|

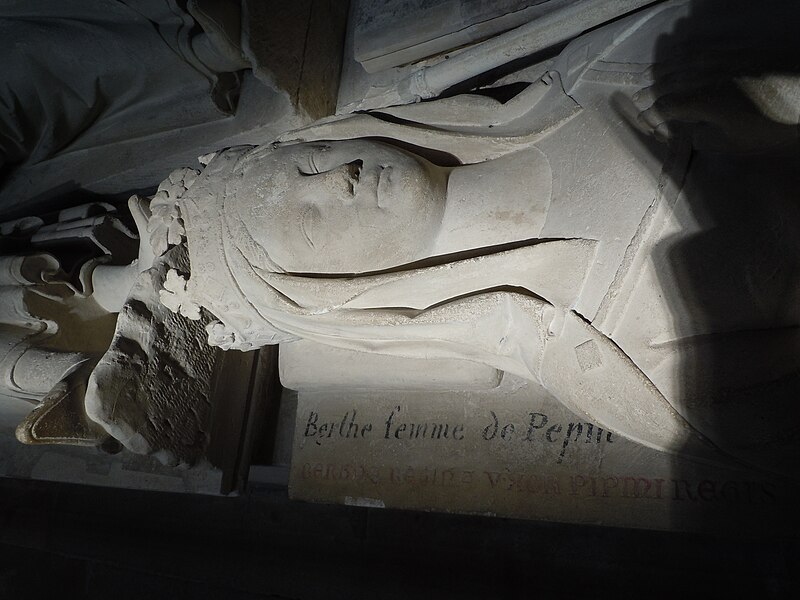

| The tomb of Bertrada of Laon |

Charles’ Family

On 30th

April 783 Hildegard died[i]

at Thionville in the same year that her daughter

Hildegarde died. Bertrada of Laon died in the summer and Charles buried his

mother next to his father in the basilica of St Denis.

‘Bertrada died after the

death of Hildigard, having lived to see three grandsons and as many

granddaughters in her son’s house. Charles had his mother buried with great

honour in the same great church of St Denys in which his father lay.’[ii]

Charles

married his third wife Fastrada in 784 and she had a daughter Theodrada[iii]; her second child was Hiltrude born

in 787.

Despite

close chaperonage Charles’ daughter Rotrude had an affair with Rorgon[iv], and in 800 had a son named Louis. There was talk that Bertrada might

be married off to King Offa of Mercia. Instead she had a long and

passionate affair with one of her father’s closest friends, Angilbert[v], a courtier, warrior, poet, scholar

and religious leader. There is dispute over whether the couple were married,

but they had two sons, one of them Nithard, born in 795, became a historian. Once Angilbert, when he was away on

official business, wrote a poem he sent to Bertrada, referring to the couple’s

children;

|

| Charles with his son Louis |

‘Tell the boys, poem of

mine, to keep safe by God’s mercy within their walls from fire and thief and

sickness.’[vi]

Charles did

not approve marriages for any of his daughters[vii];

instead they were placed into positions of power within the church as Abbesses. Their illegitimate children were provided for in the same way.

In 781

Charles had his son Carloman (whom he had renamed Pepin) anointed "king of

Italy" and crowned by Hadrian with the Iron Crown of Lombardy. Pepin’s

younger brother Charles was anointed king of Aquitaine. Charles’ youngest son Louis,

who was only 3-years old, was appointed sub-king of Italy and Aquitaine.

