Before the SS

Born in Darmstadt on 13th

May 1900, Karl Freidrich Otto

Wolff was almost five months older than the man he was to serve so

faithfully, Heinrich Himmler. His father was a district court

judge and Wolff was raised as a Catholic, the two men sharing a similar

background.

|

| Freikorps recruitment poster |

But in one

respect Wolff was able to outshine his boss; in April 1917, having taken his arbitur, Wolff signed up to fight for his country. He underwent four months of

training and on 5th September 1917 volunteered to fight for Germany.

Wolff served in the exclusive Life Guards Regiment of the Grand Duke of Hesse, winning the Iron Cross second class[i]. He ended the war a lieutenant

and afterwards Wolff joined the Freikorps[ii].

Demobilised

in May 1920 Karl trained as a banker, undergoing a two year apprenticeship with

the Bethmann family bank in Frankfurt; the job found for

him by influential friends and relatives. Typically Wolff attached great

importance to living in a well-to-do neighbourhood, if possible renting from a

noble landlord. He later claimed that during this period of his life;

‘It was a constant battle to

avoid moving downward socially.’[iii]

Wolff got

engaged to Frieda von Römheld[iv] in July 1922 just as

Wolff was finishing his training. They both liked and were good at dancing,

winning a number of competitions. The couple married in August 1923. Wolff then

moved to work for the Deutsche Bank[v] in Munich after a brief period

working for a company his father-in-law had dealings with. But the

hyperinflation of the 1920’s resulted in the loss of his job at the end of June

1924.

Eventually

Wolff found himself a job in advertising working for Ad-Expedition Walther von

Danckelmann because he offered to work for the same amount he received from

benefit until he had proved his worth. Within a few months, having assimilated

sufficient of the finer points of advertising, Wolff was appointed manager of

one of the company’s branches.

On 1st

July 1925 Wolff left to set up his own company, using his wife’s name in the

company title; Ad-Expedition Karl Wolff - von Römheld. The agency was dissolved in

1931; Karl and Frieda Wolff were living in Bogenhausen, an upper-class Munich neighborhood, which doubled as the

family home and as the offices for company.

A New Life

On 7th

October 1931 at the Braunhaus[vi] Wolff joined the Nazi

party as member number 695131 and the SS

as member 14,325. Within three weeks Wolff went from being a raw recruit to the

lowest SS rank – SS-Schütze. On the 18th February 1932 he was

promoted to SS-Sturmfuhrer. At the time Wolff was attending an SS leadership

course; among the speakers were Himmler, Reinhard Heydrich[vii] and Franz Xaver Schwarz[viii] Later Wolff was to rhapsodise about

this first contact with Himmler;

‘The worldly seeds that were

then sown in our believing, open hearts later blossomed in a wonderful way and

bore fruit.’[ix]

He had

learned that the effusive the better for his Reichsfuhrer. After the end of

course party, for participants and their wives, Himmler insisted on giving the

Wolffs and Standartenfuhrer[x] Hoeflich[xi] a lift home.

In Power

Ritter von Epp

On the day

the Nazis came to power, 30th January 1933, Wolff was promoted to

the rank of Hauptsturmfuhrer[xii]. The Nazis did not have

control of all the Lander and in Bavaria Wolff and his men were used to create

incidents which presaged the takeover on 9th March. Wilhelm Frick, the Nazi Minister of the Interior[xiii], installed a Commissioner

in Bavaria. The new Commissioner, Ritter von Epp dismissed the police chiefs who were

replaced by Nazis.

Himmler was

given the post of Police President in Munich; not content with this sop Himmler

and his sidekick Heydrich schemed over the period March 1933 to spring 1934

patiently collecting the various political police of the Lander under his control[xiv].

Ludwig Siebert

From 9th

March 1933 Wolff worked as a personal adjutant for von Epp until mid-June[xv], when von Epp was

replaced by Ludwig Siebert. Von Epp offered Wolff another army

posting, but as this meant returning to his rank of Lieutenant Wolff accepted

Himmler’s offer of a job on his staff. He started on 15th June 1933,

becoming a full-time member of the SS. It was not until September that Wolff became

one of Himmler’s adjutants.

Moving On, Moving Up

At this time

Himmler’s chief of staff was Gruppenfuhrer[xvi] Seidel-Dittmarsch, who

was attempting to build his own power base; an attempt that ended with his

premature death in February 1934. Meanwhile Wolff was careering up the

promotion ladder; on 20th April 1934 he was given the rank of

Standartenfuhrer. The previous Christmas Himmler had given Wolff a photograph

of himself with a ‘very sincerely’

handwritten dedication.

