|

| Seal of Simon de Montfort |

The loss of

Carcassonne sent a shock wave throughout Occitane. The Cathar priests went

underground; the perfecti took off

their black robes, disguising themselves as burghers or artisans. The local

seigneurs professed the Catholic faith or took off into the mountains.

The

besiegers at Béziers had failed to distinguish between Catholic and Cathar in

their rapacity and now de Montfort decided to treat the whole region as

heretical. Between them de Montfort and the circa thirty knights of his

personal escort[i]

left with him could call upon the services of around 300 men, and the few

mercenaries that de Montfort could afford.

The region

was up in arms; in the south Raymond-Roger, Count of Foix[ii], had his forces intact

and in the west the Count of Toulouse was a most unreliable ally. And the

region around Limoux and Albi held numerous small strongholds held by the enemy.

Having been elected Viscount of

Béziers de Montfort was finding it difficult to give homage to his new liege

lord, the King of Aragon.

The

inhabitants of the region had reason to be wary of the religious zeal of the Captain-General of the army of the Church. In

1210, after the capture of Bram, which resisted for a mere three days, the

garrison of over 100 men was seized and de Montfort had their eyes gouged out

and noses and upper lips cut off. One man was left with a single eye and de

Montfort deputed him to lead his comrades to the scene of the next planned

action.

The cruelty

was not limited to just the Crusaders; there were instances of;

‘Knights being flayed alive,

chopped into pieces or otherwise mutilated.’[iii]

On both

sides; the influence of religion legitimised a descent into inhumanity; de

Montfort was content to allow rapine, fire slaughter and razing of lands that

he now considered his own. His actions went a long way to destroying what had

hithertofore been a vibrant economy. Simon de Montfort, during his reign of

terror, presided personally over three mass executions of perfecti.

The death of

Raymond-Roger of Béziers induced a revolt among his former vassals and isolated

garrisons were attacked. Forty chateaux were lost in a few months; including

the Chateau of Priexan, taken by the Count of Foix.

De Montfort

was able to alienate with ease those who had sworn oaths to him as their new

overlord. He treated all the Provençal seigneurs as his inferiors including

those who supported him. He distributed lands among his men; that were not his

to give. De Montfort also attempted to enforce French laws and customs on the

south, which had always been separate and different from the northern kingdom

of the Franks.

Regrouping – the de Montfort’s Rally

Minerve

In March

1210 de Montfort’s wife arrived, bring with her 100 much needed troops. De

Montfort retook the chateaux of Priexan and now marched on Minerve, supported

by the citizens of Narbonne. Minerve surrendered after being starved out and

cut off from their water supply. De Montfort was criticised for his leniency by

the Papal Legates. The legates were aware that a large number of perfecti had taken refuge in the city

and presumably wished to make examples of them.

The

negotiations were halted by the legates’ chicanery and the city surrendered

unconditionally. Everyone was expected to recant and repent or die. The

church’s fervent supporters were horrified that the perfecti might escape justice; they were pleased to be proved

wrong.

‘He had them brought forth

from the château; and a great fire having been got ready, more than a hundred

and forty of these heretical perfecti

were flung thereon at the one time.’[iv]

De Montfort

was now in a much stronger position which was boosted by the success of the

three month siege of the chateau at Termes.

Chateau de Termes

The church

was concerned that large numbers of the heretics were to be found in the lands

of one of the Crusaders, the Count of Toulouse. In September 1209 the Papal Legates

presented an indictment against him to the Pope. They claimed that he had not

made good his indemnifying of plundered abbeys and destruction of

fortifications.

By January

1210 Raymond VI had received an audience with the Pope. He claimed;

‘The Legates, who have

treated him exceedingly ill though he had already fulfilled the majority of his

obligations which our Notary….had imposed upon him.’[v]

The count

was treated leniently to ensure that he remained in the church’s camp. Raymond

VI was only to be attacked under Canon law and Arnald-Amalric was determined to

leave this enemy no loophole, and was prepared to use trickery to gain his own

way. In his turn Raymond VI wanted to come to an agreement with de Montfort and

two met in January 1211.

