|

| Charles and Pepin the Hunchback |

Conspiracies Abound

In 786 a

conspiracy was uncovered, centred in the north-east of Francia. These lands had

borne the brunt of the majority of the campaigning against the Saxons. One

Count Hardrad and his neighbours planned to kidnap Charles to extract more

rewards for their services to the crown. The plot was betrayed and three of the

conspirators were executed while the remainders had their eyes put out and were

shut up in monasteries.

In 792

another conspiracy came to light involving Charles’ illegitimate and firstborn

son Pepin the Hunchback and a number of the Frankish nobility. Pepin felt that

he’d been denied his birth right as Charles’ eldest son. When the call came to

attack the Avars Pepin claimed to be sick and stayed home. He planned to raise

large numbers of supporters while Charles was away and proclaim himself king.

There were a

significant number of Frankish nobles concerned about the autocracy Charles had

created. A young monk overheard the plotters and reported the conspiracy to

Charles. The supporters were rounded up and charged with violating their oath

of allegiance to Charles and his family. The rebels claimed they’d never been

asked to swear the oath;

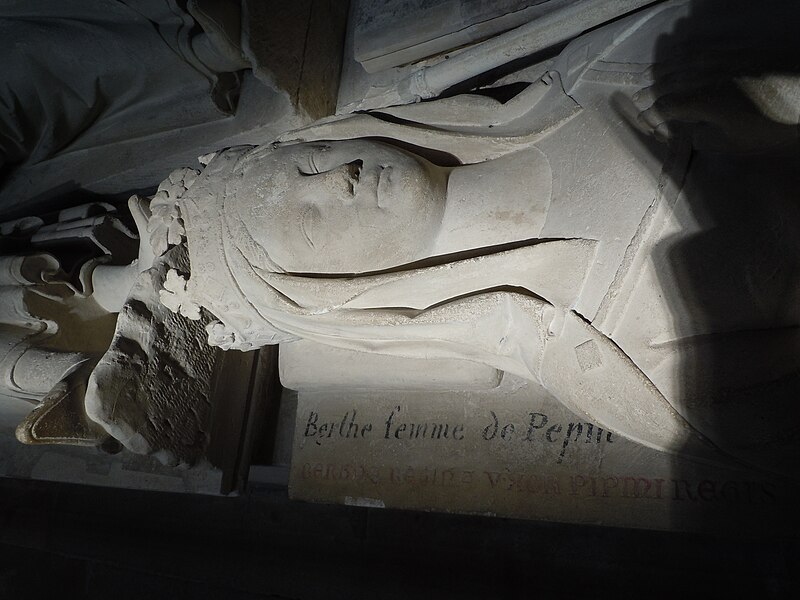

|

| Relic from Prum Abbey, given to Pepin's grandfather |

When Charles, after the

beginning of the war against the Huns, was wintering in Bavaria, this Pippin

pretended illness, and formed a conspiracy against his father with some of the

leaders of the Franks, who had seduced him by a vain promise of the kingdom.

When the design had been detected and the conspirators punished Pippin was

tonsured and sent to the monastery of Prumia, there to practise the religious

life.’[i]

Following the quelling of the rebellion Charles summonsed an assembly at

Regensburg and the nobles present adjudged Pepin and his adherents guilty and

discussed the political consequences of rebelling against the throne. Most of the conspirators were

beheaded while Pepin was sent to the monastery of Prüm.

Family Affairs

|

| Coin depicting Offa |

Around 789,

Charles proposed that his son Charles the Younger marry Ælfflæd, the daughter of King Offa of Mercia. Offa insisted that the marriage could only go ahead if Charles’

daughter Bertrada married Offa's son Ecgfrith. Charles took offence, broke off

contact, and closed his ports to English traders. Eventually normal relations

were re-established and the ports were reopened.

Fastrada

died on 10 August 794 in Frankfurt, Germany, during the synod of Frankfurt.

She was buried in St. Alban's Abbey, Mainz, long before the building was finished. Einhard had no great

opinion of Fastrada[ii];

talking of the two conspiracies against Charles he recorded;

‘The cruelty of Queen

Fastrada is believed to be the cause and origin of these conspiracies. Both

were caused by the belief that, upon the persuasion of his cruel wife, he had

swerved widely from his natural kindness and customary leniency’[iii]

Einhard

attempts to throw all the blame for any claims of cruelty onto Fastrada. His

claims that Charles was unnaturally kind to all and sundry are not true; he did

give way to his temper at times, kind kings do not usually reign long in

turbulent times.

Charles,

from the very beginning, had decided he would do whatever was necessary to keep

himself on the throne of Francia, stamping his will on his subjects. He is

unlikely to have been influenced by Fastrada, who was only 21 at the time of

the first conspiracy. Einhard’s embellishing of Charles’ reputation was part in

justification of his new master’s right to rule after his father.