Gestapo HQ on Prinz Albrecht Strasse

Wolff had no

direct responsibility in the Night of the Long Knives, when Himmler’s boss Ernst. Rohm, head of the Sturmabteilung or SA, was killed. As part of a quid pro quo in April 1934 Himmler was made

deputy head of the Prussian Gestapo[xvii] founded by Hermann Göring and Heydrich was placed in charge.

Wolff was

Himmler’s liaison with Göring, and while staying at the palace that was Göring’s workplace he must have heard

the endless streams of orders to kill Hitler’s enemies emanating from the

Reichsfuhrer and Heydrich as well as Göring.

Wolff

certainly benefitted from the resultant batch of promotions; he was made

Oberfuhrer[xviii]

on 4th July 1934. By now he was first adjutant to Himmler. Hitler

explained away his actions during the atrocity by saying;

‘If a mutiny broke out on

board a ship, the captain was not only entitled to but also obliged to crush

the mutiny right away.’[xix]

Himmler’s

reward for the involvement of his SS as the killing machine putting down the mutiny, was the removal of the SS from

hierarchy of the SA; Himmler now reported directly to Hitler.

Wolff met

Countess Ingeborg Maria von Bernstorff after the Night of the Long Knives. The

Countess came to ask for Himmler’s support for a charity. Wolff, with his

fascination for the nobility, flirted with the Countess[xx]. Her husband died the

following year and at some point the beautiful widow became Wolff’s mistress.

Like Himmler, Wolff had moved his family from Berlin to live at their home on

the Tegernsee.

Party Rallies

1934 Party Rally

At the

September party rally at Nuremberg Wolff played host to the members of the Freundeskreis der Reichsfuhrer SS[xxi] staying at the Grand Hotel.

Representatives of the Deutsche Bank, the Dresdner Bank, the Commerzbank, Flick

Steel and Siemens were among the companies that gave financial support to the

SS. The 1934 rally, stage managed by Albert Speer, was attended by a quarter of a million people.

By the end

of the year Wolff was persuading Himmler to see a healer to deal with his

headaches and stomach cramps[xxii]. Himmler spent much of

the summer of 1935 touring Germany, visiting the SS offices and speaking to his

SS men. He drove around in an open touring Maybach, usually accompanied by

Wolff and often by the wives of the two men. The two couples became close, indulging

in impromptu picnics and socialising together.