In an

attempt to clear his name, of the heinous

crimes he was accused of by Arnald-Amalric, Raymond VI attended a council at

Arles and was given a list of offensive conditions, not commensurate with one

of the count’s high estate and supporter hereto of the crusade. He was ordered

to;

·

Cease

protecting Jews and heretics and to surrender them within the year

·

Rid

himself of all mercenaries

·

Wear

brown homespun

·

Raze

all properties belonging to him and his nobles to the ground

·

They

were to live like villeins in the countryside; town life was forbidden to them

·

If

attacked by Crusaders they were to proffer no resistance.

These conditions were a considered insult and meant to be

discarded by Raymond. Arnald-Amalric was determined to force Raymond VI to

break with the Crusade, which is what happened. Raymond was much loath to do

so; it went against his pragmatic nature.

Having

declared war by leaving the Legates without an answer Raymond VI was

excommunicated and 6th February 1211 they decreed his domains forfeit

to the first person to take them.

Meanwhile de

Montfort was taking control of what remained of the lands belonging to the

former Viscount of Béziers. He seemed to think that there was no difference in

the fealty of his own vassals and those compelled by force majeur to swear

loyalty to him. Those Occitan knights who were foreworn of their forced oaths

were treated with a deliberate and terrible cruelty by de Montfort. In May 1211

the town of Lavaur saw the largest of the mass killings when four hundred people

were burned to death.

The Siege of Toulouse

In June 1211

de Montfort moved into the lands of the Count of Toulouse, who even now was

attempted peaceable overtures to the Papal Legates, who were pressurising the

Pope to ignore any representation on Raymond’s part.

‘If the Count were to obtain

the restitution of his Chateaux at Your

hands……everything we have done to procure peace in Languedoc would be

annulled.’[vi]

At the same

time there was another auto-da-fé in Cassès.

Raymond VI

had taken refuge in Toulouse and the Crusaders were prepared to smoke him out.

The population in the city was roughly divided between Cathars and Catholics.

The Catholic bishop of Toulouse, having fled to the Crusaders’ camp, now

demanded that the city’s Catholics refuse to obey the orders of Raymond VI and

expel him from the city. If they failed to follow this course of action the

city would be placed under interdict. Their proposals being rejected the city

was made lawful prey for the crusaders.

Simon de

Montfort was forced to lift the siege, as the Crusaders had come to the end of

the Forty days of service to the Cross. His reputation took a huge knock and

lifted the spirits of the heretics. As an alternative to attacking Toulouse the

Crusaders instead laid waste to the lands of the Count of Foix. In the spring

of 1212 new drafts of Crusaders arrived, giving de Montfort the advantage

again.

Chateau of the Comtes de Foix

Mopping Up

Raymond VI

and Raymond-Roger retired to the Aragonese court, leaving de Montfort in

control of the Languedoc. De Montfort had fallen out with Arnald-Amalric, who

had been promoted to Archbishop of Narbonne and had granted himself the title

of Duke. De Montfort summonsed an assembly in Pamiers which granted the church

many material advantages, but failed to give the clerics any role in

government.

De Montfort

was happy to leave the role of outing heretics to the church, while eager to

appropriate their lands. The Pope meanwhile was asking his legates why the

Count of Toulouse, still the rightful seigneur, had not been allowed to enter a

plea of self-justification. This letter of September 1212 was the result of

pressure from Raymond VI and his liege lord, the King of Aragon. The Pope

declared the crusade over and criticised the Legates and de Montfort for

excessive zeal;

‘Certain foxes were destroying the Vine of our Lord in

this Province. They have been caught…..Today

we have to prepare ourselves against a more formidable danger.’[vii]

