|

| Mary, Duchess of Richmond |

The Enemy Within

Rupert

was feared and the Parliamentarians found him odious; they made good use of PR,

with leaflets circulating cataloguing his crimes. They painted him as sexually

incontinent and accused him repeatedly of having a love affair with Mary[i], Duchess of Richmond,

the wife of his closest friend[ii]. Mary

and her husband James

were Rupert’s staunch supporters at court, protecting him against the

infighting of less favoured of Charles’ courtiers.

As

the war progressed Rupert found it ever more difficult to fight for a cause

wherein he found so many of the protagonists unsympathetic. Rupert loathed men

like Digby, Wilmot and Goring and he found himself

opposing the queen’s rigid sense of right and wrong.

|

| Bristol Castle |

Three

Parliamentarian peers, the earls of Bedford, Clare and Holland, came to Oxford to beg

forgiveness from Charles for fighting against him. Henrietta Maria told her

husband to send the men back to the Parliamentarians; there should be no pardon

for those who dared to rise up against their monarch.

Rupert

was more pragmatic; pardoning the three men would reduce the numbers supporting

the enemy and hopefully induce more men to cross the divide. Charles agreed

with his nephew and pardoned the earls, upsetting his wife. Rupert had used up

most of his goodwill with the royal couple; Charles was very reliant on

Henrietta Maria who was not a fan of Rupert’s.

Following

the fall of Bristol Rupert was awarded the governorship of the city. His

enemies within the Royalist camp backed the Marquess of Hertford’s

recommendation to give Sir Ralph Hopton the prize in return for his three

victories. Charles was in a quandary, writing to Hopton;

‘We too much

esteem our Nephew P. Rupert, to make him a means of putting any disrespect upon

any Gentleman, especially one we esteem so much as you, than to give you any

distaste.’[iii]

Rupert

was allowed to remain governor, while Hopton was made his deputy; secretly Rupert

allowed Hopton to govern the city as he saw fit.

Gloucester and More

Charles

moved his army to Gloucester and told Rupert to demand the city’s surrender

from the rebel commander, Colonel Edward Massey[iv]. Massey refused and the

army set down to besiege the town. Rupert was not convinced of his

uncle’s strategy, believing that it might be prudent to skirt the town and move

onwards towards London.

|

| Queen Henrietta Maria |

Henrietta

Maria blamed Rupert because her husband went to Gloucester with his army; she

believed Rupert was stopping Charles returning to London. Henrietta felt

isolated alone in her lodgings at Merton College, Oxford and was hurt by

her impeachment on 21st June. Like Rupert she was very unpopular,

not least for her religion, to which the queen hung as a lifeline. She saw it

as her duty as a good Catholic to try and save those around her; something

which had disastrous results.

A

poor influence on her husband Henrietta Maria was also vilified by the

Parliamentarian broadsides;

‘Who went to the

Brokers with the Jewels of the crown, and the cupboard of gold plate? Who

bought pocket-pistols, barrels of powder, and many such pretty toys to destroy

the Protestants Was it Queen Mary? The very same.’[v]

Gloucester

remained defiant and the siege was not lifted until early September when the

Royalists learned that the Earl of Essex was en route to relieve the town with

an army of 14,000. Rupert tried pressed an attack on the relief army at Stow-on-the-Wold, but was repulsed.

Essex

slipped into Gloucester and managed to persuade Charles that he intended to

return to London via Worcestershire. Charles obligingly moved his army to Evesham and Essex moved quickly over to Cirencester and retook the

town Rupert has taken earlier in the year. Essex then began his return journey

to London. Rupert caught up with the Parliamentarians at Aldbourne Chase[vi] but was beaten off.

Rupert’s troops sped to reach Newbury first and occupied the town.

Newbury and Beyond

|

| Newbury and surrounding countryside |

Charles

brought up his army to Newbury and resolved to fight the next day; 20th

September. His optimism was reinforced by the arrival of fresh troops from

Oxford. The battle on the morrow resulted in a

conclusive victory for Essex, who was aided by the opposing side’s shortage of

ammunition[vii]. Rupert’s cavalry were

hampered by the hedges and hillocks around the site of the battle.

‘The Earl of Essex did break

both the head and the heart of the King’s Army at Newbury.’[viii]

Rupert had

opposed the fighting, knowing the problems his men faced and aware that Essex’s

men would make the most of the terrain. The battle was one of the turning

points of the war and Charles would never again be in a position to defeat the

opposition in the field and give himself a clear run on London.

|

| Donnington Castle |

Charles lost

a number of good men in the fight including Caernarvon, Falkland[ix] and Sunderland. Essex’s

army moved off, marching towards London. Rupert and his men harassed the line

of march but were checked three miles from Newbury by Parliamentarian

musketeers.

