|

| Bruges Market Square |

Trouble in Bruges

Philip spent

Christmas 1436 in Bruges without serious incident, although his seven hundred

strong bodyguard were called out one night when news arrived that some of the

crafts guilds were assembling in the market place. The news was false, but

showed how on edge Philip was. The discontent in his lands had not died down.

In April one

of the Burgomasters of Bruges and his brother were murdered because;

‘He

worked with the prince to keep down the common people of Bruges.’[i]

|

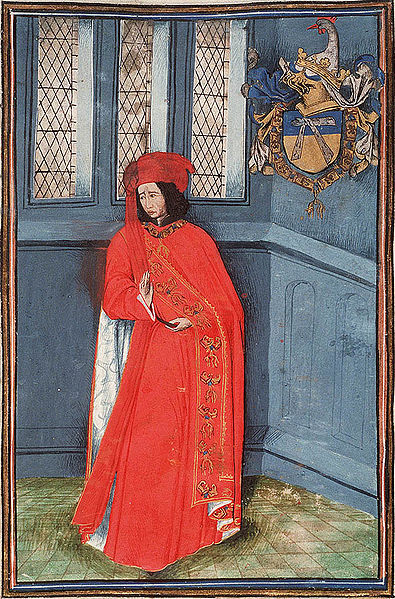

| Jehan de Villiers de L'isle Adam |

Many of

Bruges wealthy citizens fled and Ghent too saw riots in April 1437. Philip

decided to frighten his subjects into obedience by marching his army through Bruges.

The attempt to overawe failed and on 22nd May Philip escaped death

by a hairs-breath when his troops fired on the townspeople in the Fridaymarket.

‘The prince stationed

himself on the higher ground of the Fridaymarket….there he was with his nobles,

armed, holding a drawn sword in his hand, sitting up on his horse while his men

either shot at the common people of Bruges or laid about them with their swords

and wounded many.’[ii]

Philip’s

most trusted captain, Jehan de Villiers de L’isle Adam was not so fortunate and died on the

streets of Bruges. The people turned on Philip’s troops killing seventy-two of

them. Philip escaped the town and left for Lille. Twenty-two of Philip’s men

were captured and were executed by the citizens of Bruges.

The Aftermath

.JPG/800px-0_Sluis_-_Stenen_Kade_(1).JPG) |

| Sluys |

Philip was

now at war with his own people. He attempted to starve Bruges into submission. The

Zwin[iii] was staked meaning that no ships

could travel up to Bruges and the town’s mercantile privileges were given to Sluys. Bruges responded in July by besieging Sluys; Philip raised the siege

before the end of the month. Ghent was drawn into the maelstrom with its

attempts to mediate which almost resulted in a war between Bruges and Ghent.

Flanders was

riven by rebellion, warfare and civil chaos and it was not until February 1438

that agreement was reached at Arras. Bruges agreed to peace terms with her duke

that were humiliating in the extreme. The civic authorities were to meet Philip

outside the town, bare-headed and bare-foot and kneel in apology to him.

The gates

that had been barred against Philip were to be torn down and in its place a

chapel was to be erected to hear a perpetual mass for those killed in the

fighting. Bruges was also fined among many other penalties. Philip required

forty citizens to be nominated for execution before he could bring himself to

forgive Bruges. Ten of the citizens suffered the ultimate penalty and their

heads adorned the city gates.

Things were

no better as famine stalked the land elsewhere. Rotterdam rioted in 1439, the riots linked to a shortage of corn. Holland found

itself fighting the Hanseatic League and the Duke of Holstein in a mercantile war.

‘[We] have consented and

agreed on behalf of our gracious lord Burgundy, count of Holland, that the Duke

of Holstein’s subjects and those of the six Wendish

towns[iv]

may be damages, seized and injured in lives and goods wherever they can be

found.’[v]

The war

lasted nearly three years as the Hollanders attacked all Hanseatic shipping. The

war was inconclusive and netted no gains whatsoever, bar a few attacks on

neutral shipping.

Allies and Enemies

|

| Nuits St Georges |

Meanwhile

Philip’s southern lands were increasingly attacked by écorcheurs or flayers, so-called because they stripped their

victims of everything. Encouraged by Charles VII, the écorcheurs ensconced themselves in the heart of Philip’s duchy,

concentrating around Nuits St Georges and Beaune.

The governor

of Burgundy Jehan de Fribourg levied troops to defend the duchy. These troops

were as much a menace to the local population as the écorcheurs and the local population rose up in revolt in the winter

of 1437-8. Towns throughout the duchy refused aid to the troops which were

ostensibly meant to protect them. In September 1438 Charles VII ordered the écorcheurs out of southern Burgundian

lands; he was ignored and the écorcheurs stayed

until the mid-1440s[vi]

creating havoc throughout Philip’s southern domains.