Charles was

an unusually tall man for the age; Einhard informs us that he was seven times

the length of his feet high[iv].

It is likely that he towered over most of the other men at court, useful for

dominating those around him.

Not long

after Fastrada’s death Charles married Luitgard, his last wife who died childless six years later in 800. The same year

Charles picked a concubine named Regina who had two sons, Drogo[v] born in 801 and Hugh[vi] in 802. Charles’ final concubine was

Ethelind who gave him two sons, Richbod[vii]

in 805 and Theodoric in 807 who died the same year as his birth.

Death of a Pontiff

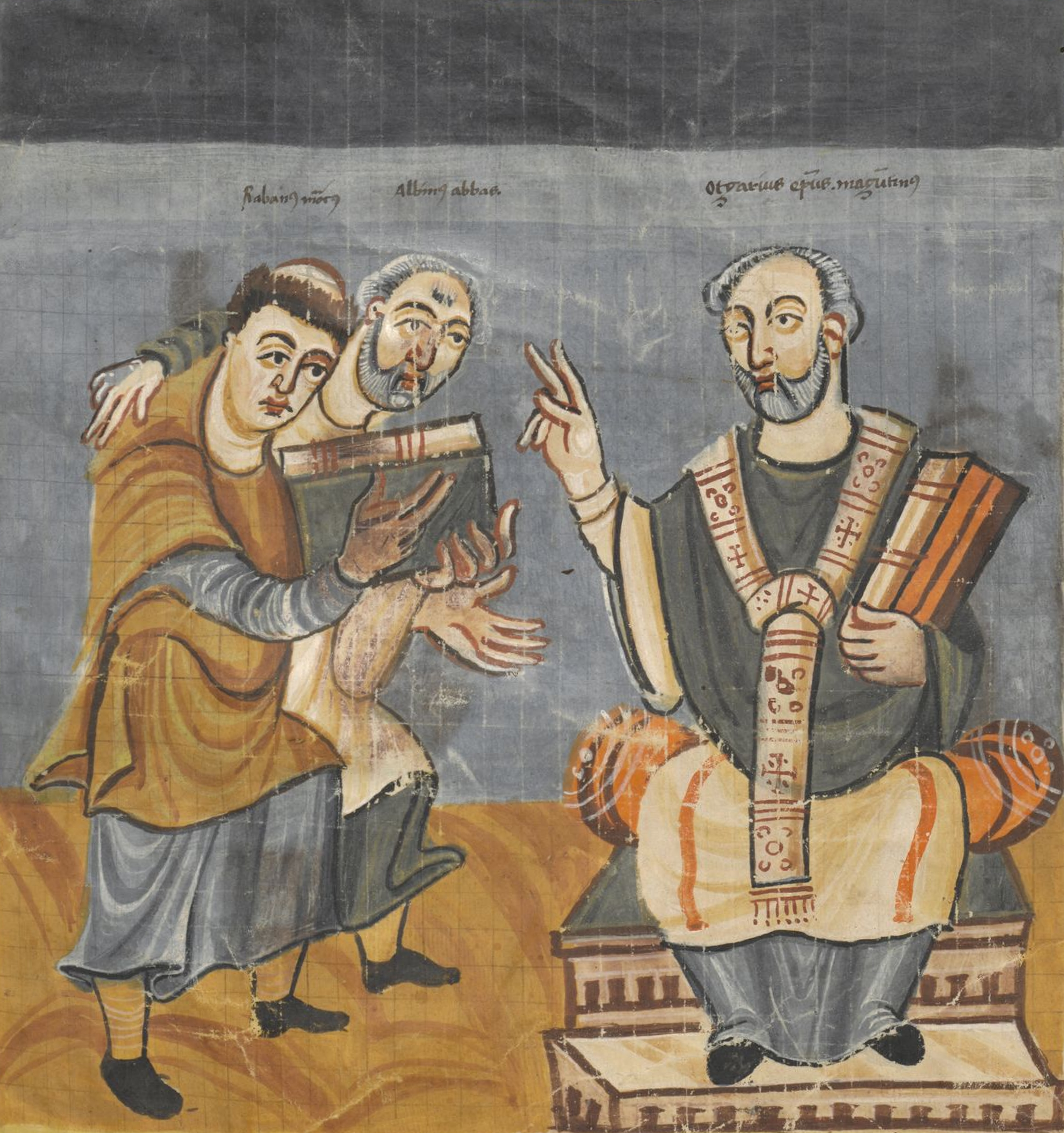

|

| Leo III |

On 25th

December 795 Pope Hadrian died; Charles sorrowed at the death;

‘When the death of Hadrian,

the Roman Pontiff, whom he reckoned as the chief of his friends, was announced

to him, he wept for him as though he had lost a brother or a very dear son.[viii]

Hadrian and

Charles had worked together for twenty three years[ix];

the pair established a relationship built on mutual respect and affection.

