|

| Caterina Sforza |

On 26th

February Caterina arrived in Rome in Cesare’s entourage during carnival. Cesare

was met at the gates of the city by all the cardinal’s households and the papal guard. According to some accounts Caterina was allegedly dressed as the Queen of Palmyra, in black with a restraining gold chain round her neck. Cesare

was also soberly garbed;

‘Don Cesare had around him a

hundred grooms, each one dressed in a cloak of black velvet with black leather

boots and carrying a new halberd in his hand. Don Cesare himself was dressed in

a coat of black velvet reaching to his knees, with a collar of simple and

severe design.’[i]

Alexander VI

greeted Caterina cordially upon her forced return to the eternal city. She was

lodged in the Villa Belvedere[ii]

within the Vatican grounds; the pope carefully avoided treating her like an

exhibit in Cesare’s triumph, for fear of an adverse reaction on the part of his

ally Louis XII. On the 27th February the Mantuan ambassador met with

Caterina and described her as ‘still

furious and strong-willed’.

Caterina was

allowed her servants and ladies-in-waiting along with her confessor. Upon

Caterina refusing to relinquish formal control of Forli and Imola back to the

church twenty soldiers were sent to guard her day and night. In late May, with

the help of a Milanese friar, one Lauro Bossi, Caterina attempted to escape.

She was betrayed by one of Bossi’s go-betweens and was captured by the guard.

For her

pains Caterina found herself imprisoned in a small dungeon in the Castel Sant’

Angelo. She was allowed two servants to attend to her. Caterina’s plight

was not aided by the fall of Ludovico Sforza who was taken off to imprisonment

in France. Hitherto, Caterina had been looked after for fear that Ludovico

would march on Rome in defence

of his niece.

Freedom

Ottaviano

was reluctant to aid his mother, with whom he had a conflicted relationship.

While Caterina got on with her younger children, she had a troubled

relationship with both of Girolamo’s sons; Ottaviano, who had inherited much of

his father’s character and had not cared for Caterina’s refusal to turn over

control of his lands to him, and Cesare[iii].

Ottaviano offered to hand over the lordship of both Imola

and Forli in return for his mother’s release and a cardinal’s hat for his

brother Cesare. Ottaviano and Cesare wrote to Caterina saying that they were

now washing their hands of her.

|

| Fortezza Vecchia, Livorno |

‘If His Holiness does not grant our latest petition then don’t expect any

more from us. We have impoverished ourselves.’[iv]

Alexander refused the offer.

In June 1501 Alexander received a demand from Yves d’Allègre[v], on

behalf of Louis XII, that Caterina be freed. He agreed in return for her formal

renunciation of Imola and Forli. By this time a shadow of her former self, Caterina

signed the required documents on 30th June and left the Castel

Sant’Angelo. She stayed as a guest of Cardinal Raffaele Riario for a few days.

2,000 ducats[vi]

were forthcoming from Florence to cover the cost of her return there. Caterina

travelled by night in an attempt to avoid any mischance on the part of Cesare

or his family. She left from Ostia and

travelled by sea to Livorno.

Legal Troubles

Throughout her confinement Caterina’s main worry was

Ludovico who had fallen into the hands of his paternal uncle, who had made

himself Ludovico’s guardian. Lorenzo di Popolani de’ Medici had his eye on his

nephew’s inheritance and he applied to have Caterina declared unfit. With

judicial use of his fortune Lorenzo was able to persuade the Florentine courts to award him custody

of the four year old Ludovico.

As soon as she arrived in Florence Caterina received news

from a relative who reported that;

‘He [Ludovico] has grown and is a beautiful gallant boy.’[vii]

|

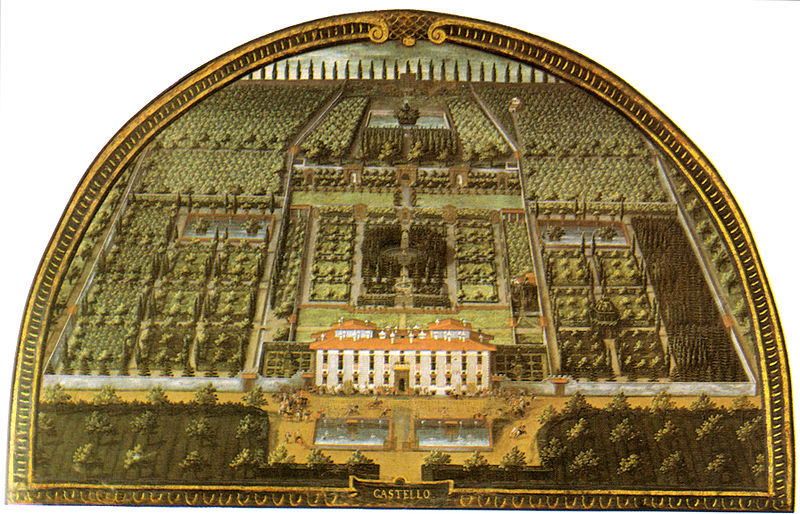

| Villa di Castello |

Lorenzo il Popolano left Florence with Ludovico almost

immediately and Caterina wrote to Mantua and to her sister Bianca Maria the Holy

Roman Empress. Caterina was looking for support in high places to get her son

back. She was not allowed to see Ludovico during the battle for custody.

