|

| Oudenaarde |

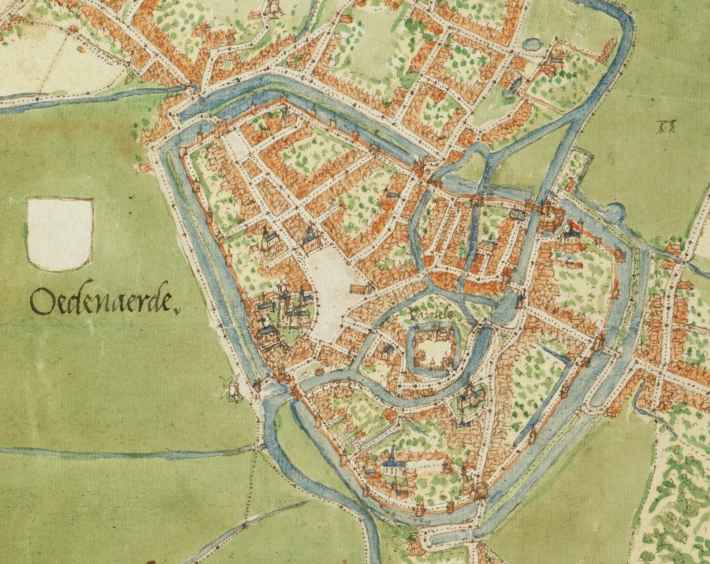

Philip resolved

on military intervention in Ghent; he was no longer prepared to allow the

townspeople to run his town as they felt fit. He declared war in a letter dated

31st March 1452 and upon receiving it the captains of Ghent

organised a procession through the town. At the same time they sent an embassy

to Philip composed in the main of churchmen.

On 7th

April Ghent occupied Philip’s castle of Gavere and a week later the civic militia, led by one of the three captains,

Lievin Boone, attacked and besieged Oudenaarde[i]. Simon de Lalaing, one of Philip’s captains, led the defence. Messages

were shot into the town for the edification of the townspeople trying to divide

them from Philip’s men. The messages;

‘Requested and urged the

said Sir Simon to surrender and deliver up the town on the day he had fixed

with them and stated that the money they had promised him was all ready.’[ii]

Philip sent

two armies to the relief of Oudenaarde, one of them led by his cousin Jehan de

Bourgoyne, By May Philip’s armies were attacking Ghent and on 16th

June the Ghent army was tempted away from their fortified lines at the battle

of Bazel where the favourite of Philip’s

bastard sons, Corneille, was killed[iii]. His was the only death

from the duke’s forces while 1,500 Ghenters died. Philip and his heir Charles

were both present at the battle.

By early

July much of the countryside east of Ghent had been overrun by Philip’s

soldiers. Philip was joined by his nephew John of Cleves as Philip prepared to

invest Ghent itself. He had taken good care to retain the support of other

Flemish towns who supported their liege lord in diverse ways[iv].

|

| Philip receives the surrender of Ghent |

In June

Charles VII had instructed ambassadors to negotiate a settlement between the

two warring parties and by mid-July Philip was forced to sign a six week truce.

He then bribed the ambassadors to prepare a treaty that very much favoured

himself which was rejected by Ghent. Philip had his captains garrison the

surrounding towns as he laid off his armies for the winter.

Throughout

the winter and spring various offers and counter-offers were made between the

two warring parties. Philip’s final offer was dismissed in early June and on 18th

he and his army set out from Lille. His fleet was mobilised at Sluys,

blockading the sea route up to Ghent.

En route to

Ghent Philips’ army took the few outlying castles held by his enemies and on 23rd

July 1453 at the Battle of Gavere the men of Ghent broke ranks and

made for the local woods where they were annihilated. Philip refused to destroy

the town after this victory and the terms he imposed on the town were little

different from the terms refused the previous year.

Visiting the Holy Roman Emperor

|

| Feast of the Pheasant - Isabella (2L) and Philip (3L) |

On 17th

February 1454, at the Feast of the Pheasant at Lille, Philip swore to go on

crusade. His vow was hedged about with conditions that meant he was very

unlikely to actually leave for the Holy Land. He was followed by about a hundred of his courtiers eager to please

their duke. Even Hue de Lannoy, now seventy, took the vow.

Late the

following month Philip was summonsed by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III, as a Prince of the empire, to

attend the Imperial Diet. Frederick wanted to discuss the

projected crusade.

Philip left Lille on 24th

March 1454 with an escort of just thirty men. The fifty-four year old pushed

himself hard and arrived at Regensburg in the company of the Duke of Bavaria on 23rd April[v].

|

| Louis of Bavaria |

‘We met Duke Louis of

Bavaria…..coming towards my lord [Philip] accompanied by Cardinal Peter[vi]

of Augsberg and

a large company of chivalry. He received my lord the duke there and took him to

his town of Lauingen

that evening.’[vii]

Philip was

disappointed to find the emperor unavoidably detained with fighting on his

southern Hungarian border. He would have liked to have had the emperor invest

him with his imperial landholdings. Philip did manage get himself on good terms

with a number of the great and good of the Holy Roman Empire and laid the

foundations of future alliances. Philip hoped to have secured his northern

borders while he was on crusade.

Philip’s

return journey was via Landshut where he stayed for a few days as

the guest of the Duke of Bavaria; once again he was struck down by illness. He

was unwell for ten days, probably an intestinal complaint. Philip finally

returned home in early May, locating himself at Salins.

