|

| Prince Rupert |

First Blood

A mythology

started to arise around Rupert and tales of his antics grew apace; one time in Stafford Rupert stood in the garden of a Captain Sneyd and shot at the

weathercock of St Mary’s Church. He hit it from a range of 60 yards[i] and upon Charles

dismissing the shot as a fluke Rupert repeated his feat.

Tales of his

abilities expanded to bestow on Rupert almost supernatural powers of disguise

such that he went selling apples to the Parliamentarian army. Rupert’s height,

at 6’ 4”, precluded most of the outrageous feats attributed to him. The

Parliamentarian propagandists presented Rupert as a highborn scoundrel and one

of his nicknames in the early part of the war was ‘Prince Robber’.

One task

given Rupert early on was the escorting of the silver belonging to Oxford

University to the safety of Shrewsbury. Resting at Powick bridge Rupert and his men were taken by

surprise by 1,000 Parliamentarians. Rupert led a counter charge and within half

an hour Rupert’s men had the Parliamentarians on the run. Lord Falkland wrote that;

‘Prince Maurice hath

received two or three scars of honour on his head, but is abroad and

merry……[Rupert] ventured as far as any trooper of them all’[ii]

but he was

unwounded in the fight.

Edgehill and After

|

| Lord Forth, Earl of Brentford |

The first

major set to in the war came on 23rd October 1642 at Edgehill. The Earl of Essex was the Parliamentarian commander,

known as a cuckold amongst the royalists. Rupert had already challenged Essex,

on 10th October, to a battle at Dunsmore Heath, accusing him of wanting the crown for himself.

The

royalists had originally planned to occupy Banbury on 23rd; instead they found themselves fighting Essex’ men. A

successful cavalry charge saw Rupert’s men chase their opponents off to Kineton while the foot soldiers were attacked by Essex’ reserve cavalry.

‘The King’s horse being all

gone off, his foot is charged by a part of the enemy’s horse which put them in

disorder.’[iii]

The

following day the Parliamentarians withdrew to Warwick while the royalists occupied Banbury on the 27th and made a

triumphal entry into Oxford on the 29th. The Earl of

Lindsay died during the fighting and Charles appointed Lord

Forth as his general in chief. Forth acted

as Charles chief of staff while Rupert was given the task of consolidating the

defences around Oxford and Reading. He made an attempt on Windsor Castle on 7th November and was repulsed[iv].

London in Sight

|

| Denzil Holles |

In November

Charles moved to Colnbrook and urged his nephew to attack Brentford where Rupert surprised two Parliamentarian infantry

regiments. His men pushed the forces commanded by Denzil Holles back into the town and the

Parliamentarians finally withdrew to Uxbridge under the protection of John Hampden[v] and his men. The Royalists captured 15 guns and 11

colours and about 500 prisoners, including John Lilburne who was a captain in Lord Brooke's regiment.

Afraid that

London would suffer Brentford’s fate, Rupert became the target of vicious

Parliamentarian propaganda. Lord Wharton, who fought at Edgehill, claimed

that;

‘The troops under the

command of Prince Rupert…..not only pillaged the baggage[vi]……but

killed countrymen that came in with their teams, and poor women and children

that were with them.’[vii]

|

| Lord Wharton |

Rupert was

furious at Wharton’s slanders, but they were believed by many. The

Parliamentarians used Wharton’s claims to persuade Londoners to defend their

city against the potential rampages of the Cavalier army.

Encouraged

by the victory at Brentford Charles consented to push on to London, but on 13th

November at Turnham Green the royalists met with the Earl of Essex and his army. Neither side

wanted to engage; a few cannon shots were exchanged; then Essex reoccupied

Brentford. Against Rupert’s advice Charles withdrew to Reading and returned

back to Oxford. His army was never to gain control of London.

John Gwynne,

one of Charles’ Welsh soldiers, defended Charles’ decision;

‘Nor can anything of a

soldier or an impartial man say that we might have advanced any further to the

purpose towards London than we did……the common road and other passes, were

planted with their artillery, with defensible works about them.’[viii]

No Hope for Peace

|

| Cirencester |

Between

January and April 1643 the two sides bent their efforts, conducting peace

negotiations at Oxford. The parliamentarian demands were unrealistic and

included Charles getting rid of the bishops and demobilising his army, along

with handing over his key supporters to Parliament for punishment.

As the talks

dragged on Rupert remained on the offensive. In February Rupert attacked Cirencester[ix] with 6,000 men. It took four hours

to capture the town which refused an offer to surrender. Once again false

propaganda dogged Rupert; the stories emanating from London claimed that Rupert

sanctioned the murder of Puritan ministers and women and children.

|

| Lord Denbigh |

Rupert

overcame a Parliamentarian force at Alton in Hampshire in late February before attacking the enemy in

Wiltshire; speed and surprise the essence of his attacks. Henrietta Maria

landed in Yorkshire on 22nd February, bringing reinforcements and

much needed armaments from the continent. Rupert was sent with 12,500 men to clear

a route for the queen through the hostile midlands.

Rupert took Birmingham[x] on 3rd April;

‘The Prince took Birmingham

by assault with little loss, only the Lord

of Denbigh[xi] was

unfortunately slain.’[xii]

The

opposition claimed that Rupert’s men defiled the women of Birmingham and set

the town ablaze[xiii].

