|

| Count Fulk's seal |

Henry began

to formally look for a new husband for Matilda in early 1127 and received

various offers from princes within the Empire. In 1128 Matilda was

wed to the handsome fifteen year old son Geoffrey, son of Fulk of Anjou. Henry was

still intensely interested in the power of the Counts of Anjou and desperate to

offset William Clito’s standing.

Fulk was

turning his eye east towards Jerusalem, where Fulk had interests. He had joined the Knights Templar in 1119/20 when on crusade and had remarried to Melisande, the daughter of Baldwin II, the King of Jerusalem. Fulk had already abdicated his

County of Anjou in Geoffrey’s favour.

|

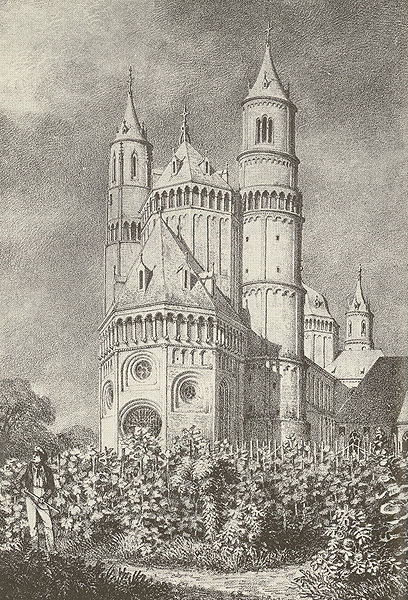

| Le Mans cathedral |

The marriage

between Matilda and Geoffrey took place on 17th June 1128 in Le Mans cathedral.

Geoffrey was knighted by his future father-in-law the week before the wedding.

‘The king sent his daughter into Normandy, ordering her to be betrothed, by

the archbishop of Rouen, to the son of Fulco aforesaid, a youth of high

nobility and noted courage. Nor did he himself delay setting sail for Normandy,

for the purpose of uniting them in wedlock.’[i]

Matilda was

eleven years senior to her new husband and the marriage was very unhappy.

Matters were not aided by the fact that Matilda insisted on speaking only

German while Geoffrey spoke French.

Domestic Matters

There was

much mutterings about the royal marriage, with a number of the nobility and

churchmen claiming that the marriage relieved them of their oath over the succession,

as recorded by William of Malmesbury;

‘All declared prophetically, as it were, that, after his death, they would

break their plighted oath. I have frequently heard Roger, bishop of Salisbury,

say, that he was freed from the oath he had taken to the empress: for that he

had sworn conditionally, that the king should not marry his daughter to any one

out of the kingdom without his consent, or that of the rest of the nobility.’[ii]

|

| Postern gate of Northampton Castle |

At one point

early on in the marriage Matilda left Geoffrey, returning to her father’s court

in Rouen while Geoffrey announced his determination to go on

pilgrimage to the shrine of St James at Santiago di Compostela. Henry appears to have blamed

Geoffrey for the separation, but Henry summoned Matilda from Normandy, and she

arrived in England that August.

A meeting of

the King's great council was called by Henry; the council met at Northampton castle on

8th September 1129. It was decided that Matilda would return to

Geoffrey; Henry must have been loath to lose this new alliance. The council

also gave another collective oath of allegiance to recognise Matilda as Henry's

heir. This action seems to have caused a turning point for Matilda who

henceforth supported her husband against her father.

On 5th

March 1133 the Matilda gave birth at Le Mans to the couple’s first son Henry[iii]. They were to have three children,

the second child Geoffrey[iv] was born on 11th June

1134 at Rouen, a difficult birth during which Matilda nearly died. King Henry

was at his daughter’s bedside as she ordered the arrangements for her bequests

and burial in the abbey of Bec[v].

Death of a King

|

| Henry I |

In the

autumn of 1135 King Henry arrived at his castle in Lyons-la Fôret for the purpose of hunting. He was

68; William of Malmesbury claims the king fell sick during the hunt, Henry of Huntingdon claimed that Henry was heartsick

that his daughter supported her husband over her father over the issue of her

dowry, a number of castles in Normandy. Henry refused to hand over control of

the castles to Geoffrey causing a rift between the two courts[vi].

Orderic claims Henry became sick the night

before and then generally worsened over the next few days. Henry authorised his

bastard son Robert of Gloucester to take £60,000 to pay the soldiers and

servants and gave instructions that he was to be buried at the Abbey[vii] at Reading. When queried about his successor Henry;

‘Assigned all lands on both

sides of the sea to his daughter in lawful and lasting succession.’[viii]

|

| Donjon of Argentan |

Henry was still

apparently ‘somewhat angry’ with

Geoffrey, who failed to pay him sufficient respect.

Whatever the

cause, on 1st December Henry died leaving his daughter the Countess

of Anjou as his nominated heir. Matilda immediately rode north to seize the

border castles of Domfront, Exmes and Argentan. Geoffrey was unable to come to her

aid as he was detained by a rebellion in Anjou and while Matilda was again

pregnant. She established herself in the chateau at Argentan where she gave

birth to her third child William, born on 22nd July 1136

The Race for the Crown

A

significant number of those who swore to support Matilda as ruler of the realm

switched allegiance when another contender for the throne arose. Matilda’s

cousin Stephen laid claim to the throne for himself, foreswearing the oath he

had made seven years before. Stephen had been of use to his uncle on the

diplomatic and military stage of northern France for some years.

