|

| Carolingian currency |

Attack is the Best Form of Defence

Charles’

return to his kingdom was predicated by the need to deal with the Saxons who

were once again causing problems. Charles was a ruler able to view events on a

long term basis; he realised that in order to stabilise his northern borders

the regions to the north needed pacifying. In 776 he began construction of a

fortress at Paderborn[i], near the source of the river Pader,

deep inside territory formerly belonging to the Saxons.

In 777

Charles held his spring review with his nobles amid the construction site that

was Paderborn. His standing was increased by the attendance of an envoy from Al-Andalus seeking Charles’ assistance. Charles was becoming a

personage, a counter to the power of Constantinople.

One of the

most formidable of the Saxon warriors was a champion named Widukind. He was to be a thorn in the Frankish side for many years, conducting

raids into Francia and then retreating into the marshes of his homeland or into

Nordmannia or Frisia. While not very competent militarily Widukind was a hero to his people

and helped stiffen resistance to the invading Franks.

|

| Frisia |

In 779 the

campaigning season took the Franks to the Saxons’ northern border with the

Slavs. The East Saxons put up little resistance and there were mass conversions

to Christianity. According to Einhard;

‘Sometimes they were so

cowed and broken that they promised to abandon the worship of devils and

willingly to submit themselves to the Christian religion.’[ii]

Charles

established churches and monasteries in the newly captured lands in an attempt

to encourage the unconverted to see the light[iii].

The Saxons’ resolve and their ability to field armies season after season

remained undiminished, an annual drain on Charles’ finances. Both sides lost

thousands of fighting men and the line between the two territories was very

fluid and varied from season to season.

Campaigning in Spain

|

| Umayyad Caliphate in 750 |

Charles’

expedition into Islamic Spain in 778 was encouraged by Pope Hadrian who wanted

to expand Christian influence throughout the peninsula and eliminate the Muslim

presence[iv].

The Muslims in the western Mediterranean were in disarray following the

overthrow of the Umayyad Caliphate by the Abbasids. In Spain Abd al-Rahman I[v] resisted the Abbasid revolution and

instituted an independent caliphate with a capital in Córdoba.

Abd

al-Rahman was opposed by supporters of the Abbasids, religious dissidents and

local leaders bidding for independence. Sulaiman ibn Yaqdhanu’l-A’rabi, the wali of Barcelona, headed the opposition which included a number of Muslim princelings

holding sway over the lands between the Ebro and the Pyrenees. Those opposing Al-Rahman sent

envoys to Paderborn, calling on Charles for assistance to rid them of this

interloper.

Charles led

an army into Islamic Spain where he was able to take Pamplona, a city damaged by earlier internecine wars. He then marched on to Zaragoza while a second army travelled to Barcelona. The garrisons of both cites refused to admit their nominal allies, the

Franks. Sulaiman had been murdered by one of his colleagues and the

anti-al-Rahman clique fell into disarray. Al-Rahman marched northwards sweeping

the rebels before him and Charles had no option but to retreat homewards.

Einhard

tells a different story. According to him;

‘Charles attacked Spain with

the largest military expedition that he could collect. He crossed the Pyrenees,

received the surrender of all the towns and fortresses that he attacked.’[vi]

Charles may have

felt pressured into accepting the rebels’ invitation in order to match the

reputation of his grandfather Charles Martel who, in 721, who pushed the

Muslims out of Aquitaine and back over the Pyrenees[vii].

|

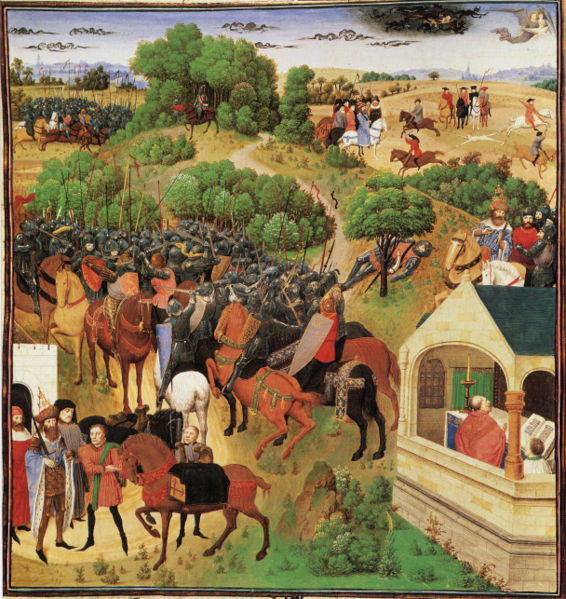

| Battle of Roncevalles |

It was at

the end of this Spanish campaign that Charles suffered his greatest defeat,

glorified in the Chanson du Rolande written in the 11th century. The original

crossing into al-Andalus over the Pyrenees had made enemies of the Gascons

living in the mountains, they objected to the taking of Pamplona. On the

Frankish army’s return to Francia, circa 15th August, the Gascons

attacked at Roncevalles.

Einhard

records that the dastardly Gascons attacked the Frankish army marching enfilade

through the narrow valleys, at the battle of Roncevaux Pass.

‘For while his army was

marching in a long line….the Gascons placed an ambuscade on the top of the

mountain….and then rushing down into the valley beneath threw into disorder the

last part of the baggage train and also the rearguard which acted as a

protection to those in advance. In the battle which followed the Gascons slew

their opponents to the last man.’[viii]

One of

Charles’ captains, Roland died during the battle, along with a

number of Charles’ friends and leading nobles. The humiliation of this defeat

did not lower Charles’ standing in Francia.

