|

| Bonne and John |

Born in Pontoise, on 17th January 1342, Philip the Bold was the youngest son of the Dauphin of France John II, and his wife Bonne of Bohemia. Philip was named after his grandfather Philip VI, King of France. Bonne died of the plague in 1349 when Philip was seven. Bonne also had six daughters,

two of whom predeceased her, Margaret died in 1352. Joan[i] was born the year after Philip, Marie[ii] born in 1344 and Isabelle[iii] in 1348.

In July 1346,

when Philip was four years old, Edward III of England launched a major invasion

of France[iv] and on 26th

August the English annihilated the French, who were caught unawares, at the Battle of Crécy. The chronicler Matteo Villani wrote;

‘The English guns cast iron

balls by means of fire. They made a noise like thunder and caused much loss in

men and horses….the whole plain was covered by men struck down by the arrows

and cannonballs.’[v]

|

| Battle of Crecy |

Over 1,500

French lords and captains died along with 10,000 other ranks. King Philip fled

to Amiens and Edward cast his eyes on Calais to regroup and re-victualise his army.

He proceeded to besiege the town which fell to the English

in 1347. Edward III allied himself with Charles the Bad, the king of Navarre who had been offered the hand of Joan of France, albeit

without any dowry. Charles had been turned down as Constable of France in favour of Don Carlos de la Cerda, and now Charles was prepared to make

John pay for what he deemed insults.

Philips’

grandfather King Philip did not die until August 1350 when Philip was eight.

John lacked his father’s capabilities, lacking any subtlety; he was a bluff

cheerful man.

Poitiers

|

| the Black Prince |

In September

1355 the Black Prince conducted a grande chevauchée from Bordeaux to Narbonne and back. In

the spring of 1356 John gathered together a mighty army to put in the field

against the invaders. He and his military advisers lacked the strategic

brilliance of the Black Prince and Sir John Chandos.

On 19th

September 1356 the two sides met again at the Battle of Poitiers; once again the English routed the French army. In

the midst of battle the Dauphin Charles fled the fighting while his father

laid about himself with his battle-axe cheered on by the fourteen year old

Philip, who cried out warnings to his father;

‘Beware father to the right,

beware to the left.’[vi]

Philip’s

exemplary behaviour during the frenzy of battle meant that thereafter he was

endowed with the soubriquet of Philip the Bold.

.jpg/687px-Battle-poitiers(1356).jpg) |

| The Battle of Poitiers |

John II was

taken prisoner during the battle despite having dressed nineteen members of his

entourage in identical raiment to himself. In the aftermath of John’s capture

English lords jostled to claim him as prisoner when he told them

‘I am so great a lord that I

can make all of you rich.’[vii]

Chivalry was

set aside when it became a question of making money from ransoms and booty; aside

from John’s ransom the English made over £300,000[viii] in money from this one

battle alone, more than covering Edward’s outlay for the war that year.

Captivity

|

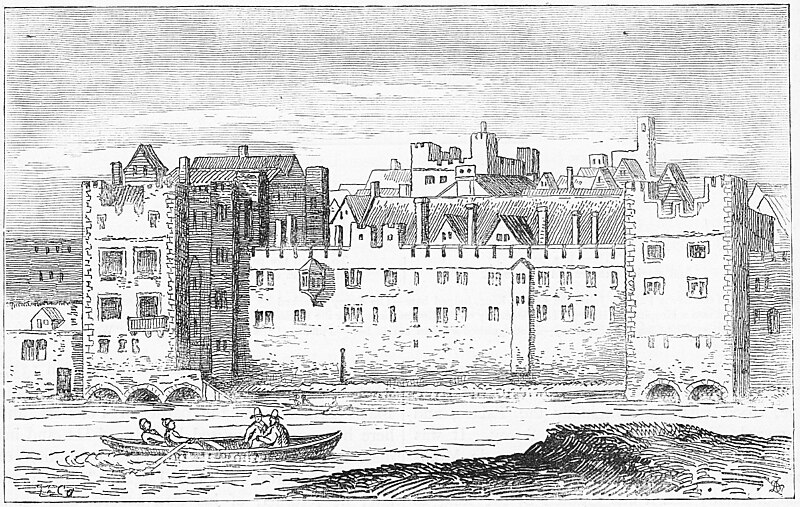

| The Savoy Palace |

Philip and

his father were taken to England while Edward awaited the payment of John’s

ransom. He was paraded through the city of London on a;

‘Whyte courser, well

apparelled, and the prince on a lyttell black hobbey by hym.’[ix]

Father and

son were to spend the first months of their captivity at the Palace of the Savoy, recently built by Edward’s third son John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster at a cost of 52,000 marks[x]. They were frequently

visited by Edward and his queen Philippa of Hainault[xi]. Philip played chess with the Black

Prince and was taught the art of falconry by the French royal chaplain, Gace de

la Buigne[xii],

who had gone into captivity to be with his master. John and Philip were guarded

to ensure they did not escape and to prevent any attempt at a rescue.

|

| Windsor Castle |

The first

winter of their imprisonment John and Philip were treated to extravagant

festivities by the English court, including a tournament held by torchlight. In

the summer John and Philip were moved to Windsor Castle where they were able to enjoy hunting and hawking.

