T

he outer

fringes of the Byzantine Empire were now suffering from depredation. There was

insurrection, started by Moorish tribes, spreading across Africa. While the

Ostrogoths were hitting back in Italy and had recaptured Naples. In Persia

Chosroes’ plans for yet another attack on the empire had been stymied by

further bout of the plague and a rebellion fomented by one of his sons. But

this was offset in late summer by the annihilation of a large Byzantine army by

a much smaller Persian force. The army had been marching into Persian held

Armenia.

|

| Assassination of Chosroes |

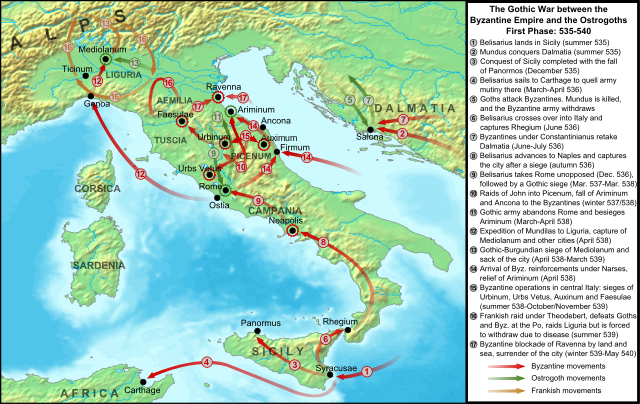

Trouble in Italy

In Italy the

Goths had chosen a new king, Hildebad, but he had not much more than a thousand

fighting men. Five Byzantine generals of secondary abilities were stationed in

Italy, with no one supreme commander. In May 541 Hildebad was beheaded by one

of his guards. His successor tried to come to terms with Justinian and he too

died a violent death.

The new king

now elected was known as Totila and was Hildebad's nephew. Totila was to bring

about a resurgence of Goth fortunes. Totila had been negotiating with the

Byzantines, but when elected to the kingship declared war. Aware that the Goths

were a minority in the country Totila courted the Italian lower and middle

classes. They threw their lot in with Totila and his men in an attempt to throw

off the yoke of empire; having been subject to the rapacity of Justinian’s tax

collectors[i].

Within

months of his accession Totila was able to throw back an imperial army of

twelve thousand men from the gates of Verona and wiped out another in a pitched

battle outside Faventia[ii]. In spring 542 AD the

Goths routed the army of Vitalian’s nephew John, the ablest of the five

Byzantine generals in Italy. Totila’s army now laid siege to Naples.

Totila besieging Florence

Justinian

appointed a Praetorian Prefect who took up residence in Syracuse and refused to

leave the town. Totila defeated a naval expedition sent to relieve Naples and a

second expedition, sent by the prefect in January 543 AD, was destroyed in a

storm. In May the Neapolitans surrendered.

The Byzantine garrison were allowed to leave in peace with all their

possessions and ships were provided to take them to Rome. For the remainder of

the year Totila strengthened his hold on the peninsula.

In January

544 AD the Byzantine generals based in Italy wrote to Justinian informing him

that they could no longer defend Byzantine interests. This letter convinced

Justinian to send Belisaurus back to Italy. Totila addressed an appeal to the

Senate in Rome

‘Surely in these evil days

you must sometimes remember the benefits you were wont to receive, not so very

long ago, at the hands of Theodoric and Amalasuntha…….My Roman friends, only

compare the memory of those rulers with what we now know of the conduct of the

Greeks towards their subjects.’[iii]

John, the

nephew of Vitalian, forbad the Senate to reply and Totila tried a direct appeal

to the Roman populace. The populace, perhaps put off by the military based in

the city, did not rise up. Totila had been busy in the south besieging

Hydruntum[iv]. He left a small force to

continue the siege and marched most of his troops to Rome.

Belisaurus Returns

Belisaurus

was given command of the army in the west, although he had hoped for the

eastern command. Antonina refused to return to somewhere she had been so

grossly insulted and in this she was supported by the empress.

In May 544

AD Belisaurus returned to Italy, not ranked as Magister Militum but as Comes

Stabuli[v]; but Justinian had given

him only inexperienced troops, little authority and no funds. Within a year he

had raised the siege of Hydruntum, and Auximum and rebuilt the walls of Pesaro.

Belisaurus had however seen desertions from his troops, many of whom had not

been paid for over a year. With a population hostile to his forces and all they

represented Belisaurus was facing an uphill task.

In May 545 AD he wrote to Justinian informing

the emperor that he desperately needed men, horses, military equipment and

money. The letter was sent in the hands of John, who dallied in Constantinople

for long enough to woo and marry the emperor’s cousin, thus increasing his

influence in the imperial court. He finally returned bring a large force of

Romans and barbarians under his own command and an Armenian general named

Isaac.

