|

| Pavlovsk Palace |

Trip to Russia

Dorothea’s deferred trip to Russia finally got underway in

June 1825. She arrived in July and stayed at the Pavlovsk Palace where

the dowager Empress held her court. Dorothea found it difficult to re-adapt to

the more formal behaviour required in the Russian court. As Czar Alexander lived

as a recluse at Tsarkskoe Selo with his wife, court life centred round Maria

Feodorovna.

.jpg) |

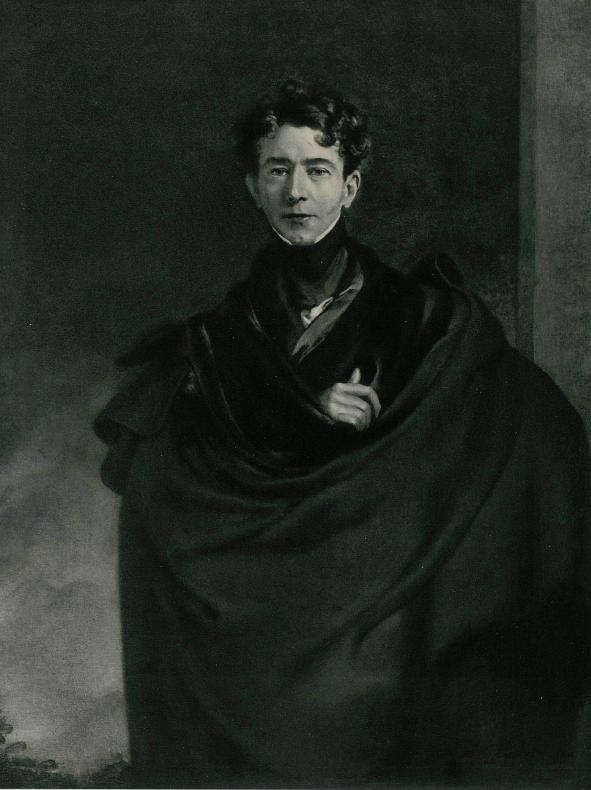

| Czar Alexander I |

During her visit Dorothea had a 1½ hour meeting with

Alexander; she took advantage of the meeting to deliver a critique of

Metternich and Austrian policy. She then had a meeting with Count Nesselrode. That

both Alexander and Nesselrode knew of her affair with Metternich only made them

take her opinions more seriously. Following the meeting Alexander commented to

Dorothea’s brother;

‘Last

time I saw your sister she was an attractive girl; now she is a stateswoman.’[i]

A second interview with Alexander towards the end of

Dorothea’s stay saw Alexander ask her opinion of Canning, whom he described as

a Jacobin. On 19th August, immediately prior to her departure, Dorothea

saw Nesselrode again; he informed her that Alexander believed that following

Metternich’s advice over Greece benefitted only Austria. The Czar wanted to use

Dorothea to persuade the English to open overtures with Russia. Dorothea asked

for and received a note for Christopher informing him of this drastic change in

Russian policy.

Back Home

|

| Royal Lodge, Windsor |

Dorothea’s return journey to England took a month and she

arrived back in September. The speed of the journey so exhausted her she had to

rest for ten days in Brighton, seeing no-one but Canning and Wellington.

Dorothea wrote to Alexander about her problem child;

‘I

am delighted to hear that my mother-in-law is interesting herself in

Constantine’s future, and I shall be most anxious to hear what becomes of her

care.’[ii]

In October the Lievens stayed with the King in the Cottage at Windsor.

Encouraged by Dorothea, George invited Canning to dinner and Canning was able

to amuse the King. Dorothea viewed Canning as her protégé and advised him on

court etiquette and international affairs. Canning was surprised to be visited

by the Lievens on 24th October. They gave Canning details of the

disagreements between Russia and her allies over Greece.

|

| Czar Nicholas I |

Then disaster struck; Czar Alexander died on 1st

December 1825 to be replaced by his brother Czar Nicholas,

the youngest of Dorothea’s mother-in-law’s charges. Dorothea was devastated,

well aware that the new Czar would not entrust her with the responsibilities

Alexander had;

‘I

cannot sleep I can only weep, I weep from the bottom of my heart, all is over.

