Richard II murdered circa 14th February 1400

Richard was

the son of the Black Prince, a warrior of great renown & grandson of Edward

III. He succeeded his grandfather at the age of 10 in 1377. A regency of the

king’s uncles was avoided. Many of the nobility feared the ambitions of John of

Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, who had been effectively running the country during

the final illnesses of his elder brother & father. Gaunt was still very

influential during Richard’s minority.

Heavy poll

taxes, the proceeds of which were used to prosecute the war in France, were one

of the root causes of the Peasant’s Revolt in 1381. Following the loss of up to

60% of the population in the Black Death in the middle of the 14th

century labourers were in short supply. But the Statute of Labourers of 1351

forbade the movement of peasants & the seeking of better wages. The nobles

surrounding the king, particularly his uncle John of Gaunt, were immensely

unpopular.

The revolt

was triggered by poll tax collectors in Essex and quickly spread throughout the

region. With ploughshare & scythe the farm workers & labourers marched

on London, where they were eventually met by Richard (by now considered old

enough to rule at the age of 14). Richard agreed to parley with their leaders.

When the motley crew returned home, rejoicing at their triumphant meeting with

the king, the ringleaders were cut down; Richard having reneged on his promises

to his people.

Richard’s

friend Michael de la Pole was from a merchant family & when Richard made

him chancellor & later the Earl of Suffolk. De la Pole was viewed as an

upstart by the nobility. Richard’s friend Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford, was

also viewed with hostility, as the de Vere family was not of the top rank. De

Vere’s elevation to the newly created Duchy of Ireland merely fanned the

flames. The chronicler Thomas Walsingham claimed that relationship de Vere had

with the king was of a homosexual nature.

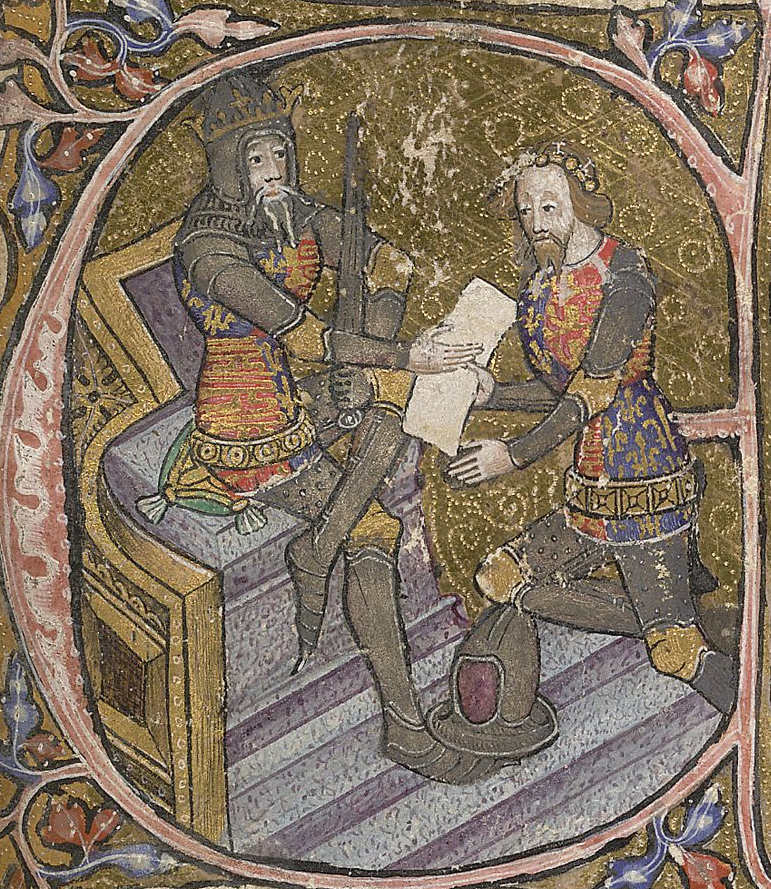

|

| The Duke of Lancaster at a banquet |

Richard’s

relationship with his uncle of Gaunt was further corroded by their polar

attitudes to the ongoing war with France. Richard preferred to negotiate with

the French, while the Duke of Lancaster wanted to protect the French lands

conquered by his father. In 1386 Gaunt

left England, with an army, to further his pretentions to the throne of

Castille. The proposed military actions in France required the Chancellor to

increase taxation to pay for the campaigns. Parliament refused to allow the

taxation unless de la Pole was removed from the Chancellorship. It wasn’t until

he was threatened with deposition that Richard allowed the removal of de la

Pole.

|

| The earl of Oxford escapes from Radcot Bridge |

Richard built

up a power base in Chester. But on his return to London, from a tour of his country

to raise support, Richard was met by the Duke of Gloucester, and the earls of

Arundel & Warwick. The three wished to raise pleas of treason against

Robert de Vere, de la Pole and other supporters of the king. Richard

procrastinated, as he was expecting de Vere with military reinforcements from

Cheshire. John of Gaunt’s eldest son, Henry Bolingbroke, earl of Derby, and the

earl of Nottingham met with the three lords and jointly intercepted de Vere, routing

his forces at Radcot Bridge. The Lords Appellant (as they became known) now

forced Richard to comply with their demands. De la Pole & de Vere fled to

the continent, but the king’s lesser supporters were executed, including Knight’s

of the King’s chamber.