Hadrian was appreciative of Charles’ support in protecting the papal estates.

In Francia Charles had involved himself in church affairs, writing to bishops

about clerical morals, discussing points of doctrine with theologians and

deciding who to appoint to the dioceses he carved out in his kingdom. Charles

refused to augment papal authority and refused to be used as a stick to beat

Hadrian’s enemies.

Pope Leo III was elected on the 26th

December that Hadrian was buried and was consecrated on the following day[x].

Leo wrote to Charles informing him that he had been unanimously elected pope.

With the letter Leo enclosed the keys of the confession of St. Peter, and the

standard of the city, and requested an envoy. His letter was an assurance that

Charles was viewed as the protector of the Holy See.

Emperor of the Romans

|

| Leo III meets with Charles |

In Byzantium

in the summer of 797 the Empress Irene deposed her son Constantine VI, in

retaliation for his having banished her in 790. Her supporters captured and

blinded him[xi];

Irene then made herself Empress Regnant. This action by a mere female was to have wide-ranging repercussions.

On 25th

April 799 Pope Leo was ambushed by a group of Roman nobles[xii]

who attempted to put Leo’s eyes out and cut out his tongue[xiii].

He managed to escape and fled to Charles who was holding court at Paderborn,

preparing for another war against the Saxons. Leo returned to Rome in November

and was accused by his enemies of simony, perjury and adultery among other crimes.

In November

800 Charles travelled to Rome where he met with both parties to the quarrel. Alcuin

had been talking for some time of Charles’ imperium

and had recently written to Charles reminding him that Empress Irene’s actions

had upset the world order; females were incapable of ruling and so Irene was

not able to be Leo’s judge. In Alcuin’s eyes that role should fall upon the

male and very capable Charles.

