4,000 were

waiting; by the time he reached Essen he had 20,000 men. In July the deputies

of the cities involved in the revolt met at Dordrecht and William was chosen as

the commander in chief of the rebel armies. From Guelderland in August William wrote to his brother John;

‘I have come to make my

grave in this land.’

He was never

to leave the Netherlands again.

Blow and Counterblow

|

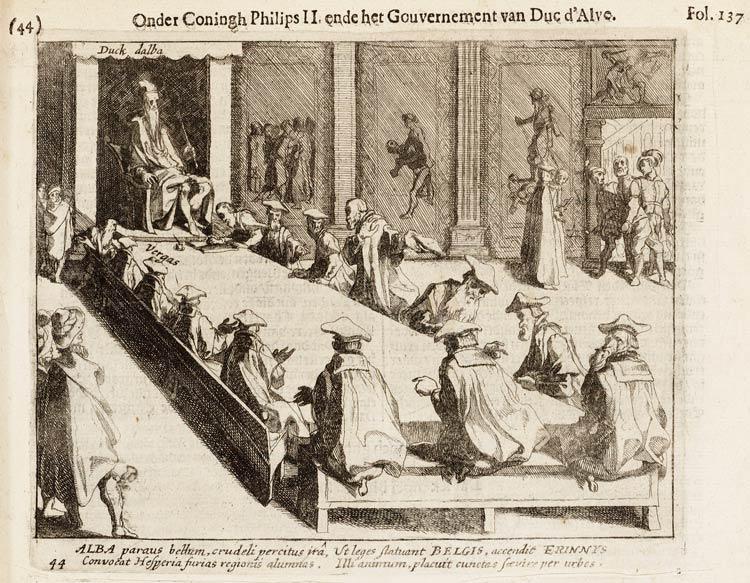

| Council of Blood |

Alba had

filled the senior positions at his court with Spaniards, Spanish was the

language of the court and although Philip issued a pardon for those who were

marginally involved in the uprising, Alva did not publish it for six months.

Even then it was a very imprecise document and those owning up could very well

find themselves in further trouble. The preferment of all things Spanish caused

an intense hatred of the Spanish to start percolating through the Netherlands.

By 1572 the

Council of Blood had sent over 6,000 Dutch citizens to the execution block or

gallows. And bone fires burned with impressive regularity in Dutch towns for

those who would not abjure their Protestant faith. Regular caravans of

emigrants left for the Rhineland and by the shipload for England, from whence

arms and ammunition were imported.

Alba’s

attempt early in 1572 to introduce a new tax called the Tenth Penny was a

dismal failure. The tax was detested and when the burghers of Gouda called upon

the guard to defend the town against the rebels they were told;

‘No; for the Tenth Penny we

won’t lift a finger.’[iv]

In the spring

of 1572 Juan de la Cerda, Duke of Medinaceli, was sent to the Netherlands as governor; Philip had lost

faith in Alba’s blood bath. Medinaceli was not impressed by Alba’s methods,

reporting back to Madrid;

‘Excessive rigour, the

misconduct of some officers and soldiers, and the Tenth Penny, are the cause of

all the ills and not heresy or rebellion.’[v]

Medinaceli

believed in following the more conciliatory policies of Philip’s father Charles

V. He lobbied Philip for Alba to be replaced as military commander; his brutal

policies were clearly only turning the Dutch to support their hero the Prince

of Orange. Alba by this time was desperately weary of the fight and desperate

to return home to Spain.

William

determined to take the provinces one by one and made a fortress in the north

where the Sea Beggars could protect them from incursions by the Spanish. The

invasion had been predicated on a[vi] diversionary invasion

from the south by the Huguenots.

Spanish Revenge

|

| St Bartholomew's Day Massacre |

On 24th

August, when William took Roermond[vii], the faction in France supporting

the Duc de Guise[viii] had Admiral Coligny assassinated;

the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of prominent Huguenots[ix] had begun[x]. The Huguenots were placed

on the back foot as most of their number were murdered in Paris. Now they were

in no position to follow up on their promises to support the Dutch in their

rebellion.