The Fall of Rome

|

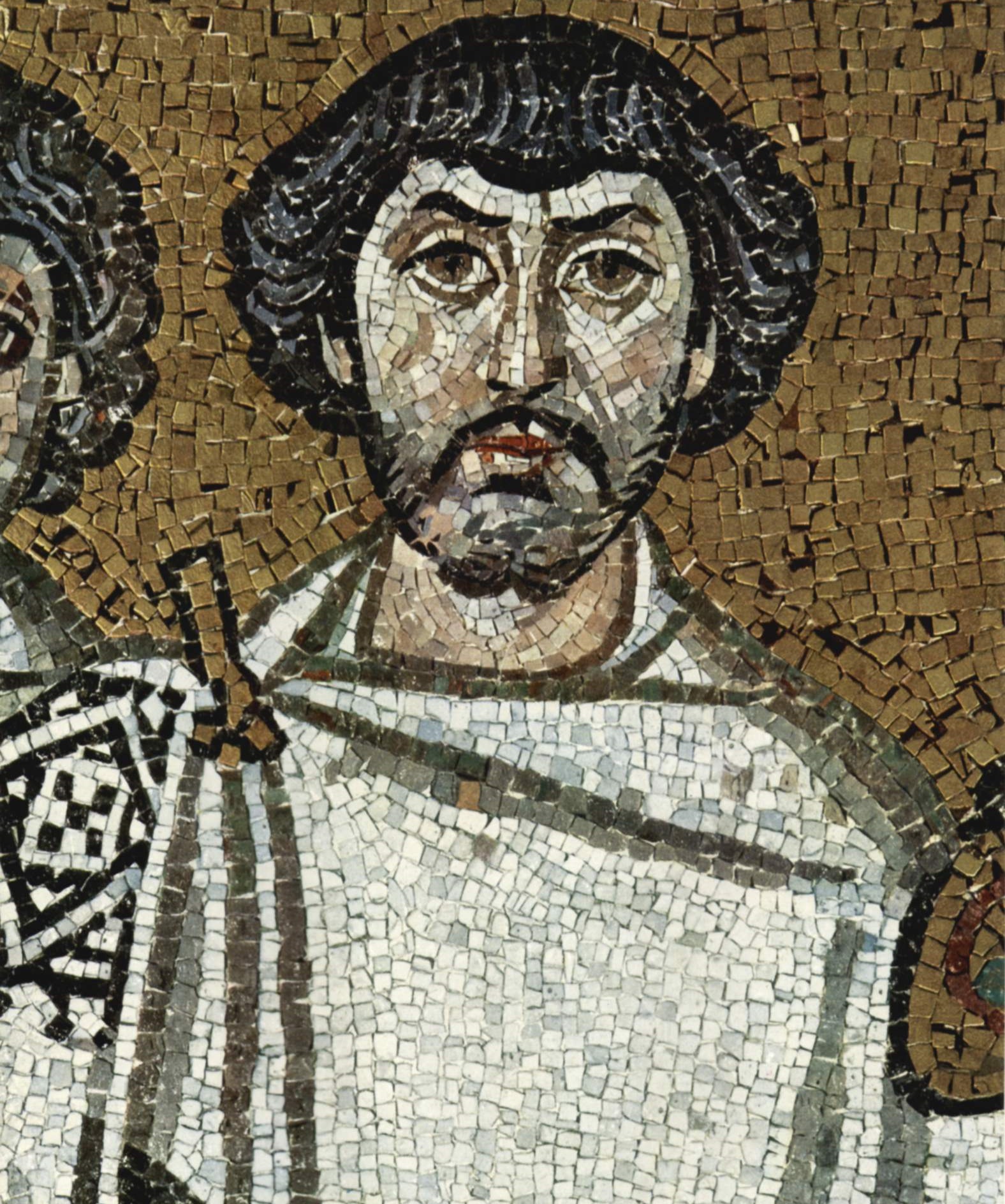

| Totila |

As the new

Byzantine forces landed Totila’s army arrived at the walls of Rome and laid

siege to the city. Bessas, the commander of the garrison was of Goth origin and

his loyalties were uncertain; having failed to lay in emergency supplies[vi]. Totila’s fleet lay at

the mouth of the Tiber. Belisaurus’s relief force broke through the chains laid

across the river. Part of the army had been left in control of Portus, with

supplies, reserves, the last few vessels and most important of all for

Belisaurus, his wife Antonina, under the control of General Isaac.

About to

attack the last major obstacle on the Tiber, before Rome, Belisaurus was

informed that Isaac was dead. Isaac had been informed that he was not to leave

his post under ANY circumstances. Belisaurus assumed that Portus had been taken

and his enemies now had Antonina in their hands. He called off the attack and

returned, only to find that Isaac had disobeyed orders and had attacked Ostia.

Portus and Antonina were safe.

‘Totila was desperate to

catch him outside a protecting wall; but he failed to make contact, as

Belisaurus and the entire Roman army were in the grip of panic fear, with the

result that he not only failed to recover a yard of lost ground but actually

lost Rome as well, and very nearly everything else.’[vii]

This last

chance to relieve Rome was lost as a result of Isaac’s disobedience and

Belisaurus’s uxorious inclinations. In December 546 AD a group of disaffected

soldiers opened the Asinarian gate and the Goths finally retook the city.

Bessas fled with most of the garrison and some nobles. The population took

refuge in the city’s churches.