Educating Francia

|

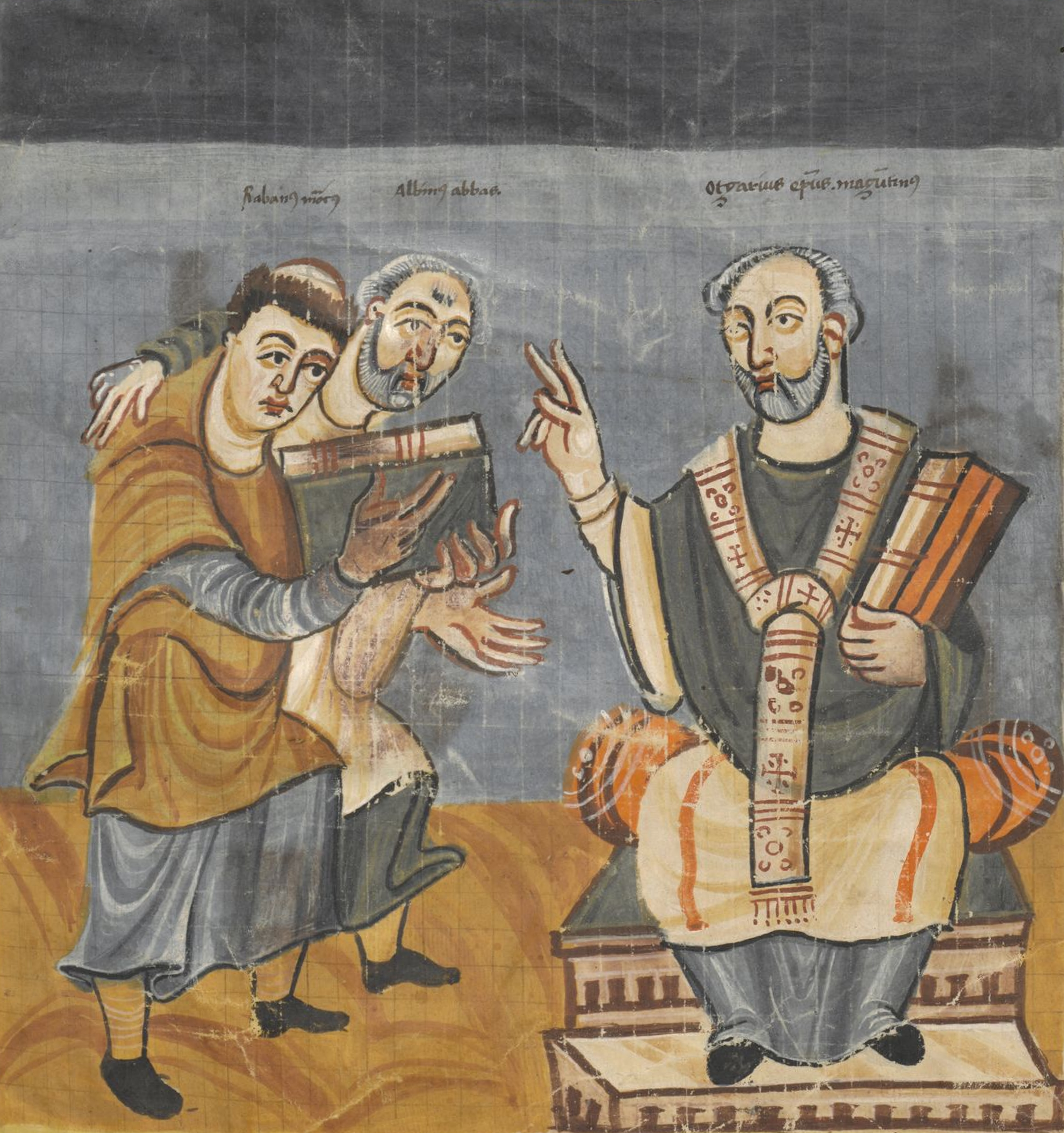

| Alcuin of Northumberland |

From the

very beginning of his reign Charles had plans for role of education in Francia.

The French politician and historian François Guizot[viii] said of Charles;

‘His predominating idea was

the design of civilising his people.’[ix]

Charles had

grown up in his father’s sophisticated court where he met many of the premier

prelates of the day.

Charles and

his advisers were concerned to rule Francia in accordance with God’s will. And

for that the clergy needed educating. A series of Capitularies decreed the

restoration of strict canon law in the church, conformity of rule in

monasteries and correct Christian

living throughout the kingdom.

In 782

Charles invited Alcuin of Northumbria[x] to join his court. Charles’ sister

Gisela was an active supporter of Alcuin’s work. Alcuin was to play an important

role in Charles’ cultural and religious ambitions. He ran the palace school for

14 years, where the sons of kings and princes and the nobility came to be

instructed in the trivium

and the quadrivium[xi]. To provide the school with texts

Charles had agents scouring libraries for interesting manuscripts which were

copied in his ever busy scriptoriums.

Charles was

fascinated by astrology almost as much as he was by the bible and the heads of

the early church. According to Einhard;

‘[Charles] paid the greatest

attention to the liberal arts….For his lessons in grammar he listened to the

instruction of Deacon Peter of Pisa, an

old man; but for all other subjects Albinus, called Alcuin, also a deacon, was

his teacher…. the most learned man of his time. Charles spent much time and

labour in learning rhetoric and dialectic, and especially astronomy, from

Alcuin.’

Peter of

Pisa not only taught Charles grammar, he also taught him Latin, the language of

the church. Charles efforts to improve his reading and writing came to naught,

despite keeping notebooks under his pillow to enable him to work in snatched

moments of free time.

Bavarians

|

| The Tassilo Cup |

Duke Tassilo of Bavaria, a cousin of Charles and son-in-law

of Desiderius, asserted his independence of the Franks. Both Pepin the Short

and Charles took the view that Bavaria was a vassal state. Tassilo occasionally

provided troops for Charles’ armies, but occasionally declined to attend the

annual gatherings of Frankish nobles. In 781 Hadrian told Tassilo to;

‘Remember his former oaths

and not to go back on his long-standing pledge to the Lord King Pepin, the

great Lord King Charles and the Franks.’[xii]

Hadrian’s

poking his nose into this squabble probably resulted from Tassilo’s

interference in church affairs in Bavaria, deeply resented by the bishops

there. In a separate decision, that doomed Tassilo, Charles decided that he

needed direct control over the eastern Alpine passes and the Danube valley[xiii].