An Unexpected Visitor

|

| Louvain |

The ruling

in Rome in July 1456 that Joan of Arc had been tried illegitimately by the

English with the assistance of the Burgundians was a feather in Charles VII’s

cap. It confirmed his legitimacy as ruler of France. In October of that year

Philip found himself with an unwelcome visitor; the Dauphin Louis was a refugee

from his father’s court and paternal animosity[viii]. Louis arrived in Louvain accompanied by one hundred followers. He was informed that Philip would

meet him in Brussels on the 15th October.

Louis was

greeted by Isabella and Isabella of Bourbon who insisted that the Dauphin

precede them into the building. Louis was not a great one for formality but

Isabella, in view of the formality of the Burgundian court, protested;

‘Monsieur you must be making

fun of me. Otherwise you would not urge such an impropriety.’[ix]

|

| Genappe |

When Philip

arrived in Brussels Louis again had to be dissuaded by Isabella from breaking

with the formality of Burgundian court tradition[x] by riding out to meet

Philip. Philip housed Louis and his entourage, giving him a pension of 36,000

livres per annum[xi]

and allowing him the use of the castle at Genappe.

By the end

of October Philip and Louis sent a joint conciliatory embassy to Charles VII;

Louis claimed that he had come to Burgundy to join in Philip’s crusade. But the

French king had taken advantage of Louis’ departure from the Dauphiné to take the region’s fortresses. Philip’s deputation to Charles VII was

met with the response that Charles VII held Philip responsible for Louis’

behaviour. He informed his intimates that;

The Duke of Burgundy has

taken in a fox that will eat his chickens.’[xii]

A Familial Dispute

|

| Philip (CL) and Charles (CR) |

There had

long been disagreement between Philip and his son over the influence of the de

Croy family at court. The two senior de Croys were on the duke’s council and

were both founding members of the Order of the Golden Fleece. Both brothers

amassed amazing fortunes in Philip’s service that included bribes taken from

France.

Antoine de

Croy was one of two principal governors of the Netherlands, governor of

Luxembourg, Namur and Boulogne and Captain of St Omer. His son was ducal

chamberlain and his brother Jehan was succeeded as bailiff and captain-general

of Hainault by his son Philippe.

The two

brothers behaved as rulers in their own right, toadying to Philip who seemed

unable to understand that the de Croys supported Charles VII despite Philip’s

continuing advancement of the interests of the de Croy families. Descended from

a mere banneret, Philippe de Croy demanded the

daughter of the Count of St Pol as his son’s bride. St Pol refused and found

his lands confiscated by Philip.

In 1456

Antoine de Croy seized some lands that were due to be inherited by Charles. In January

1457 the dispute between Philip and Charles broke out into a series of violent

quarrels. Charles refused to give Philippe de Croy a post in his household, a

position he had reserved for Antoine Rolin, the Chancellor’s son. The quarrel

took place in the oratory of the ducal palace at Brussels and Isabella hastily

removed her son from the scene.

|

| Forest of Soignes |

Philip

decided to leave for Hal at night, on his own, arranging to meet the de Croy

brothers there. He got lost en route in the forest of Soignes and sought shelter in a charcoal burner’s cottage as search

parties scoured the countryside.

Not long

after this affair the duchess abandoned the court and her retirement was attributed

to;

‘The discord that had arisen

between her son and her husband. The Duke thought this had been caused by her,

therefore he would no longer speak to her.’[xiii]

She was not

alone in deserting the court, Nicolas Rolin followed suit shortly thereafter.

His departure was engineered by the de Croys.

Bibliography

The Fifteenth

Century – EF Jacob, Oxford University Press 1997

Margaret of

Anjou – Helen E Maurer, Boydell Press 2003

Louis XI –

Paul Murray Kendall, Sphere Books Ltd 1974

Isabel of

Burgundy – Aline S Taylor, Madison Books 2001

Philip the

Good – Richard Vaughan, Boydell Press 2014

The

Hapsburgs – Andrew Wheatcroft, The Folio Society

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

Which Philip had recently provisioned; its garrison was positioned to help cut

off Ghent’s river trade

[ii]

Philip the Good - Vaughan

[iii]

His lands and titles were passed to Anthony, Philip’s second favourite

illegitimate son

[iv]

Some towns and provinces provided fighting men; others sent boats or tents etc.

[v]

Philip had been ill on the journey and had stayed with the duke for several

days at Lauingen

[vi]

Bishop-Prince of Augsberg

[vii]

Philip the Good - Vaughan

[viii]

Louis had rebelled against his father in 1440 and incited the nobility to revolt. He was pardoned but

continued to intrigue against Charles VII. In addition Louis passionately hated

his father’s mistress Agnes

Sorèl who caused his mother much grief

[ix]

Louis XI - Kendall

[x]

The strict etiquette of the Burgundian court was inherited by Philip’s

descendants and was adopted in the Spanish court and spread from there to the

French court at Versailles

in the 17th century

[xi]

In 2015 the relative: historic standard of

living value of that income or

wealth is £26,680,000.00 labour earnings of

that income or wealth is £214,400,000.00 economic status value of that income or wealth is £868,100,000.00 economic power value of that income or wealth is £16,070,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[xii] Louis XI - Kendall

[xiii]

Philip the Good - Vaughan

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.