|

| Philip II of Spain |

The Perpetual Edict

Don Juan did not learn the lesson, ignoring the power of

the burghers his focus remained fixed on the nobility. He did however accept

the Union of Brussels, leaving William with little to rebel against. Don Juan

offered to comply with the majority of the rebel demands, but his final

intention, as evidenced in his letters to Spain, was to hand back control of

the Netherlands to Philip. Much to Don Juan’s dismay his letters were intercepted

and used as propaganda for the rebels. The Spaniards claimed them as forgeries.

Queen

Elizabeth let it be known that in her opinion William was;

‘The only man fit to be

employed in so weighty a cause; without whose assistance she cannot hope that

her affairs can take good success.’[i]

Even so Don Juan was able to pacify the delegates from the south and he signed

the Perpetual Edict of Peace on 7th February 1577. The edict was

countersigned by all the provinces apart from Holland and Zealand; Don Juan was

now the accepted Governor of the Netherlands.

Don Juan’s

finessing of the Estates General dealt with the two most important aspects of

rebel demands; he’d agreed to the removal of the Spanish troops and had agreed

that a solution to the religious question was imperative. William’s policy of

building up the power of the Estates General meant that Don Juan was dependent

on the Estates ratifying his decisions in a way no previous Governor had been.

English Support

Both the

religious question and the removal of Spanish troops from the Low Countries

were matters on which Don Juan had no intention of keeping his word. He was

surreptitiously taking control of key positions in the country. Every time he

did this William pointed this out to the Estates General and expressed his

doubts about Spanish intentions. Eventually he moved his own men into the

fortress at Gertrudenberg in the late spring of 1577.

|

| Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester |

Don Juan

immediately accused William of breaking the terms of the Pacification of Ghent.

He tried and failed to trick William, who was suffering from a tertian fever, into declaring against the Perpetual Edict. Don Juan’s

popularity turned out to be ephemeral as it became clear that he could not or

would not fulfil his promises about removing the troops and finding a solution

to the religious question. William wrote to one of Don Juan’s appointees;

‘We see now that you on your

side are not keeping faith, that not one clause of the Pacification has been

carried out, nay that you infringe it daily more and more as if it had never

been made and sworn.’[ii]

Charlotte

gave birth to her and William’s second child, Elisabeth van Nassau, on 26th April 1577. Queen

Elizabeth agreed to be her namesake’s godmother and sent presents via the Earl of Leicester who was eager to play a part in

supporting the rebels; a jewel encrusted golden dove for Charlotte and a golden

lizard for William. Elisabeth was christened on 30th May 1577 and Philip Sidney, Leicester’s nephew, stood as proxy for his uncle. And like

his uncle Sidney was an enthusiastic supporter of the rebels.

Breaking the Pacification of Ghent

I

n July

1577, following a meeting at Spa with Margot of Navarre[iii], whose brother the Duke of Anjou had his eye on the provinces for

himself, Don Juan and his troops rushed the citadel at Namur, breaking the Pacification of Ghent

as well as his own Perpetual Edict. Don Juan denounced William and the Estates

General for committing treason against Philip. The provinces rose up against

the Spanish provocation; Don Juan had failed to gauge the depth of hatred that

the Dutch had for their Spanish overlords.

_by_Nicholas_Hilliard.jpg/480px-Marguerite_of_Valois%2C_Queen_of_Navarre)_by_Nicholas_Hilliard.jpg) |

| Margot of Navarre |

The Spanish

troops were few and far between and the towns and villages rose up; Antwerp led

the way, its citizens razing the citadel. William was called south by the

Estates General and, worried about his northern provinces, he reluctantly

obliged. His former estate at Breda, stripped bare by the Spanish, was returned

to him and William started planning for Charlotte and all his children[iv], now at Middelburg, to

join him. Charlotte wrote to him of her step-children;

‘We love each other very

much and are very happy together.’[v]

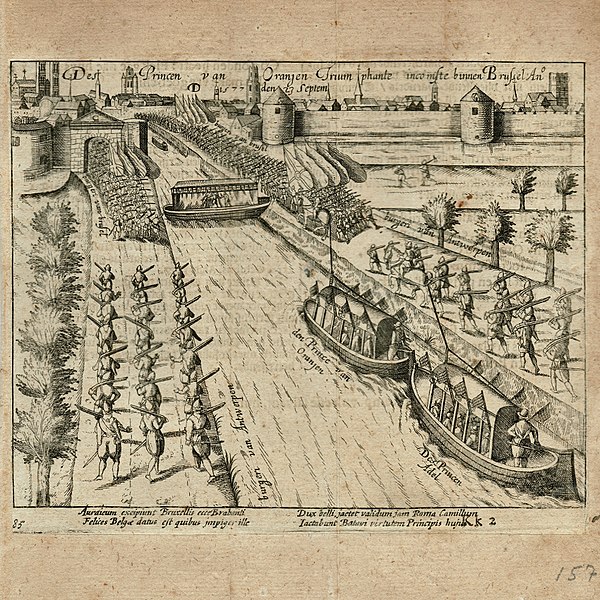

On 18th

September William entered Antwerp, surrounded by crowds of cheering citizens.