He [Alexander] gave me a new interest in life. I had great political influence

over him ad I should soon have had more.’[iii]

Christopher was recalled to Russia in March. Dorothea was

concerned that Nicholas might want to keep Christopher in Russia.

‘He

likes my husband, and respects him, and he likes and respects scarcely anybody

else in the world….my husband will resist all proposals. He has not a spark of

ambition in his make-up.’[iv]

With Christopher absent in Russia, Dorothea played the part

of Russian ambassador from the new Russian embassy at Ashburnham House.

Canning sent Wellington to St Petersburg with detailed

instructions; he was tasked with dissuading the new Czar from going to war with

the Turks over Greece. Being unwell only added to Wellington's disinclination to

visit Russia. He went very unwillingly and arrived in March 1826.

Canning ordered Wellington to urge that the Lievens be kept

on in London. On 4th April 1826 Wellington signed the Protocol of St

Petersburg[v] before returning home. He

arrived back to find Dorothea and Christopher had been reporting unfavourably

upon his actions in St Petersburg.

Social Elevation

When Wellington’s sister-in-law[vi] returned from Vienna in

the spring of 1826 she brought home unwelcome news for Dorothea. Metternich had

taken to visiting one Mademoiselle Antoinette von Leykam, a 19 year old who was

to become his second wife the following year. Dorothea was cutting in her

correspondence with Metternich.

Bored with the grasping Lady Conyngham, it was now that the

king suggested that Dorothea became his mistress, having summonsed her down to

Brighton, claiming;

‘[He

had] been in love with me for thirteen years.....never dared tell me; he hoped

I should find it out for myself......[she] alone could guide him; our minds are

alike; our views agree; my tastes will be his.’[vii]

In Russia Dorothea’s family were the willing recipients of

the new Czar’s patronage. Alexander von Benckendorf became head of the Russian

secret police and was one of Nicholas’ key advisers and Christopher became a

Prince when his mother was awarded the rank of Princess for her services to the

royal family. Alexander von Lieven was hoping to be appointed to the United

States Mission that his father had been under consideration for.

Dorothea’s elevation brought a spat with Princess Esterhazy;

the two had never cared for one another. Now the waning of Dorothea’s

relationship with Metternich meant the wife of the Austrian ambassador could

vent her dislike, her public put-down of Dorothea at a party at Wellington’s

house was greeted with general approbation. Princess Esterhazy was good-natured

and well liked while the witty and sharp Dorothea was not popular.

Rising Star

Dorothea wrote her last letter to Metternich on 12th

December 1826. When she heard that he had married the beautiful Mademoiselle

Leykam, a bitter Dorothea commented unpleasantly that it was a shame that;

‘[The]

Chevalier of the Holy Alliance had ended by concluding a mésalliance.’[viii]

|

| Mrs Arbuthnot |

Dorothea was at a crossroads and, in a complete volte-face,

she now decided to befriend the rising star. Her political courtship of Canning

caused amusement among those like Harriet Arbuthnot[ix]

who could not forget that Canning’s mother was an actress. Mrs Arbuthnot

attributed Dorothea’s political change of heart to the break-up of her

friendship with Metternich.

Dorothea was of course now following the political star of

one who wanted to undo much of what Metternich had wrought. Her conversion was

viewed with disapproval; Canning was viewed as a dangerous liberal who would

bring down revolution upon Europe. Her support of Canning also led to a break

with Wellington. But Dorothea supported Canning because his policies coincided

with Russian interests.

Christopher was busy getting Canning to support a policy

opposed by the majority of the British cabinet. Dorothea found support for

Canning’s idea of a solution to the Greek question in Lord Grey, who might be

persuaded to prop up a Canning government.

Prime Minister

|

| Sir Robert Peel |

Liverpool suffered a stroke in February 1827 and George

appointed the detested Canning as Prime Minister. Refusing to serve under

Canning’s leadership, Wellington resigned as Master of

the Ordnance and Commander in Chief of the armed forces.