Hadrian

assisted Charles in putting pressure on Tassilo and when Tassilo sent envoys to

Rome in 787, he pronounced an anathema on Tassilo. Charles ordered Tassilo

to present himself at Worms and ratify an oath of loyalty, a journey Tassilo

was reluctant to undertake.

|

| Charles' villa at Engelheim |

Charles

reacted by sending three armies into Bavaria; he led the army that crossed the

Danube near Regensburg. Another army under Pepin’s titular

leadership crossed the Alps from Italy. Tassilo had no choice but to surrender

his lands to Charles. He was allowed to yield up his dukedom, but within months

was charged with plotting rebellion with the Avars in the lands bordering Bavaria.

Tassilo, his

family, treasure and household were taken to Charles’ villa at Engelheim and there was tried and convicted after he confessed. Tassilo and his sons were

forcibly tonsured and sent to separate monasteries, while his wife was exiled.

For his part Hadrian’s problems in Italy were lessened

when, on 26th August 787, Arechis II, Duke of

Benevento, died. His son Grimoald III, was a hostage

of the Franks. In 788 Charles’ son Charles the Younger made Grimoald a client

of the Frankish kingdom.

And Barbarians

| Abrodites' territory |

In 789

Charlemagne marched an Austrasian-Saxon army across the Elbe into Abodrite territory. The Slavs ultimately

submitted, led by their leader Witzin. Charles accepted the surrender of

the Wiltzes under Dragovit demanding hostages. Charlemagne insisted on the right to send missionaries

into the area and that they not be molested. The army marched to the Baltic before turning around and marching

to the Rhine. The army returned home with a large amount of booty that had been

easily won. The tributary Slavs became loyal allies.

Following

the campaigns in the north Charles turned his attention to the Avars, a tribe

centred in the Lower Danube basin. By early 7th century they

dominated the area[xiv].

Their dominancy was threatened by the Bulgars who forced the Avars westwards towards Bavaria[xv].

In 791 the Avars raided into Bavaria and when they were repulsed offered

hostages and conversions.

Charles

decided to personally see off the Avar attack. At the head of a large army,

before crossing into enemy territory, Charles ordered three days of prayer and

fasting to ensure divine aid. The opposition crumbled; allowing the Franks to

strike deep into Avar territory. The Avars had been weakened by the Bulgars and

internal strife.