A number of

the imprisoned French nobles were placed on parole to enable them to visit

their monarch. Languedoc

sent a delegation of nobles and bourgeois and a gift of 10,000 florins[xiii], along with the

assurance that their lives, goods and fortunes were dedicated to the king’s

delivery from this shameful imprisonment. Laon and Amiens were among towns that

sent money to succour their monarch.

John spent

the monies on elaborate clothing for himself, his son and his jester who

received several hats trimmed with ermine, gold and pearls. He also purchased

horses, dogs, falcons, a chess set, an organ, a harp and a clock. In addition

the money from his loyal subjects went towards an astrologer and a ‘king of

minstrels’ along with an orchestra.

The

negotiations for John’s release were hampered by Edward’s demands; he wanted

outright cession of Guyenne, Calais and all former Plantagenet holdings in

France. In return for that and three million eçus[xiv] Edward would give up his

claim on the French throne.

Turmoil in Paris

|

| Paris |

When the

Dauphin returned to Paris after Poitiers he was

‘Received with honour by the

people, grief-stricken by the capture of his father the king.’[xv]

They

believed that the Dauphin would bring about his father’s release and save the

country. John’s capture at Poitiers resulted in a power struggle between the

Dauphin, Regent in his father’s absence, and Charles of Navarre who claimed the

throne of France in his own right. Charles of Navarre was allied with Estienne Marcel[xvi], leader of the third Estate[xvii] in Paris.

Instead the

Dauphin found himself beleaguered by Marcel’s plans to contain the monarchy.

The delegates of the Estates General of Paris met in October and the

Dauphin, embarrassed by his failure at Poitiers had to ask for aid to help

deliver the king from the English and to defend the kingdom.

|

| Robert le Coq (front L) |

The crown’s

opponents were not united which gave the Dauphin some leeway when Marcel tried

to raise Paris against his regency. In March 1357, with a general strike

declared the Dauphin was forced to come to terms with Marcel and his

opportunistic cronies who included Robert le Coq, Bishop of Laon who longed to be Chancellor of

France and bore a grudge against the Valois rulers of France for failing to

give him the post. Prince Charles was browbeaten into signing off the demands

of his opponents by the threat of mob rule in Paris.

Bibliography

Edward III –

Bryan Bevan, the Rubicon Press 1992

The Hundred

Years War – Alfred Burne, Folio Society 2005

Chronicles –

Froissart, Penguin Books 1968

Europe:

Hierarchy and Revolt 1320-1450 – George Holmes, Fontana 1984

The Fourteenth

Century – May McKisack, Oxford University Press 1997

The Perfect

King – Ian Mortimer, Vintage Books 2008

Hawkwood –

Frances Stonor Saunders, Faber and Faber 2004

A Distant Mirror

– Barbara Tuchman, Papermac 1989

Philip the

Bold – Richard Vaughan, Boydell Press 2011

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

Joan was to marry the king of Navarre

[iv]

He had put forward his claim to the French throne in 1337 as the only male

grandchild of Philip

IV of France. The French chose the grandson of Philip III

[v]

Edward III - Bevan

[vi]

Ibid

[vii]

Hawkwood - Saunders

[viii]

In 2016 the relative: historic standard of

living value of that income or

wealth is £197,200,000.00, labour earnings of

that income or wealth is £2,412,000,000.00, economic status value of that income or wealth is £5,411,000,000.00, economic power value of that income or wealth is £107,800,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[ix]

Edward III – Bevan

[x]

In 2016 the relative: historic opportunity

cost of that project is

£31,810,000.00, labour cost of that

project is £418,000,000.00, economic cost of

that project is £18,680,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[xi]

Who had acted has her husband’s regent the previous year

[xii]

Author of Le Roman de Deduis written

circa 1377, a book of the hunt

[xiii]

In 2016 the relative: historic standard of

living value of that income or

wealth is £6,573,000.00, labour earnings of

that income or wealth is £80,390,000.00, economic status value of that income or wealth is £180,400,000.00, economic power value of that income or wealth is £3,592,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[xiv]

In 2016 the relative; historic standard of

living value of that income or

wealth is £1,972,000,000.00, labour earnings of

that income or wealth is £24,120,000,000.00, economic status value of that income or wealth is £54,110,000,000.00, economic power value of that income or wealth is £1,078,000,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[xv]

A Distant Mirror - Tuchman

[xvi]

The head of a reform movement that

tried to institute a controlled French monarchy, confronting the royal power of

the Dauphin

[xvii]

The other two estates were the noblesse

de epée (nobility) and the noblesse

de robe (the clergy)

[xviii]

John had arrested Charles in 1356 for trying to foment discord between John and

his heir