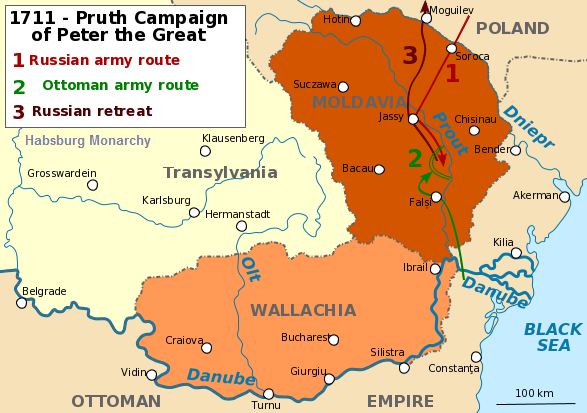

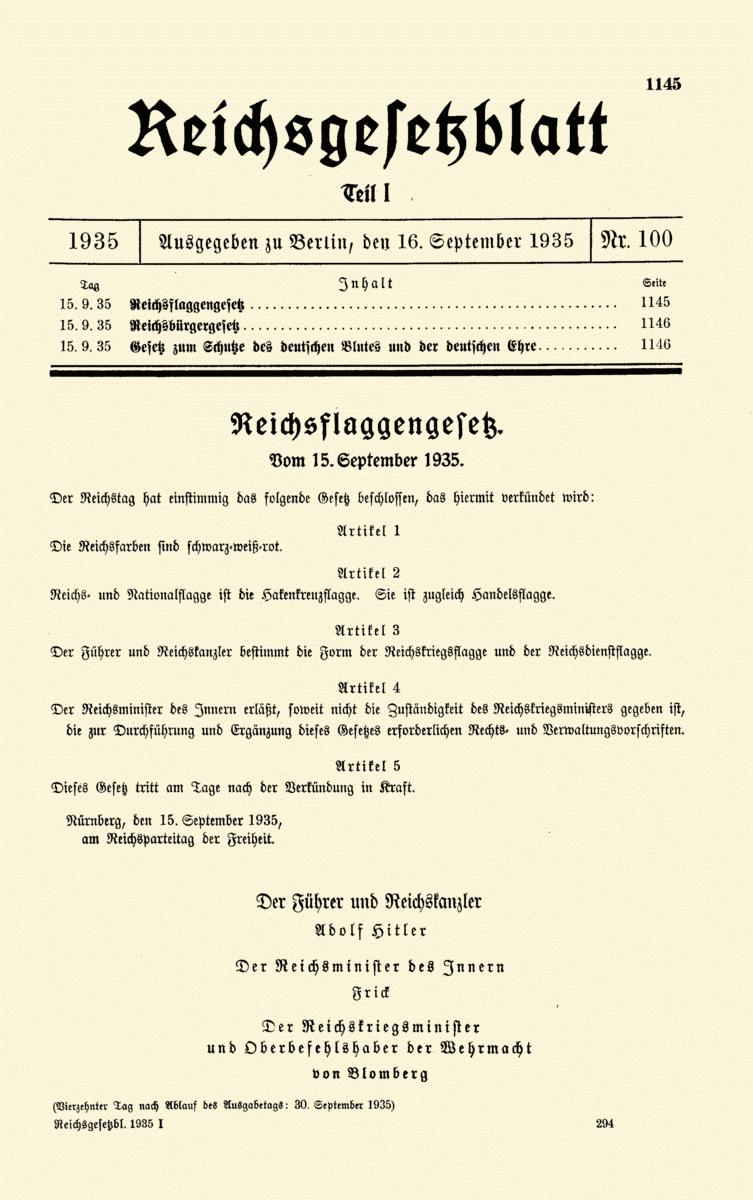

Title page of proclamation of Nuremberg racial laws

At the 1935

party rally Wolff was again hosting the members of the Freundeskreis RFSS as he

was to do at all subsequent rallies. It was at the 1935 rally that the infamous

Nuremberg racial laws were unveiled; aimed directly at the

Jews. Hitler claimed that this was a result of

‘Vehement complaints are

coming in from innumerable places about the provocative behaviour of individual

members of this people.’[xxiii]

Wolff and

Heydrich both visited the Himmlers at their home in Gmund on the occasion of

Himmler’s 35th birthday in October. Heydrich’s car broke down as the

families attempted to leave the party and Himmler was one of those who

push-started the car. The rivalry between Heydrich and Wolff was to grow over

the years; each jealous of the other’s influence over the Reichsfuhrer.

In November

1935 Wolff was made Chief Adjutant to Himmler and the following November

Himmler expanded his adjutants office into the Personalstab der RFSS; Wolf was

made Chief of Staff.

Bibliography

The Third

Reich in Power – Richard J Evans, Penguin 2006

The Order of

the Death’s Head – Heinz Hohne, Penguin 2000

The Black

Corps – Robert Lewis Koehl, University of Wisconsin Press 1983

Top Nazi –

Jochen von Lang, Enigma Books 2005

Heinrich

Himmler – Peter Longerich, Oxford University Press 2012

Allgemeine-SS

– Mark C Yerger, Schiffer Military History 1997

[i]

He later was given the Iron Cross First Class

[ii]

The Hessian Independence Corps

[iii]

Top Nazi - Lang

[iv]

Frieda’s father had been Chef de Cabinet to the last Grand Duke of Hesse

[v]

Whose record of association with the Nazi party and the SS was convoluted at

best

[vi]

The Nazi party headquarters in Munich

[vii]

Heydrich, in charge of the Sicherheinstdeist of the SS, had himself only joined

in June 1931

[viii]

Nazi Party Treasurer

[ix]

Top Nazi - Lang

[x]

Equivalent of a colonel

[xi]

Commander of 1st SS-Standarte; Wolff was head of Sturm 2 of the

Second Sturmbann of the Standarte

[xii]

Equivalent to captain

[xiii]

In charge of security

[xiv]

In June 1936 Himmler was made Chief of the German Police giving him control of

the security apparatus of the state; a job that was to bring him immense power

[xv]

Himmler gave anyone of any importance, whether belonging to the SS or not (von

Epp did not) SS aides to increase the scope of his intelligence apparatus

[xvi]

Equivalent in rank to a Major General

[xvii]

The Prussian political police

[xviii]

A rank that has no army equivalent, but placed between Colonel and Brigadier

General

[xix]

The Third Reich in Power - Evans

[xx]

The daughter of a businessman.

[xxi]

Originating as a group to fund Hitler’s projects, this group now did the same

for Himmler. The group included senior officials from German banks and

industrial complexes

[xxii]

These stomach cramps would debilitate Himmler throughout the rest of his life

[xxiii]

The Third Reich in Power - Evans

.jpg)