Philip was

jubilant at this strike at the heretics, while the Pope struck a medal in the

assassins’ honour. Alba alone was not heartened by the attack; William

reorganised his plans with an attempted assault on Jemappes, deep in Flanders. One of Alba’s lieutenants, Julian Romero[xi], led a raid on the rebel camp and

William was almost killed. He was woken from sleep by his dog Kuntze, who

barked at the attackers. Louis, who had barricaded himself in Mons, was allowed to march out

with the honours of war on 19th September.

|

| Don Fadrique de Toledo |

Don Fadrique de Toledo, Alba’s son and heir, led the

Spanish counter-surge with orders to spare the rebels; men or women or cities.

They retook Zutphen, sacking the city and hanging the

soldiers of the garrison over the walls by their feet. Mechelen too was retaken and the townspeople massacred. By the time winter

arrived, to freeze the armies in position, William and his supporters held one

third of Holland, the coastline of Zealand and parts of Friesland.

Amsterdam

was not part of the general uprising; the merchants there felt that stability

was only to be found with the Spanish and invited them in. This killed off

their sea trade routes through the Zuider Zee[xii], controlled by the Sea Beggars. Don

Fadrique commanded the Spanish troops against the town of Haarlem, which under the leadership of Wigbolt van Ripperda withstood the Spanish siege for seven months. William hoped that Louis would be able to

create a diversion and draw off the besiegers, he wrote to his brother;

‘The whole country awaits

your coming like the Angel Gabriel.’[xiii]

|

| Wigbolt van Ripperda |

But Louis

was in France trying to wheedle support out of Catherine de’ Medici; an embassy

too important to abandon. Haarlem surrendered on 12th July 1573,

after the relieving force had been annihilated on 7th. Wigbolt and

his associates were beheaded.

The Spanish

next turned their attention on Alkmaar, hoping to divide the provinces and seal off the rebels. The siege began on 21st August; the garrison included a

detachment of English and Scots soldiers and included a few survivors from the

Haarlem siege. By October the joint forces had seen off the Spanish and the

hated Don Fadrique

Bibliography

The Age of

Religious Wars – Richard S Dunn, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1971

The Revolt

of the Netherlands – Pieter Geyl, Cassell History 1988

The Holy

Roman Empire – Friedrich Heer, Phoenix 1995

The Spanish

Inquisition – Henry Kamen, Phoenix 1998

Philip of

Spain – Henry Kamen, Yale University Press 1998

The Spanish

Armada – Colin Martin and Geoffrey Parker, Guild Publishing 1988

The Grand

Strategy of Philip II – Geoffrey Parker, Yale University Press 1998

Elizabeth –

Anne Somerset, Phoenix Giant 1999

William the

Silent – CV Wedgewood, Readers Union Ltd 1945

The

Hapsburgs – Andrew Wheatcroft, Folio Society 2004

[i]

William the Silent - Wedgewood

[ii]

This was revoked in the spring of 1573 in the interests of public order

[iii]

In 2014

the relative: historic standard of living value of that income or wealth is £29,510,000.00 economic status value of that income or wealth is £1,049,000,000.00 economic power value of that income or wealth is £11,170,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[iv]

The Revolt of the Netherlands - Geyl

[v]

Philip of Spain - Kamen

[vi]

Five days after the king’s sister had married King Henri III of

Navarre (the future Henry IV of France); believed to have been instigated

by the Queen Mother Catherine de’

Medici. The Huguenot nobility and upper classes had gathered for the

wedding

[viii]

Grandson of Anne of Brittany and Louis XII’s daughter Renée see Anne

of Brittany VI. Ironically Renée was a supporter of Protestantism and an

ally of John Calvin

[ix]

The massacre took place five days after the king’s sister had married King Henri III of

Navarre (the future Henry IV of France); it is believed to have been

instigated by the Queen Mother Catherine de’

Medici. The Huguenot nobility and upper classes had gathered for the

wedding

[x]

William had offered to stand proxy for the bridegroom but the incipient

invasion had led him to withdraw his offer

[xi]

One of the few Spanish senior military commanders not to emerge from the

aristocracy

[xiii]

William the Silent - Wedgewood

Finally I might be beginning to understand this war, thank you. I just bought a book in a charity shop, 'Europe Divided' by JH Elliot which I hope will also help with this very muddled and difficult period.

ReplyDelete