Charles

ordered Rupert to garrison Donnington Castle, and then he and his nephew returned to Oxford. Ten

days later the indomitable Rupert was off to seize Bedford. En route he and his men took Newport Pagnell where Rupert placed Sir Lewis Dyve [x]in charge. At the end of

October, after a muddle over ammunition, Dyve withdrew from this key position

allowing Essex to occupy the town. Rupert now suggested an attack into East

Anglia which was shouted down by his enemies, as being high-risk, which it was

despite the pockets of Royalist support in the area.

Late in the

year Rupert’s brother, Charles Louis, visited London to pledge his support for

the Parliamentarians, who promptly reinstated his pension. The Protestant

supporters of the ousted Elector were unhappy that Rupert and Maurice were

fighting against the Puritan Parliament. Charles Louis himself strongly

believed that regaining the Palatinate was a duty that overrode his duty to his

uncle; Parliament believed that Charles Louis’ cause was a Protestant crusade.

Disaster Looms

|

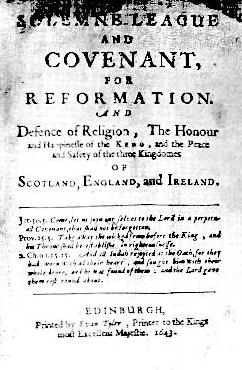

| Frontispiece Solemn League & Covenant |

In the late

autumn the Parliamentarians and the Scots came to an agreement, signing the Solemn League and Covenant. The Scots agreed to invade; to

counter this Charles decided to bring back his troops stationed in Ireland.

Rupert pushed to be given command of the influx of soldiers, chafing against

the intrigues in Oxford. One of his supporters wrote;

‘The army is much divided

and the Prince at true distance with many of the officers of the horse.’[xi]

The gulf

between Henrietta Maria and Rupert was widening, but Charles made Rupert a peer

on 23rd January 1644; Earl of Holderness and Duke of Cumberland. By this time the Scots had already invaded and the

Royalist army in the north was trounced by Sir Thomas Fairfax[xii]. Convinced that the north was to be

where the action was Rupert got himself made Commander of Chester, Lancaster,

Worcester, Salop and the northern counties of Wales.

Rupert set

off north on the 6th February where the Marquess of Newcastle’s army, east of the Pennines, was exposed to attack from the Scots and from a Parliamentarian

northern army. Rupert needed to provide cover for them as well as ensure the

safety of Oxford which was under constant pressure from Essex’s men. Rupert

spent much of the summer of 1644 riding between the two.

Parliament

decreed that Charles’ Irish troops were to be executed once captured. Thirteen

of Rupert’s men were hanged near Nantwich, classified as Irish

Papists although all of them were English. In retaliation Rupert executed

thirteen of the enemy, promising thereafter to kill two Parliamentarians for

every one of his men executed. His threat stopped further retaliation.

In Oxford the

anti-Rupert cabal of Digby, Wilmot and Percy was joined by Sir John Culpeper; they increasingly had the ear of the

king, despite their joint lack of military expertise. Rupert’s relief of Newark[xiii] was a counter to their whisperings.

Newcastle wanted Rupert to remain in the northern Midlands, but the exigencies

of war required him to recruit in the Welsh Marches. In his absence Lincolnshire was taken and Lord Bellasis’ army was defeated at Selby.

Bibliography

Prince

Rupert of the Rhine – Maurice Ashley, Purnell Book Services Ltd 1976

The English

Civil War – Robert Ashton, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1989

Charles the

First – John Bowles, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 197529th.

The Diaries

of Lady Anne Clifford – DJH Clifford (ed), Alan Sutton Publishing Ltd 1990

Charles I –

Christopher Hibbert, Penguin Books 2001

The Grand

Quarrel – Roger Hudson (ed), Folio Society 1993

The Civil

Wars of England – John Kenyon, George Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1989

Prince

Rupert of the Rhine – Patrick Morrah, Constable & Company 1976

The English

Civil War – Diane Purkiss, Harper Perennial 2007

Prince

Rupert – Charles Spencer, Phoenix Paperback 2008

[ii]

There is no evidence that the relationship was anything other than platonic

[iii]

Prince Rupert - Spencer

[iv]

Later to change sides and fight for Charles II

[v]

The English Civil War - Purkiss

[vi]

Near Swindon

[vii]

Ammunition could have been fetched from Oxford but Charles was not prepared to

delay

[viii]

Prince Rupert - Spencer

[ix]

One of Charles’ two Secretaries of State, Falkland was fighting in a conflict

he abhorred; he was replaced by Rupert’s enemy Lord Digby

[x]

One of Lord Digby’s stepbrothers

[xi]

Prince Rupert - Spencer

[xiii]

A staging post between Newcastle’s army and Oxford

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.