Despite being begged to stay, William made his way on to Brussels where he was

welcomed by, among others, the Duke of Aerschot and his son, both prominent

supporters of Don Juan. William once again took possession of the Palace of

Nassau, another of his properties gutted by the Spanish,

Provincial Splits

William

hoped to reconcile the northern and southern provinces in the uprising against

the Spanish crown. The northern provinces, where the Calvinists had taken

control of the machinery of government, tended towards Protestantism and spoke

Flemish, while the southern provinces remained Catholic and were Flemish or

French speakers[vi].

The south was wary of William’s Calvinism.

|

| William's entry into Brussels |

William took

his place in the Estates General and refused the offer of Governor of the

Netherlands when it was offered to him. The Estates General sent the Marquis d’Havré to England to ask for aid; Elizabeth

was most accommodating[vii]. On 29th

September she agreed to a further loan of £100,000[viii] and offered 1,000

cavalry and 5,000 foot soldiers under Leicester’s command. The Estates General

thanked her for the loan but wrote querying the wisdom of sending troops at the

onset of winter when warfare stalled.

|

| Capture of Duke of Aerschot |

Aerschot and

his fellow travellers were suspicious of William’s motives and, jealous of

William, they invited the Holy Roman Emperor’s brother Matthias[ix] to replace Don Juan as governor.

Leicester was discouraged at the splits between the rebels;

‘If they show themselves

thus irresolute, for my part I [would] rather…..abide the worst at home than

hazard life and hand with such unstable men abroad.’[x]

Aerschot,

upon being requested to restore the ancient privileges of Ghent by two

prominent citizens, immediately refused to please a crowd of ‘rascally burghers’ and claimed that he would

not do it even if the Prince of Orange supported them. The citizens of Ghent

were aroused to wrath and broke into Aerschot’s house and dragged him off and

locked him up in the citadel.

William did

not rush to have his opponent released until he’d pressured Aerschot to resign

his Stadtholdership in Flanders. But the Calvinists who replaced Aerschot as

rulers of Ghent went overboard and their punitive actions against Catholics

raised fears in the other southern provinces of the potential problems in a

joint Netherlands ruled by Calvinists.

Choices

|

| Alessandro Farnese |

Archduke

Matthias arrived in the Netherlands on 8th October 1577 and found

himself being played by William against Don Juan quartered in Luxembourg. Over

the winter it seemed distinctly possible that Philip would hand over control of

the Netherlands to his young cousin.

But William

had another possibility on hand as ruler of the provinces, the Duke of Anjou,

brother of the King of France. Catholic, vain and dishonest, Anjou could barely

have been a worse choice to rule William’s homeland.

The autumn

of 1577 saw a further 20,000 Spanish troops brought in to retaliate against the

Dutch provocation towards their Spanish rulers. They were commanded by Philip’s

nephew, Alessandro Farnese[xi], Prince of

Parma. English spies reported back home;

In view of the threat imbued by Parma, a gifted military

commander, William agreed to the easily led Matthias being made governor of the

provinces.

On 9th

January 1578 William escorted Matthias from Antwerp to Brussels and presented

him to the Estates General. William was the first of the nobles to swear

fealty. Eleven days later Parma attacked the rebels’ army camp at Gembloux while the officers were celebrating in Brussels. The resultant battle was a walkover for the Spanish and a

death knell for the rebels’ unity.

Bibliography

The Age of

Religious Wars – Richard S Dunn, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1971

The Revolt

of the Netherlands – Pieter Geyl, Cassell History 1988

The Spanish

Inquisition – Henry Kamen, Phoenix 1998

Philip of

Spain – Henry Kamen, Yale University Press 1998

The Spanish

Armada – Colin Martin and Geoffrey Parker, Guild Publishing 1988

The Grand

Strategy of Philip II – Geoffrey Parker, Yale University Press 1998

Elizabeth –

Anne Somerset, Phoenix Giant 1999

William the

Silent – CV Wedgewood, Readers Union Ltd 1945

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

Elizabeth - Somerset

[ii]

William the Silent - Wedgewood

[iii]

Wife of the future Henri IV of France

[iv]

Apart from Philip William still interned in Spain

[v]

William the Silent - Wedgewood

[vii]

It is believed that the Dutch had passed copies of Don Juan’s plans to invade

England to the English

[viii]

In 2014

the relative: historic opportunity cost

of that project is £25,400,000.00 labour cost of that

project is £331,900,000.00 economic cost of that project

is £10,120,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[ix]

Future Holy Roman Emperor

[x]

Elizabeth - Somerset

[xi]

Son of Margaret of Parma

[xii]

William the Silent - Wedgewood

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.