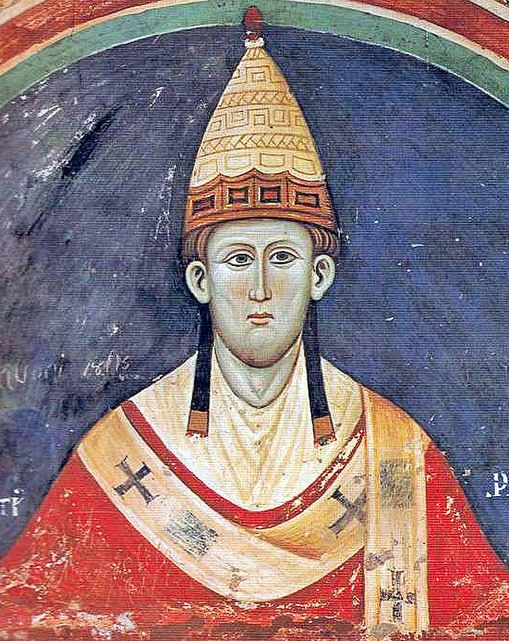

Peter of Aragon

The Legates

now faced a rather more formidable enemy; Peter II of Aragon who on 16th

July 1212 had beaten the Spanish Moors at the Battle of las Navas de Tolosa. As a champion of the church against

the infidel, Peter’s star was high in Rome. The people of Languedoc sent

representations to Peter requesting that he protect his sovereign rights in the

region. His son wrote;

‘The people of Carcassonne,

of Béziers, and of Toulouse came to my father and told him that only if he

would conquer them, he could become Lord of the Realm.’[viii]

Peter hoped

to divert the crusaders from southern France to fight against the Moors in

Spain. He viewed the crusade in Languedoc as a crusade against his sovereign

rights. Arnald-Amalric now threatened even this saviour of the church in Spain

with excommunication; the church in Languedoc could only be saved by preventing

the Count of Toulouse from regaining his rights.

The Pope,

acting on information from his vindictive Legates now threatened Peter with

‘Divine Wrath, and to take steps

against you such as would result in you suffering grave and irreparable harm.’[ix]

The church

in the middle ages could and did use their powers spiritual to direct the

temporal affairs of nations.

A strong

supporter of the church Peter was angered by the Pope’s attack and even more so

by the refusal to allow him to divorce his wife. In retaliation Peter gathered

an army of one thousand knights to conquer the Languedoc.

Battle of Muret

Peter’s army

besieged Muret but his death in the battle of Muret on 12th

September 1213 led to his men returning to Aragon. De Montfort’s victory meant

a crushing of Aragon’s power in France[x]. De Montfort now spent the

ensuing eighteen months mopping up isolated pockets of opposition to his rule.

He and the Legates were able to use the suspicion of heresy to make enormous

land grabs.

In January

1215 Raymond VI was dispossessed of his lands by the Council of Montpellier;

his lands were given to Simon de Montfort by the church, at the suggestion of

the Papal Legates. By the May the Dauphin Louis, on a

pilgrimage rather than a crusade which was now officially over, entered

Toulouse with de Montfort by his side. De Montfort had been wary of entering

the nest of vipers on his own.

As a token

of appreciation of his assistance Louis returned to Paris bearing with him the

jawbone of St Vincent. One of the side-effects of the crusade had been to

deflect crusader interest in Outremer, resulting in several years of peace in

the region. Sadly that was to change.

Bibliography

Massacre at

Montségur – Zoe Oldenbourg, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1989

Saint Louis

– Frederick Perry, AMS Press Inc, 1978

The

Thirteenth Century – Sir Maurice Powicke, University of Oxford Press 1988

The Templars

– Piers Paul Reid, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 2000

The Monks of

War – Desmond Seward, the Folio Society 2000

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

Some were neighbours or relatives. Later de Montfort’s brother Guy was to

return from crusading in the Holy Land to join him

[ii]

Not to be confused with Raymond-Roger, Viscount of Béziers, now deceased

[iii]

Montségur - Oldenbourg

[iv]

Ibid

[v]

Ibid

[vi]

Ibid

[vii]

Ibid

[viii]

Ibid

[ix]

Ibid

[x]

Peter’s son James was a four year old child

_vus_depuis_l'Est.jpg/450px-Le_ch%C3%A2teau_et_le_village_de_Termes_(Aude)_vus_depuis_l'Est.jpg)