In May 1438

Hue de Lannoy, in his role as Stadtholder of Holland, led a Burgundian embassy to England to discuss

mercantile matters. By August Flemish economic interests were also under

discussion. A conference in Gravelines in December 1438, headed by Isabella for Burgundy and her uncle,

Cardinal Henry Beaufort, for the English and a follow-up the

next year led to an Anglo-Burgundian trade treaty[vii] in September 1439[viii]. From now on Philip was

to remain neutral between the English and the French.

|

| James II of Scotland |

Philip was

careful to arrange treaties with his neighbours and this included Scotland. The Burgundians had been treating

with the Scots since 1426 when Philip sent his first embassy which resulted in

a commercial treaty signed the following year. In 1449 the daughter[ix] of the Duke of Guelders was sent as the bride of the young

King James II. James wanted grooms for his sisters

and, lacking in legitimate daughters Philip made use of the daughters of his

nobility or of nobles indebted to him.

Relations

between France and Burgundy were not as friendly and Philip frequently had

cause to complain to Charles VII about anti-Burgundian actions by the French.

Even after Philip requested and obtained a French princess as bride for his son

Charles, matters were still often fraught. The Paris Parlement had directions from the king to ignore Burgundian cases

brought before them. There was little or no attempt to deal with the écorcheurs who were referred to by the

Burgundians as ‘les gens du roi’[x].

Early in 1441 Isabella

was sent to Paris on Philip’s behalf to present a series of complaints to

Charles, none of which were accepted. She returned back to Burgundy to report

on her failure; from now on Philip and his councillors were seldom without

worries about possible invasion from France.

Dealings With France

.jpg/397px-SOAOTO_-_Jean_de_Bourgogne_(1415-1491).jpg) |

| Jehan de Burgoyne |

There was a noisy group of courtiers at the French court who

proselytised for war with Burgundy; they included Philip’s brother-in-law

Arthur de Richemont. The causes of complaint ranged from fishermen’s attacks on

Flemish commerce to claims on the county of Étampes which Philip had granted to his cousin Jehan de Burgoyne[xi].

From 1442 onwards the Dauphin Louis led troops

into his cousin’s lands. In 1442 he attacked the countryside around Dieppe, in 1443 it was the area around Montbéliard that suffered his depredations. His father besieged Metz while Louis attacked the Swiss with the assistance of the écorcheurs. The French had been freed

up to attack Burgundy by the Anglo-French truce signed in Tours on 28th

May 1444.

In March

1445 Isabella met with Charles VII at Rheims and produced a list of thirty-two

complaints. In May a further set of complaints were presented. Charles and his

son meanwhile were attacking Burgundy and the Marshal of Burgundy Thibaud de

Neuchâtel reported to Isabella that;

|

| Rene of Anjou |

‘The king and my lord the

dauphin had secretly ordered these troops to live off Burgundian territory

until the conference at Rheims…..and to act in such a way as to ensure that

complaints were made about them.’[xii]

The ravages

continued after the end of the conference at Châlons in July 1445. A French

captain attacked Mâcon and Charolais. Philip was forced onto the defensive and

found himself making concessions to the French crown, concessions supported by

his French leaning councillors, in particular the de Croys who like many others

were on the French payroll.

The major

concession Philip made was the release of René of Anjou from all his

obligations towards Philip, including the ransom of 400,000 gold crowns[xiii] which he could not

afford to pay. The treaty was signed on 6th July but Philip got

nothing in return for his virtual surrender to Charles VII bar Charles agreeing

to evacuate his troops from Montbéliard.

Bibliography

The Hundred

Years War – Alfred Burne, Folio Society 2005

The Reign of

Henry VI – RA Griffiths, Sutton Publishing Ltd 1998

Europe:

Hierarchy and Revolt 1320-1450 – George Holmes, Fontana 1984

The

Fifteenth Century – EF Jacob, Oxford University Press 1997

Louis XI –

Paul Murray Kendall, Sphere Books Ltd 1974

Isabel of

Burgundy – Aline S Taylor, Madison Books 2001

Philip the

Good – Richard Vaughan, Boydell Press 2014

Charles the

Bold – Richard Vaughan, Boydell Press 2002

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

Philip the Good - Vaughan

[ii]

Ibid

[iii]

A tidal inlet connecting Bruges to the sea

[v]

Philip the Good - Vaughan

[vi]

When the Dauphin led them against the Swiss

[vii]

The Anglo-Dutch treaty took until 1445 to settle outstanding issues and the

Dutch had to pay reparations.

[ix]

Philip’s great niece

[x]

The king’s people

[xii]

Philip the Good - Vaughan

[xiii]

In 2015 the relative: historic standard of

living value of that income or

wealth is £321,200,000.00 labour earnings of

that income or wealth is £2,360,000,000.00 economic status value of that income or wealth is £11,310,000,000.00 economic power value of that income or wealth is £210,000,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

a person less deserving of the epithet 'the good' it would be hard to find

ReplyDelete