Ieyasu’s wife formed a relationship with her Chinese doctor, plotting with Shingen against her husband and his ally Nobunaga. Evidence of the plot reached Nobunaga and Nobuyasu was implicated. Nobunaga demanded of Ieyasu that he order his son to commit suicide. Ieyasu took his son into custody and had his wife killed.

Nobuyasu committed suicide on 5th October 1579,

claiming that he was innocent of involvement in his mother’s plot. Ieyasu when

informed of the death, asked what make of blade had killed his eldest son and,

on being told Muramasa, replied

‘It

was with a Muramasa blade that Abe Yashichi struck down my grandfather

Kiyoyasu. And when I was a child at Miyagasaki in Suruga I cut myself with a

sword by accident, and that was a Muramasa blade, too. And now my son is killed

with one. Muramasa blades bode ill to our house. If any of you possess one he

had better get rid of it.’[i]

The Downfall of Takeda

|

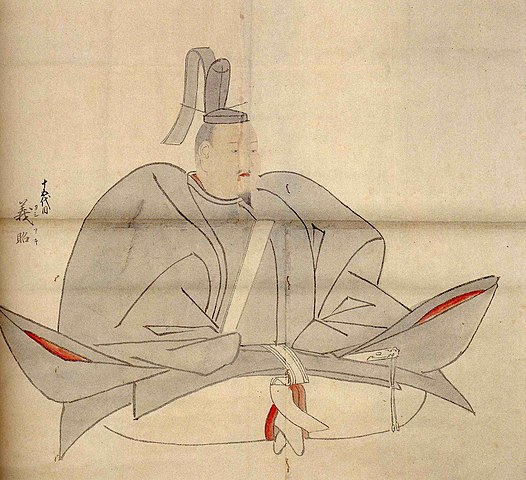

| Hojo Ujimasa |

In 1579 Takeda led an army of sixteen thousand against

Ieyasu, who had marched into Suruga, to co-operate with Hojo. Ieyasu returned

to Totomi and the skirmishing continued. The following year Ieyasu started besieging

his former border fortress of Takatenjin, obtained by Takeda by deception. By

the autumn of 1580 Ieyasu had prepared strong groundworks around the castle,

which was situated in difficult mountainous country. Takeda was advised against

attempting to relieve the siege.

By the following March some of the besieged tried to fight

their way out of the castle, resulting in a general attack by Ieyasu’s

besiegers. Takatenjin fell eight years after Takeda took it from Ieyasu’s men.

In December Takeda moved his capital to a castle near

Nirasaki; his people had become unhappy with his rule; his carelessness in

administrative matters and judicial decisions in direct contrast to his

father’s rule, had led to general disenchantment.

Oda Nobutada

At the beginning of 1582 one Kiso Yoshimasa proffered his

allegiance to Nobunaga. Takeda led an army against Kiso, but was unable to make

any headway in the mountainous countryside. Nobunaga now asked Ieyasu and Hojo

to take the field against Takeda. Nobunaga was engaged elsewhere, but his son

Nobutada led the Oda men.

As the allied force moved into Takeda territory, the

commanders of the forts defected to them[ii]. Out of a force of nearly

twenty thousand Takeda was left with three thousand; even two of his uncles had

left their posts, for safety in neighbouring provinces.

By March 1582 Nobunaga was able to join in the final attack

on Takeda, whose new capital was insufficiently advanced to defend. None of

Takeda’s friends and relatives attempted to support him, now that the hostile

forces were closing in. Takeda’s men fled in great numbers and he was

eventually left with immediate family and a few samurai. They were taken at

Tago. The women were killed and Takeda, his son and three brothers committed

seppuku.

After the Death of

Nobunaga

In June 1582 Nobunaga was murdered by a vassal, whom he had

insulted. Nobunaga’s son and heir died in the resultant fracas. Ieyasu had been

invited by Nobunaga to visit and following a six day stay, Ieyasu was taking a

leisurely tour in the environs of Kyoto, with a few retainers when he was informed

of the death of his ally. He made his way back to Okazaki with his retainers,

where he was informed that Hideyoshi had avenged Nobunaga’s death.

It was now that Ieyasu took control of Kai province after

the lord there was killed in an uprising, after he had killed one of Ieyasu’s

men, who had been sent offering free passage through Mikawa. This action

displeased Hojo, who now took his army of fifty thousand, pitting them against

Ieyasu’s seven thousand. Ieyasu’s generals outmanoeuvred Hojo’s men and Hojo’s

brother Ujinori, one of Ieyasu’s hostages, opened negotiations between the two

men, which resulted in Ieyasu keeping Kai and adding the province of Shinano.

Hojo received Kazusa and Ujinori was married to one of Ieyasu’s daughters.

The succession to Nobunaga was fought without the need for

Ieyasu’s intervention; he was too busy consolidating his new gains. He did

however send his congratulations to Hideyoshi on his victory over his rival.

Ieyasu was granted a promotion in Court ranks to the Upper Fourth and in 1584 a

further promotion to Lower Third level.