Charles’

southern frontier was safe from attack as successive caliphs were too involved

in internal problems to worry about expanding the caliphate northwards. The

Christian kingdoms of Asturias, Navarre, Leon, Castile and Aragon were a buffer

zone between Charles’ lands and al-Andalus.

Massacre at Verden

Charles was

caught in a fight to the death with his neighbours, having staked his

reputation as a leader on the fight. His treatment of the Saxons, who would not

give way, became ever more savage. Failing to conquer all of Saxony would

deleteriously affect the cohesion of the Franks who were drawn on by the

promise of riches.

In 782 the

majority of Saxon leaders, bar Widukind, capitulated to the Franks. Charles

then enforced a number of constraints on the Saxons; making it illegal to

destroy or raid churches, kill priests or refuse baptism. He also imposed military

service on the Saxons to take the fight to the Slavic tribes on the northern

borders. In retaliation Widukind rallied his fellow Saxons and rose up against

the Franks. By the spring of 783 the uprising was widespread.

|

| River Aller |

Three of

Charles’ captains precipitately led the Frankish army into the battle of Süntel and lost most of their men including

two of the three captains and two Counts. From his base in Auxerre Charles led a second army into Saxony and summonsed the Saxon leaders to

resubmit themselves to his authority. Widukind fled yet again and his fellow

leaders surrendered the warriors who fought in the battle. Charles authorised the massacre of the 4,500 Saxons[ix]

at Verden, beheaded near the river Aller. The Royal Frankish Annals comments;

‘The Lord King Charles

rushed to the place with all the Franks that he could gather on short notice

and advanced to where the Aller flows into the Weser.

Then all the Saxons….surrendered the evildoers who were chiefly responsible for

this revolt to be put to death—four thousand and five hundred of them. This

sentence was carried out. Widukind was not among them since he had fled to

Nordmannia.[x]

Trouble Abroad

|

| Ardennes |

Even the

massacre did not stop the fighting; Charles had to campaign in 783 and 784 and

beyond. Charles was aware that Widukind was a voice that needed silencing. In

785 Charles offered Widukind safe passage to his villa[xi]

at Attigny in the Ardennes. The two men met there in the autumn where Charles showered

his visitor with gifts and a pardon in return for which Widukind was baptised

on 25th December with Charles standing as his godfather.

The

conversion of this renegade did not mean an end to the fighting which continued

sporadically until 805. Charles arranged the government of Saxony, less as a

colony, more an integral part of his kingdom leaving him free to concentrate

his attention elsewhere.

Alongside

the later campaigns against the Saxons Charles was having problems ruling his

lands in Italy. The distances between his capital and Lombardy meant that

Charles could not provide speedy decisions for problems emanating from Italy.

The independence of Spoleto and Benevento were thorns in the side of the papacy while Benevento remained good relations

with Byzantium[xii]

which regarded it as a client state in the west.

Joining East and West

|

| Constantine VI with his father Leo IV |

The eastern

empire was undergoing its own woes with the Iconoclastic Controversy[xiii]. In both east and west there were Islamic states pressing for further victories, while only Charles was extending

Christianity in the north. This role increased Charles kudos as a

counter-balance to Byzantium, making his support ever more attractive to the

pope.

In 781 the

Byzantine Empress Regent Irene began negotiations with Charles for

Rotrude to marry her son Constantine VI. Irene went as far as to send an official to instruct Rotrude

in Greek; but in 787 Irene broke off the engagement against her son's wishes[xiv].

Irene demanded that Rotrude be sent to Constantinople and Charles refused,

breaking the agreements between the two empires.

Irene had

looked for Charles support for the restoration of the practise of venerating

icons, but events conspired against her. Constantinople had provided a safe

harbour for Desiderius’ son Adelchis and Irene refused to return him. And

Hadrian had no desire to see a rapprochement between the major powers in the

west the east; he preferred to be a pivot between the two.

In

retaliation to the breakdown of the agreement in 788 Irene sent an army into

Italy, headed by John the Military Logothete, The army was aided by the Byzantine

Governor of Sicily, Theodore. The Byzantines aimed to occupy Benevento, but the

citizens, aided by the Lombards, fought off the invaders who retreated

ignominiously.

Bibliography

Celts and Saxons – Peter Berrisford Ellis, Constable and Company Ltd

1995

The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages – Robert Fossier

(ed), Cambridge University Press 1989

The Oxford History of Medieval Europe – George Holmes, Oxford University

Press 2001

The Year 1000 – Robert Lacey & Danny Danziger, Abacus 2007

Absolute Monarchs – John Julius Norwich, Random House 2011

Emperor of the West – Hywel Williams, Quercus 2010

Charlemagne – The Great Adventure – Derek Wilson, Hutchinson 2005

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

He may have intended Paderborn to be his new capital

[iii]

There may very well have been many instances of forced conversions

[iv]

Something not achieved until the Reconquista ended in 1492;

see http://wolfgang20.blogspot.co.uk/2015/11/renaissance-europe-juana-la-loca.html

[ix]

The figure is disputed

[xii]

Byzantium also owned lands in southern Italy

[xiii]

The first of two disputes in part over whether religious pictures should be

shown in churches

[xiv]

Increasing enmity between mother and son

Ah bribe the enemy into submission... he should have thought of it earlier though

ReplyDelete