By the middle of the month he’d taken Lichfield, occupied by Parliamentarians.

More Victories

|

| Earl of Essex |

In Rupert’s

absence the Earl of Essex laid siege to Reading and Rupert was ordered back to

Oxford. By the time Charles and Rupert met at Caversham. Reading had fallen to the

opposition. Outnumbered the deputy governor Sir Richard Fielding surrendered

and he and his men marched out of the town. Fielding was court-marshalled and

sentenced to death; at Rupert’s intervention Fielding was taken down from the

scaffold.

Essex then

took Thame and sent an advance guard to Wheatley, only five miles from Oxford. On 18th

June the two armies met at the battle of Chalgrove Field. Rupert was chasing after a convoy

escorting a large sum of money to Thame. Following a daring leap over a hedge

by the Rupert’s cavalry the Parliamentarians fled and John Hampden was mortally

wounded.

Essex

withdrew to Aylesbury while Rupert established himself at Buckingham, forcing Essex to draw back to north Bedfordshire.

Rupert’s victories meant safe passage for Henrietta Maria to join Charles at

Edgehill. A week after Henrietta Maria’s return Rupert set off with a large army

intending to take either/or Bristol or Gloucester, clearing the route to Wales.

Rupert’s

road was clear as Ralph Hopton had taken much of the south west

with three battles at Stratton, Landsdowne and Roundway Down. Maurice took part in the battle of

Roundway Down and General Waller was comprehensively defeated,

retiring to Gloucester with the rump of his forces.

|

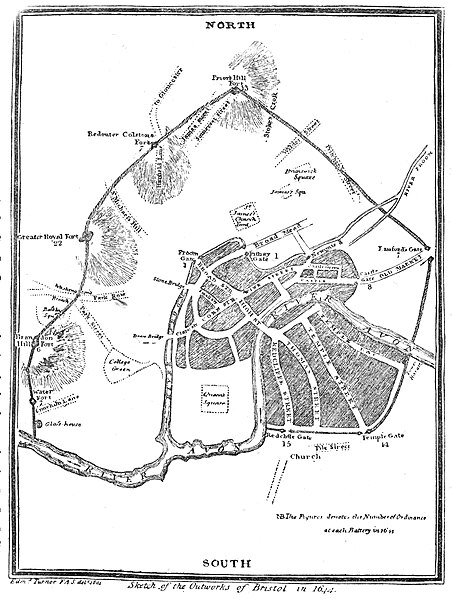

| Bristol outer defences |

As Waller

was now ensconced in one of his objectives, Rupert chose to attack Bristol, the

second largest port in the country. On 25th the Cavalier army attacked the town defended by a force under Sir Nathaniel Fiennes,

an amateur soldier. Rupert’s horse was killed under him during the fighting.

‘His Highness having

recovered another horse, rode up and down from place to place, here directing

and encouraging some, and there leading up others; generally it is confessed by

the commanders that had not the Prince been there, the assaults, through mere

despair, had been in danger of being given over in some places.’[xiv]

Fiennes

surrendered and looting of the town started, which Rupert tried to prevent.

Fiennes recorded that Rupert and Maurice;

‘Did ride among plunderers

with their swords hacking and slashing them.’[xv]

Rupert

apologised for failing to control his men. Always indecisive, Charles had

already charged Rupert with returning a large part of his cavalry as Essex had

returned to Aylesbury. But learning of his nephew’s success at Bristol, Charles

decided to journey there himself intending to attack Gloucester.

The

relatively inexperienced Maurice[xvi] was placed in charge of

the army in the west, replacing the Marquis of Hertford, while Rupert was

ordered to increase funds and recruit more men.

Bibliography

Prince

Rupert of the Rhine – Maurice Ashley, Purnell Book Services Ltd 1976

The English

Civil War – Robert Ashton, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1989

The Memoirs

of Elizabeth Stuart Vol 1-2 – Elizabeth Benger, General Books LLC 2012

Charles the

First – John Bowles, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 197529th.

Charles I –

Christopher Hibbert, Penguin Books 2001

The Civil

Wars of England – John Kenyon, George Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1989

Prince

Rupert of the Rhine – Patrick Morrah, Constable & Company 1976

The English

Civil War – Diane Purkiss, Harper Perennial 2007

Prince

Rupert – Charles Spencer, Phoenix Paperback 2008

[i]

A prodigious feat with the unreliable firearms of the time

[ii]

Prince Rupert - Spencer

[iii]

Rupert of the Rhine - Ashley

[iv]

The castle was the Parliamentarian military HQ throughout the war

[v]

Cromwell’s cousin

[vi]

Wharton was not averse to pillaging on his own behalf

[vii]

Prince Rupert - Spencer

[viii]

The English Civil War - Purkiss

[ix]

Which housed a large Parliamentary garrison

[x]

A centre of arms manufacture

[xi]

His son fought on the Parliamentarian side

[xii]

Prince Rupert - Spencer

[xiii]

Birmingham was burnt against Rupert’s wishes

[xiv]

Rupert of the Rhine - Ashley

[xv]

Ibid

[xvi]

He had hitherto only commanded cavalry

Definitely one of those larger than life characters who manages to look dashing even in the horrid short-waisted jerkins that were fashionable and make all the men look pregnant.

ReplyDelete