Sir Robert

Peel and other senior Tories also refused to work with the detested but

brilliant Canning who had to rely on the support of the Whigs to remain afloat.

Dorothea lent Canning her support and even discussed and approved of the

appointment of Lord Dudley

as Foreign Secretary.

Mrs Arbuthnot noted Dorothea’s activities in the enemy camp

with a growing dismay;

‘She

has gained great influence over Mr. Canning and

Lord Dudley and she manages

Lieven as she pleases……it is curious enough that the loves and intrigues of une femme galante should have such an

influence over the affairs of Europe.’[x]

|

| Lord Dudley |

Mrs Arbuthnot was wrong; Dorothea was having problems with

Christopher; she told her brother that her husband ignored the fact that she

was suffering from palpitations of the heart. Dorothea wrote to Christopher

accusing him of no longer loving her. Christopher was not one for emotional

scenes and her letters probably caused him acute embarrassment. To add to

Dorothea’s troubles news about Constantine failed to arrive despite continued

requests in her letters to her brother.

Disaster

|

| Naval base Portsmouth |

Canning’s own health was not good and he had to expend much

of his energies to keep his disparate cabinet working together. He died in the

July, three months into his new job[xi]; Dorothea was greatly

distressed by Canning’s death and it made her ill. She was unable to accompany

Christopher to meet the Russian fleet which called into Portsmouth en route to the Mediterranean. Never one

to under dramatize a situation Dorothea informed her brother;

‘My

husband has started for Portsmouth to see our fleet, and I, very ill, am left

behind. I was dying to see Russia again, but the wish could only be gratified

at the risk of killing myself.’[xii]

The Turks had been given one month to accept the mediation

of the great powers in its quarrel with Greece. Failure to do so would result

in the recognition of Greek independence.

|

| Duke of Devonshire |

Dorothea took herself off to Chatsworth for the Doncaster races. The

party included the Cowpers and Mr and Mrs Agar

Ellis. The race meeting itself brought more friends; Lord Grey, Lord

Worcester and Lord

Londonderry. Christopher joined the group and immediately the pair were

quarrelling again, writing notes to one another on disputed trivialities. Dorothea

played the sympathy card once again;

‘Decide

whether you can sacrifice your puerile vanity for the reasons I have given you,

otherwise I must ask you to arrange that I can live apart from you…..I have

just had a haemorrhage…..I think that you want at all costs to humiliate me and

to tease me.’[xiii]

These dramatics were over the question as to whether

Christopher should wear a red ribbon the Duke of Devonshire had requested he

wear. Dorothea had assured him his host was making fun of her husband.

Christopher was prepared to humour the Duke’s ‘enfantillage’ and Dorothea was infuriated. The couple returned to

London in October but the infighting continued.

Bibliography

The Princess and the Politicians – John Charmley, Penguin

Books 2006

Wellington – Christopher Hibbert, Harper Collins 1997

Paris Between Empires – Philip Mansel, Phoenix Press

Paperback 2003

The Life and Times of George IV – Alan Palmer, Book Club

Associates 1972

Princess Lieven’s Letters – Lionel G Robinson (ed),

Longmans, Green & Co 1902

The Russian Empire – Hugh Seton-Watson, Oxford University

Press 1988

Metternich – Desmond Seward, Viking 1991

Arch Intriguer – Priscilla Zamoyska, Heinemann Ltd 1957

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

Arch Intriguer - Zamoyska

[ii]

Princess Lieven’s Letters - Robinson

[iii]

Arch Intriguer - Zamoyska

[iv]

Ibid

[v]

Allowing for British and Russian mediation with the Turks on the Greek

question.

[vii]

The Princess and the Politicians - Charmley

[viii]

Ibid

[ix]

A Tory party hostess

[x]

Arch Intriguer - Zamoyska

[xi]

He had never recovered from an illness picked up while attending the Duke

of York’s funeral in January

[xii]

Princess Lieven’s Letters - Robinson

[xiii]

Arch Intriguer - Zamoyska