Caterina

moved to the Medici Villa di Castello[viii] to get away from her

brother-in-law’s harrying. Penniless herself, Caterina was being pressed by

Ottaviano and Cesare for financial assistance.

|

| Julius II |

In June 1502

Lorenzo tried to force her to leave the sanctuary she had found, claiming the

Villa di Castello as his own personal property and used the caretaker to make

her life miserable. She had no sheets or tablecloths and had to beg her

children for six forks. When her stepson Scipione Riario arrived to visit

Caterina was worried about the additional cost of providing for him and his

companions.

On the 20th

May Lorenzo died and Caterina was able to take custody of Ludovico once again.

The dispute over the control of Caterina’s dower monies was not settled until 5th

June 1505. Caterina returned to the Villa di Castello with Ludovico, whose name

she now changed to Giovanni, and Carlo, her son by Giacomo Feo. She taught

Giovanni how to ride and hunt.

On 28th

July 1503 Caterina married her daughter Bianca off to Troilo Rossi, the first Marchese di San Secondo.

Less than a month later Pope Alexander died and Cesare fell ill[ix].

After a short reign by Pius III,

Guiliano della Rovere ascended the papal throne as Julius II.

Alchemical Experiments

|

| Isabella d'Este |

Like many other

fashionable ladies, including Lucrezia Borgia and Isabella d’Este, Caterina made her own perfumes and love potions and diverse

ointments to encourage ‘masculine

virility’ as well as salves and cosmetics, sleeping potions and

painkillers. The ingredients Caterina used were often esoteric and included

such items as newts and the juice of red ants. Her expenditure on ingredients

outran her income[x].

Her experiments were posthumously published as Gli Esperimenti.

Caterina

still held hopes that Julius II would grant Forli to Ottaviano and in October

1503 advised him to press the pope on the matter, writing;

‘The iron is hot and it is

time to strike it….Guard yourself from those you trust and those who offer you

advice. Know the foul tempers that are all around you; if you allow yourself to

be led by others, you will wind up with your cap over your eyes, so wake up!’[xi]

|

| Viterbo Cathedral |

Alas for

Ottaviano Caterina’s hopes came to nothing; Ottaviano and Cesare did not make

many friends, having inherited their father’s arrogance. In 1507 Ottaviano

became bishop of Viterbo and Volterra, the dioceses having been ceded to

him by his uncle Raffaello Riario. He still hung on his mother’s purse strings

and wrote demands for money for clothing, so that his fellow prelates did not

outshine him.

For herself

Caterina spent her days in correspondence and took lovers to her bed, although

neither they nor she were as young as they were in her heyday. In 1508 Bianca

brought her son Pietro Maria and her new daughter to visit their grandmother.

Pietro Maria was left in Caterina’s care so that she could teach him to ride

and hunt, as she had done for Giovanni who had little interest in schooling.

Caterina

died on 28th May 1509; she suffered pleurisy which made breathing

difficult, brought on by the quartan fever she had suffered from for most of

her adult life. She made her will that day, leaving a bequest for the upkeep of

the cathedral in Florence and paying for 1,000 masses for her soul. She left

provision for her grandchildren and left Carlo Feo 2,000 gold ducats[xii].

Caterina’s

favourite child Giovanni was to follow in his maternal grandfather’s footsteps

to become a condottiere; known as Giovanni della Bande Nere. He married Maria Salviati, the

daughter of Jacopo Salviati and Lucrezia di Lorenzo de' Medici. His

son was Cosimo I de'

Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany.

Bibliography

At the Court

of the Borgia – Johann Burchard, the Folio Society 1990

Lucrezia Borgia – Rachel Erlanger, Michael Joseph 1979

The Deadly

Sisterhood – Leonie Frieda, Harper Collins 2013

The Borgias

– Mary Hollingsworth, Quercus Editions Ltd 2014

Tigress of

Forli – Elizabeth Lev, Head of Zeus Ltd, 2012

The Borgias

– GJ Meyer, Bantam Books 2013

Absolute

Monarchs – John Julius Norwich, Random House 2011

Niccolo’s

Smile – Maurizio Viroli, IB Tauris & Co Ltd 2001

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

At the Court of the Borgia - Burchard

[iv]

Tigress of Forli - Lev

[v]

Commander of the French troops in Italy

[vi] In 2016 the

relative: historic standard of living value of that income or wealth is £1,322,000.00, labour earnings of that income or wealth is £13,040,000.00, economic status value of that income or wealth is £34,600,000.00, economic power value of that income or wealth is £808,200,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[vii]

The Deadly Sisterhood - Frieda

[viii]

In the hills above Florence

[ix]

Rumour had it that the two men ate from a poisoned dish intended for another

victim

[x]

She was in debt to the tune of 587 florins at the time of her death. In 2016 the relative: historic standard of

living

value of that income or wealth is £483,000.00, labour earnings of that income or wealth is

£3,817,000.00, economic status value of that income or wealth is £9,866,000.00, economic power value of that income or

wealth is £227,700,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[xi]

Tigress of Forli - Lev

[xii]

In 2016 the relative: historic standard of

living

value of that income or wealth is £1,646,000.00, labour earnings of that income or wealth is

£13,010,000.00, economic status value of that income or wealth is £33,610,000.00, economic power value of that income or

wealth is £775,900,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

2,000 ducats, a sum mentioned twice, would have been about the equivalent of 400 English sovereigns, about the yearly income of a baron or a wealthy wool merchant, enough to pay the salary of 20 schoolmasters or one hundred labourers for a year. A ducat was approximately 4/- to 4/8d and I've erred there on its lowest purchasing power. It was considered approximately equivalent to the Florentine Florin, the French Écu and the English Crown. The Crown was generally reckoned to be 5/-

ReplyDelete