Ieyasu was now Lord of five provinces; Totomi, Mikawa,

Suruga, Kai and Shinano. Ieyasu allied himself with his neighbour Oda Nobuo in

Owari to the west and his eastern neighbour was his son-in-law Hojo Ujinori. To

the north was Hideyoshi, who offered Ieyasu a further two provinces if Ieyasu

would serve him; Ieyasu declined. Hideyoshi then attempted to de-stabilise

Nobuo, who appealed to his ally for help.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi

Hideyoshi was in the difficult position of being seen to act

against the son of his deceased lord and was uncertain of the reliability of

some of his allies. Hideyoshi was able to field an army of 25,000 in contrast

to the 30,000 of Ieyasu and his allies.

Hideyoshi agreed to a subordinate making a flanking move

behind Ieyasu, aiming at Okazaki. Ieyasu discovered the deception and marched

on the enemy. The resulting battle of Komaki ended with 2,500 of Hideyoshi’s

men dead to 590 of Ieyasu’s. Ieyasu returned to where the bulk of his army were

camped.

The two armies were stalemated. On the 1st May Hideyoshi

withdrew and invested Kaganoi in Nobuo’s province. Within six days he had

overcome the garrison and turned his attention to another castle, which took a

month to capture. His men overran Nobuo’s province. Nobuo responded to

Hideyoshi’s peace offer eagerly, without reference to his ally.

Having disposed of Nobuo, Hideyoshi now made advances to

Ieyasu, who agreed to allow his son O Gi Maru to be adopted by Hideyoshi[iii]. Hideyoshi then directed

his energies to quashing more of his antagonists in Shikoku and then moved on

Sasa Marinasa, a former Nobunaga general. Emerging from these disputes victorious,

Hideyoshi was able to isolate Ieyasu.

Isolation

Hideyoshi was happy to leave his most formidable antagonist

isolated, but he attempted to subvert some of Ieyasu’s subordinates. He

succeeded with Sanada[iv] and Ishikawa Kazumasa,

one of the foremost councillors of the Tokugawa and a companion of Ieyasu in

his childhood exile. Ishikawa’s defection, serious though it was, was not

followed by any of his fellow councillors. Ieyasu merely commented

‘Ishikawa

is disloyal to leave me, but we must not despise his military ability.’[v]

In the two years 1584 to 1586 the relationship between

Hideyoshi and Ieyasu stayed stable, although Hideyoshi’s power continued to

increase; he was named Kampaku in 1585, as he could not take the title of

Shogun. Ieyasu refused to entertain the idea of meeting Hideyoshi in Kyoto. In

January 1585 a deputation from the capital visited Ieyasu in Mikawa; where

Ieyasu was hawking. The deputation followed him and were roundly told off.

‘He

[Hideyoshi] can’t bring more than a hundred thousand men if he does come, and I

have thirty or forty thousand. But he doesn’t know the country about here and I

do. So if he risks it he’ll get the beating of his life. He seems to have

forgotten Nagakude pretty quickly. And as for you, I advise you to make

yourself scarce at once, or you will be in even greater danger.’[vi]

His unwelcome visitors departed post haste. A council of

Ieyasu’s retainers had already advised him not to submit to Hideyoshi.

Hideyoshi proposed that Ieyasu marry his half-sister; Ieyasu

laid down three conditions to the marriage which Hideyoshi accepted[vii]. The marriage changed

nothing in the relationship between Hideyoshi and Ieyasu, who decided to

strengthen his alliance with Hojo, visiting his province in March 1586.

Hideyoshi, about to deal with the Lord of Satsuma, now sent

his mother to visit her daughter at Okazaki, effectively making her Ieyasu’s

hostage, while Ieyasu met Hideyoshi at Osaka. If Ieyasu had not accepted the

invitation Hideyoshi had an alternate plan to blockade Ieyasu; knowledge that

Ieyasu presumably took into consideration when making his decision to finally

submit to Hideyoshi.

‘If

war breaks out again between us, well, you can never be absolutely certain of

the result, since the unexpected so often happens. And then we must consider

that it will mean more suffering for the people the longer it goes on, and what

would the loss of my one life matter compared with the avoidance of suffering

and death to so many innocent ones?’[viii]

Heroism or pragmatism? Ieyasu was a great pragmatist, so he

submitted to Hideyoshi.

Bibliography

Sekigahara – Anthony Bryant, Osprey Publishing Ltd 1995

Samurai William – Giles Milton, Hodder & Stoughton 2002

The Maker of Modern Japan – AL Sadler, Charles E Tuttle

Company 1983Tokugawa Ieyasu Shogun – Conrad Totman, Heian 1983

En.wikipedia.org

[i]

Ibid

[ii]

Apparently unusual in Japanese affairs

[iii]

He was given the name Hashiba Hideyasu

[iv]

A former supporter of Takeda Shingen

[v]

The Maker of Modern Japan - Sadler

[vi]

Ibid

[vii]

His current heir was to succeed him, no matter how many other sons were born to

Ieyasu, that he would inherit Ieyasu’s provinces and that his son and heir was

not to be sent as a hostage.

[viii]

The Maker of Modern Japan - Sadler