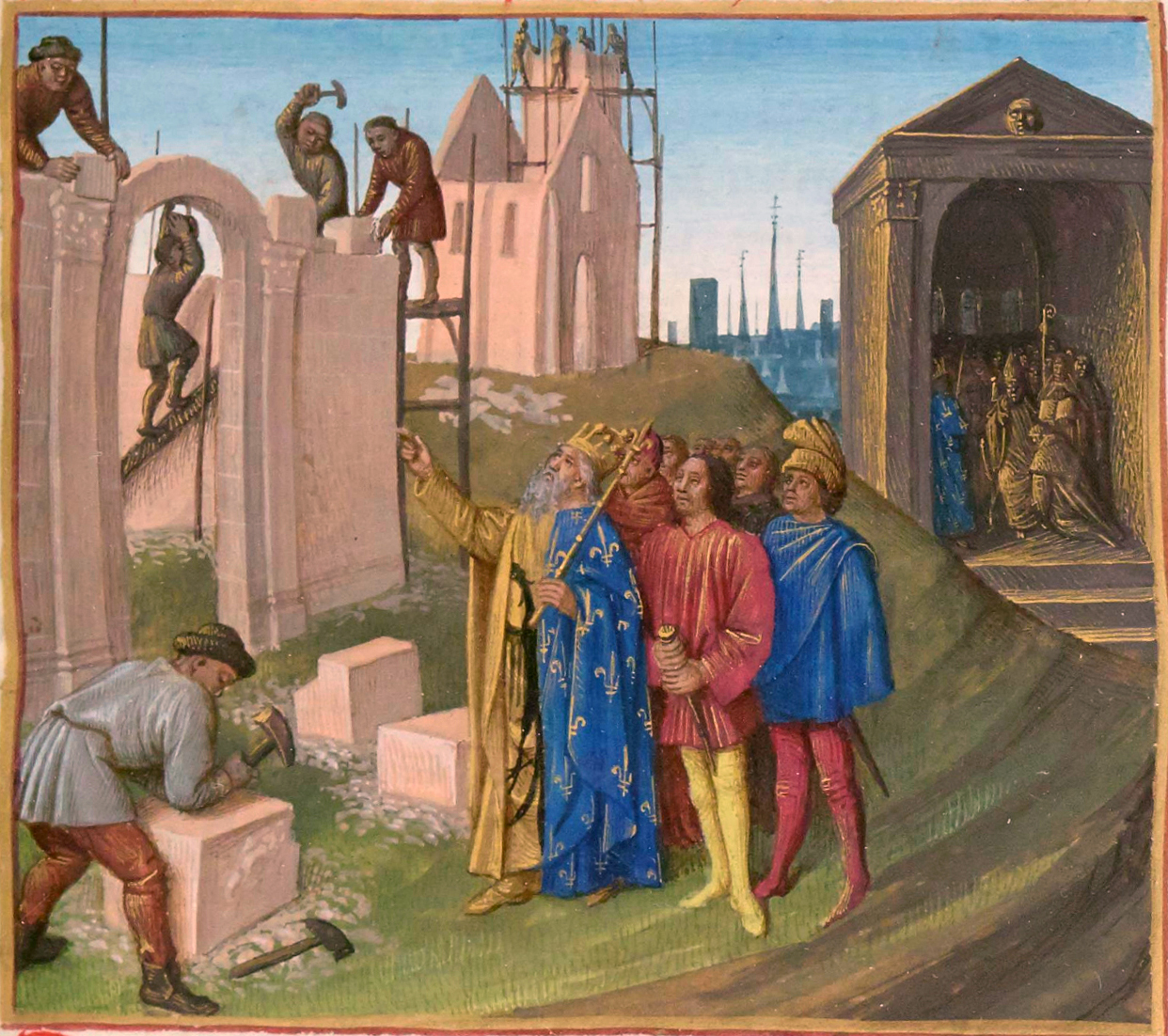

|

| Leo crowns Charles as Emperor |

On 23rd

December at the high altar Leo swore that he was not guilty of the crimes

charged against him. That he was not instantly struck down by a thunderbolt (or

similar) from God was clear proof of his innocence. On 25th

December, two days after taking the oath in an allegedly surprise move, Leo

crowned Charles Emperor of the Romans[xiv].

‘He therefore came to Rome

to restore the condition of the church, which was terribly disturbed, and spent

the whole of the winter there. It was then that he received the title of

Emperor and Augustus, which he so disliked at first that he affirmed that he

would not have entered the church on that day—though it was the chief festival

of the church—if he could have foreseen the design of the Pope.’[xv]

There has

been much debate about the significance of this coronation and as to whether

Charles was quite as surprised as Einhard claimed. There had been plenty of

time in Paderborn for Charles and Leo to discuss the possibility and may have

been a quid pro quo for Charles acceptance of Leo’s oath that he was innocent

of the charges made against him.

Piggy in the Middle

.jpg/323px-Irina_(_Pala_d'Oro).jpg) |

| Empress Irene |

Charles elevation

to the imperium greatly offended the rulers of Byzantium who refused to accept

the division of the old Roman Empire into east and west. They took Charles’

actions in Italy as encroachment on lands that divided the two empires.

Charles had

no intention of attacking Byzantium; he may have hoped for submission from

Irene whose rule was not popular among her nobles and officials. Rumours of a

marriage between the Empress and the barbarian swirled around Constantinople

and led in part to a palace coup headed by Irene’s chancellor Nicephorus in 802[xvi].

For the rest

of Charles’ reign a state of cold war existed between the two empires;

Nicephorus and his successors were suspicious of Charles’ motives;

‘The Emperors of

Constantinople, Nicephorus, Michael, and Leo, too, made overtures of friendship

and alliance with him, and sent many ambassadors. At first Charles was regarded

with much suspicion by them, because he had taken the imperial title, and thus

seemed to aim at taking from them their empire.’[xvii]

In 803

Nicephorus sent a peace delegation to Charles; the two empires had exchanged

ambassadors the previous year. But the Byzantines encouraged the city of

Benevento to throw off its Frankish overlordship. King Pepin launched campaigns

in 801 and 810 but neither was successful. In 802 the Duke of Benevento

captured Winigis, one of Charles’ most trusted

lieutenants, at the siege of Lucera.

Bibliography

Celts and Saxons – Peter Berrisford Ellis, Constable and Company Ltd

1995

The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages – Robert Fossier

(ed), Cambridge University Press 1989

The Holy Roman Empire – Friedrich Heer, Phoenix 1999

The Oxford History of Medieval Europe – George Holmes, Oxford University

Press 2001

The Year 1000 – Robert Lacey & Danny Danziger, Abacus 2007

Absolute Monarchs – John Julius Norwich, Random House 2011

Emperor of the West – Hywel Williams, Quercus 2010

Charlemagne – The Great Adventure – Derek Wilson, Hutchinson 2005

[ii]

He was writing during the reign of Charles’ son and successor who can have been

only too willing to allow his stepmother to take the blame for the problems

Charles faced during the period

[iv]

His skeleton was measured in 1861; Charles was 6’ 5”

[vii]

Later Abbot of St Riquier

[ix]

One of the longest reigning pontiffs

[x]

It is possible that this haste was

due to a desire on the part of the church to forestall any interference by the

Franks with their freedom of election

[xi]

It is believed that he died shortly thereafter

[xii]

Led by Hadrian’s nephew; Hadrian’s family, one of the Roman noble families, had

apparently expected that one of their number would receive the papal tiara

[xiii]

Which would oblige Leo to renounce the papacy

[xiv]

Or Holy Roman Emperor