Now Stephen

quickly made peace and came to terms with Henry’s greatest enemy William Clito

and. He was well-known to those of import in both England and Normandy, whereas

his cousin Matilda had lived most of her life in either Germany or now Anjou.

|

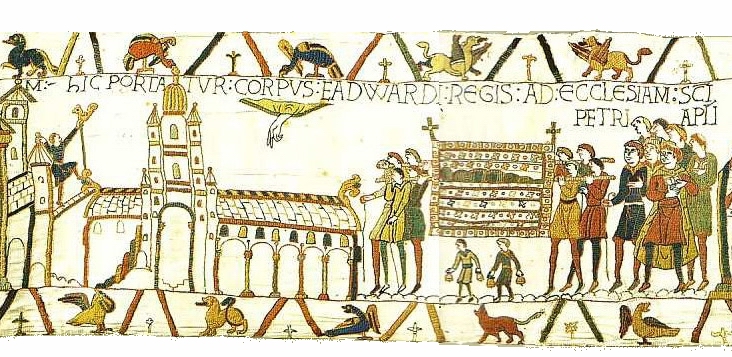

| Westminster Abbey (L) |

It was all

to be decided at the end of the day by a question of who would be first to be

crowned monarch of England, Stephen[ix] or his cousin Matilda,

who may have been impeded by her pregnancy from making the cross channel dash .

Stephen received the news of his uncle’s death when he was in Boulogne and by

the 5th December he had crossed the channel to England and was

crowned king on 22nd December at Westminster Abbey;

‘Stephen, count of Boulogne,

having been chosen by the nobles of the kingdom, with the sanction of the

clergy and people, was crowned king in London on Christmas Day[x],

by William, archbishop of Canterbury.’[xi]

Once he’d

been acclaimed king in London Stephen travelled post haste to Winchester, the administrative centre of the kingdom. He also stood in

Matilda’s place as chief mourner at Henry’s lavish funeral.

Tied up in Knots

In contrast

with Matilda’s prickly mien, Stephen was an affable man who got on with people;

not a failing Matilda ever suffered from. He also benefitted from a public backlash

against Henry’s harsh governance. Stephen promised to revert to the laws of good king Edward. It was Stephen’s own affability

that tied him into knots; he had to promise much to his supporters. The

Londoners agreed to support him as long as he brought peace to the land, a

promise Stephen would find hard to keep.

|

| Henry of Blois |

Stephen was

also supported by the church in the person of his brother Henry of Blois[xii] who Stephen described as being the

person;

‘On whom his enterprise

entirely depended…..[without whom] all his efforts would have been in vain.’[xiii]

The

Justiciar Roger of Salisbury proffered the support of the administration and

handed over the keys to the treasury. Roger of Salisbury wanted the status quo

to continue and Stephen promised this.

|

| Pope Innocent II (L) |

Stephen also

pledged to the Archbishop of Canterbury that he would restore the freedoms of

the church and restoration of all church property lost since 1087, fifty years

previously. This had the beneficial result that, at a council in Oxford[xiv] in April 1136, Stephen was able to

announce that Pope

Innocent II had recognised him as King of England and Duke of Normandy.

Henry of

Blois was an ambitious man who was eager to re-establish the pre-eminence of

the church. In coalition with Roger of Salisbury the pair had the great offices

of the state sewn up, not to mention huge estates and castles. Stephen on the

other hand was being pushed by his barons, to whom he owed much, to not give

way to his brother’s more extreme ambitions.

Bibliography

The Feudal

Kingdom of England 1042-1216 – Frank Barlow, Pearson Education Ltd 1999

Stephen and

Matilda – Jim Bradbury, The History Press 2005

She Wolves –

Helen Castor, Faber and Faber 2010

Early

Medieval England – MT Clanchy, Folio Society 1997

Henry I – C

Warren Hollister, Yale University Press, 2003

The

Plantagenets – Dan Jones, William Collins 2013

King Stephen

– Edmund King, Yale University Press 2010

Doomsday to

Magna Carta – AL Poole, Oxford University Press 1987

At the Edge

of the World – Simon Schama, BBC 2002

Early

Medieval England – Christopher Tyerman, Stackpole Books 1996

Henry II –

WL Warren, Yale University Press 2000

www.wikipedia.en

[ii] Ibid

[iii] At the Palais des Comtes du Maine

[vi]

Failure to hand over the castles before his death was to impede Matilda’s cause

[viii]

Henry I - Hollister

[x]

Richard of Hexham,

Stephen’s chronicler, appears to have got the date wrong in his De Gestis Regis Stephani et de Bello

Standardii

[xi]

King Stephen - King

[xii]

Also known as Henry of Winchester

[xiii]

King Stephen - Henry

[xiv]

Three years later Geoffrey

of Monmouth was to start writing his Historia Regum

Brittanniae in the city