|

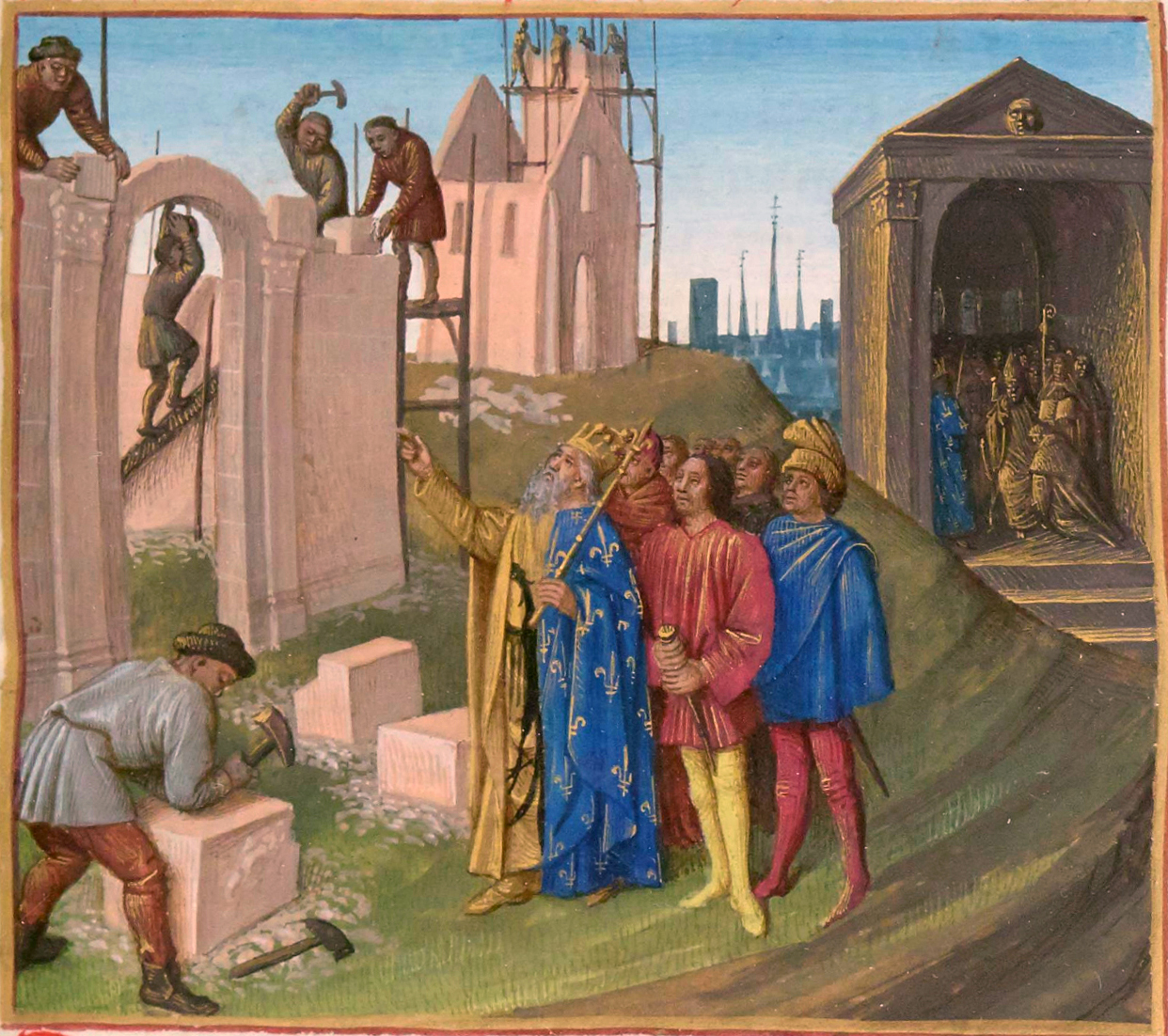

| Charles inspecting the work on his palace at Aachen |

The Royal

Frankish Annals record that;

‘[Duke Erik]

dispatched his men under the command of the Slav Wonomir into

Pannonia and

had them plunder the ring[xvi]

of the Avars…..the duke sent the treasure of the ancient kings[xvii]….to

the Lord King Charles at the palace at Aachen.’[xviii]

Charles

donated part of the haul to the pope and gave rewards to his counts and dukes. But

much of his prize was devoted to building himself a new capital city at Aachen[xix].

The architect whose job it was to create Charles’ vision was Odo of Metz, responsible for the palace Charles built there.

The

expeditions against the Avars secured Charles’ eastern borders, although he

made no effort to include the Avar territory in his kingdom. The marches of the

Danube provided a buffer zone between Francia and the Balkans with whose tangled affairs Charles had no desire to involve himself in.

Bibliography

Celts and Saxons – Peter Berrisford Ellis, Constable and Company Ltd

1995

The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages – Robert Fossier

(ed), Cambridge University Press 1989

The Holy Roman Empire – Friedrich Heer, Phoenix 1999

The Oxford History of Medieval Europe – George Holmes, Oxford University

Press 2001The Year 1000 – Robert Lacey & Danny Danziger, Abacus 2007

Absolute Monarchs – John Julius Norwich, Random House 2011

Emperor of the West – Hywel Williams, Quercus 2010

Charlemagne – The Great Adventure – Derek Wilson, Hutchinson 2005

www.gutenberg.org

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

Possibly worn out by birthing nine children

[iv]

Later the Count of Maine

[v]

Made a saint

[vi]

Charlemagne - Wilson

[vii]

It has been postulated that Charles was concerned about setting up potential

rivals

[ix]

Charlemagne - Wilson

[xi]

Together these made up the seven liberal arts

[xii]

Charlemagne - Wilson

[xiv]

In 626 they even threatened Constantinople and only their lack of sophisticated

siege weapons halted their attack

[xv]

In turn the Bulgars were being ousted by the Byzantines who were reasserting

control over former possessions.

[xvii]

So much treasure was held in the ring that Charles sent a second expedition

under Pepin to retrieve the remainder

[xviii]

Charlemagne - Wilson

[xix]

Popular with the Romans for it’s hot springs

I note that you mention that Charles was fascinated by Astrology but that Einhard says that he studied Astronomy. I know that the two were much the same then, but Astronomy implies an interest in the heavenly bodies for their own sake, or to use for navigation, where astrology implies fortune telling and so on. This is an interesting dichotomy in his character if so, since the only time the readers of stars and portents were mentioned in a positive light were the Magi who came to Bethlehem to worship the King whose star had arisen. Other astrologers in apocrypha[which hadn't all been separated off at this date] and in the Bible, such as Simon the Wizard,[Acts? I think] were shown to be frauds. I'm not sure I'm drawing any conclusions here, just fishing in the dark around an interesting paradox.

ReplyDelete