Totila sent

ambassadors to Justinian suggesting peace.

‘It is our wish that you

should accept for yourself the blessings of peace, and that you should also

grant them to us…….we have excellent examples and reminders in Anastasius and

Theodoric, who ruled not long ago and whose reigns were given over to peace and

prosperity.’[viii]

Justinian

was unwillingly to ‘throw away’ the last ten years of campaigning and the loss

of his cherished ambition to re-unite the two halves of the old Roman Empire.

He claimed that Belisaurus was the person to whom the proposals should be

addressed. Rome was recaptured in April 547 AD and held for three years before

it was lost again.

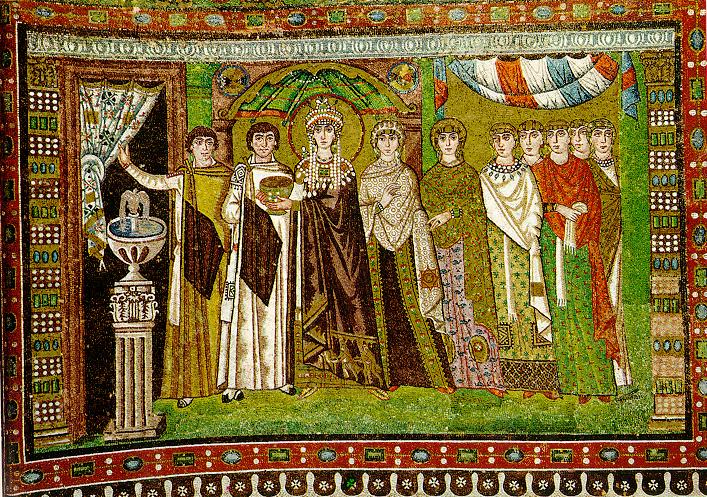

Religious Disputes

Justinian

was now heavily involved in theological matters. The orthodox view of the

identity of Christ had been laid down by the Council of Chalcedon nearly a

century before. In himself Christ united the human and divine. This viewpoint

had never been accepted by the monophysites (of whom Theodora was one) who

believed in only a divine aspect to Christ.

The

monophysites were to be found in the eastern Mediterranean and were too

numerous to be eliminated. Egypt, the empire’s source of grain, was a centre

for the monophysites and harsh treatment could incite a rebellion. Treating

them too well ran the risk of upsetting the orthodox. For years Justinian had

been outwardly rigid, but his hard line was tempered by Theodora, who had

maintained a discreet monastery in the Great Palace.

Now a

charismatic new leader, Jacob Baradeus, was championing the monophysite cause.

He was consecrated Bishop of Edessa in 543 AD, by the exiled Patriarch of

Alexandria; although unable to take up his see Jacob embarked on a mission to

revive monophysitism. He travelled through Syria, Palestine, Mesopotamia and

Asia Minor consecrating thirty bishops in his travels and ordaining several

thousand priests.

Justinian

was already being criticised for his ‘hands-off’ policy towards the

monophysites, yet their newly awakened fanaticism required careful handling if

rebellion against the empire was not to ensue. He chose instead to chastise the

Nestorians, an obscure sect who proclaimed the humanity of Christ rather than

his divinity. Very few remained in the empire, most had fled to Persia; the

paucity of Nestorians in the empire meant that action against them would not

cause the crises that attacking the monophysites might. The Nestorians had the

additional attraction of being hated by Orthodox and monophysites alike.

The

anti-Nestorian edict in 544 AD pleased very few; the orthodox toed the

emperor’s line, somewhat unwillingly. The monophysites were unappeased, having

expected concessions from Justinian, while the Roman clergy were livid with

anger. Justinian had condemned writings accepted by the Council of Chalcedon

and the papal legate in Constantinople pronounced a ban on the Patriarch.

Justinian had offended the Roman church at a problematic time in Italy for the

empire.

In the

autumn of 545, as Totila’s army surrounded Rome, a company of excubitors seized

Pope Vigilius and carried him off down river. He was taken to Catania in

Sicily, where he stayed for a year, not arriving in Constantinople until

January 547 AD. He still stood firm in refusing to condemn the works disparaged

in Justinian’s edict of 544 AD. Vigilius was given a palace of his own, but

even so placed the patriarch and all bishops, who had subscribed to the edict,

under several months excommunication.

Pressure

from Theodora and Justinian resulted in a show of reconciliation between

Vigilius and the Patriarch Mennas on 29th June. The Pope also handed

Justinian his signed condemnation of the chapters referred to in the edict. The

condemnation was not published until April 548 AD.

Eleven weeks

later Theodora was dead. After her death many of her former protégés repudiated

statements made during her lifetime, supporting the edicts. Vigilius’ actions

had weakened the authority of the Council of Chalcedon and he was reviled as a

turncoat; some African bishops excommunicated him.

Bibliography

Byzantium –

The Early Centuries – John Julius Norwich, Folio Society 2003

The Secret

History – Procopius – Folio Society 1990

En.wikipedia.org

[i] The tax collectors were given one twelfth of all they collected.