|

| Richard & Isabella on their wedding day |

The Lords

Appellant were opposed to Richard’s strategy of negotiating with the French and

unsuccessfully attempted to set up an anti-French coalition. The return of the

Duke of Lancaster, from Castille, had a calming effect on English politics and

on 3rd May 1389 Richard took full control of his kingdom. He now

began negotiating a permanent peace with France. The price of peace with France

was for the King of England to do homage to the King of France for his French

possessions in Aquitaine, which was totally unacceptable to the English.

Eventually in 1396 a twenty-eight year truce was agreed, as well as the

marriage between Richard & the six year old Princess Isabella.

In the

autumn of 1394 Richard led an expedition to Ireland, where the English

lordships were under threat. Richard’s campaign was successful & he

returned to England in May 1395.

In July 1397

Richard had the Lords Appellant arrested. Richard had always been a great believer

in the Royal Prerogative and strongly felt that the Lords Appellant had acted

against his royal person when forcing the execution of Richard’s supporters. Arundel

was tried & executed in September. Then came the news that Gloucester had

died in prison. Warwick & Arundel’s brother, the Archbishop of Canterbury,

were exiled. John of Gaunt facilitated Richard’s revenge, but the king was assisted

by his half-brother John Holland & his nephew Thomas, now the Dukes of

Exeter & Surrey. The king also rewarded a number of his other remaining

supporters.

In December

1397 Henry Bolingbroke, now Duke of Hereford, fell out with Thomas de Mowbray,

now Duke of Norfolk. Before the matter could be decided by a trial of arms

Richard exiled both men, Mowbray for life & Bolingbroke for ten years.

However when

John of Gaunt died in February, Richard extended Bolingbroke’s exile to life.

Bolingbroke was at the French court, where in June 1399 Louis Duke of Orleans

took control of the court of the insane Charles VI of France. Louis was not

interested in the peace policy previously followed by both courts & allowed

Henry to return to England, where he claimed he was merely attempting to gain

his inheritance as Duke of Lancaster.

.jpg/180px-King_Henry_IV_from_NPG_(2).jpg) At the end

of June Henry arrived in Yorkshire & soon had men flocking to his banner. Richard

meanwhile was with his army in Ireland; from where he returned, landing in

Wales, on the 24th July. The Duke of York, as Keeper of the Realm,

in Richard’s absence, had already sided with Bolingbroke. By the 19th

August Richard had surrendered to Henry at Flint castle, promising to abdicate

if his life was spared. Richard was then taken to the Tower of London and on 30th

September Parliament accepted his resignation. Henry was crowned the fourth of

that name on 13th October 1399.

At the end

of June Henry arrived in Yorkshire & soon had men flocking to his banner. Richard

meanwhile was with his army in Ireland; from where he returned, landing in

Wales, on the 24th July. The Duke of York, as Keeper of the Realm,

in Richard’s absence, had already sided with Bolingbroke. By the 19th

August Richard had surrendered to Henry at Flint castle, promising to abdicate

if his life was spared. Richard was then taken to the Tower of London and on 30th

September Parliament accepted his resignation. Henry was crowned the fourth of

that name on 13th October 1399.

Shortly

before the end of the year, around the time of an uprising planned by Richard’s

supporters, Richard was moved to Pontefract Castle. Richard was under the care

of Sir Thomas Swynford, the son of the new king’s stepmother. In less than two months

Richard was dead.

It is

believed that Richard died of starvation; Henry IV and his council claimed that

Richard refused food for four days and was thereafter unable to eat & so

died. However the minutes for a council meeting on 8th February were

doctored after the event. The original document showed that the following

payments were authorised from the exchequer:

·

Payment to William Loveney, clerk of the Great

Wardrobe, sent to Pontefract castle on secret business by order of the king –

paid 66 shillings & 8d – in 2010 worth: £20,200.00 using average earnings

·

Payment to a valet of Sir Thomas Swynford to

certify to the council on certain matters, with concern to the king’s advantage

- 26 shillings & 8d – in 2010 worth:

£8,100.00 using average earnings[i].

These payments would seem excessive for

merely observing the king’s death & reporting it to king & council.

They would appear to confirm suggestions that Richard was murdered; possibly by

the withholding of food as suggested by the chronicler Adam of Usk, who also

claims that Sir Thomas Swynford taunted Richard ‘with starving fare’.

Bibliography

Edward III – WM Ormrod, Tempus

Publishing 2005

Richard II & the Revolution of

1399 – Michael Bennet, Sutton Publishing 1999

The Usurper King – Marie Louise

Bruce, The Rubicon Press 1998

www.en.wikipedia.org

[i]

The Usurper King – Marie Louise

Bruce, The Rubicon Press 1998

Price information from www.measuringworth.com