|

| Andrew's Assassination |

The Assassination

On 18th

September Andrew was murdered at Aversa, possibly on Catherine’s order. He was

preparing for bed[i]

when he was informed that a courier had arrived with important paperwork for

him. The report sent to Avignon was quite clear;

‘He went into the

gallery…..Certain ones placed their hands over his mouth, so that he could not

cry out, and in this act they so pressed the iron gauntlets that their print

and character were manifest after death. , others placed a rope around his

neck, in order to strangle him, and this likewise left its mark.’[ii]

Andrew was

suspended over the balcony of his room and the rope holding him was cut. The

sound of Andrew’s body hitting the ground woke his nurse Isabelle. She rushed

in to discover the assailants who hurriedly dispersed at the sound of her

screams. There is a possibility that Joanna was complicit in his death. King

Louis was incandescent with rage at his brother’s murder.

Isabelle

sent her son Nicholas to report to Louis and Elizabeth on Andrew’s death. the

newsmongers of the day now had a story they could sensationalise and Giovanni

Villani had a cracker given to him direct by Nicholas;

‘When morning came, the

entire population of Aversa went to the Queen’s residence to find out who had

perpetrated such a crime, and to exact retribution. The queen suddenly blushed,

and, as if transfixed, kept her head down and her tearless eyes averted.’[iii]

Villani’s

report had Joanna fleeing Aversa leaving Andrew’s body to the elements; the

truth of course is very different; Andrew was buried on the 20th in

the cathedral at Naples.

The same day

one of the assailants was apprehended; Tomaso Mambriccio, one of Andrew’s

personal servants, who had been paid for his involvement in the crime. Andrew

had threatened to execute Tomaso once Andrew had been crowned. Although Tomaso

had been tortured before his death, his torturers had carefully removed his

tongue to ensure that he could not implicate his fellow conspirators, including

the person who had paid Tomaso, who was executed.

The Aftermath

|

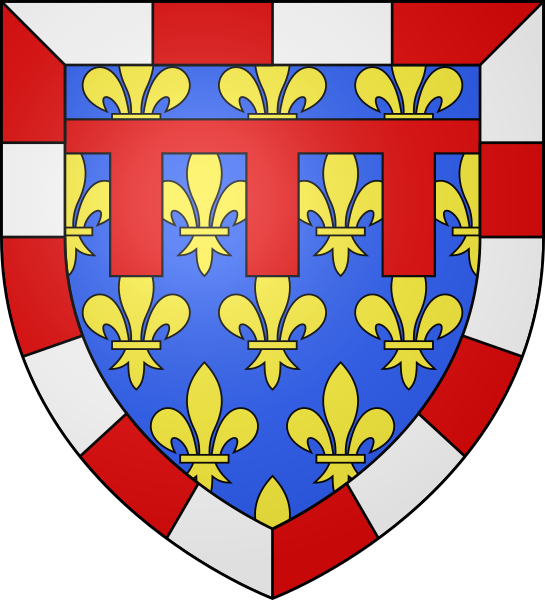

| Joanna's seal |

Both Joanna

and Charles of Durazzo contacted the Hungarian court, seeking their support.

Charles hoped to turn the death of Louis’ brother to his advantage, whilst

Joanna was desperately hoping to placate the Hungarians. She also sent

despatches far and wide attempting to spin the news of Andrew’s murder,

informing the city of Florence[iv] that the principal

assassin had been put to death.

Clement’s

letter in reply warned Joanna;

‘Be sedulously on your guard

as to whom you trust, and whom you ought to avoid.’[v]

One of the

people Joanna needed to guard against was Clement himself who hurriedly wrote

to Louis, failing to mention his ambivalence towards Andrew and his many

changes of policy and the vexed question of Andrew as ruler of Naples. Clement

did not want further strife in Europe; he was already concerned about Edward

III’s posturing in the west. To forestall Louis’ complaints, Clement decided to

send two cardinals to investigate Andrew’s death.

War Comes To Naples

On 25th

December 1345 Joanna gave birth to her son Charles Martel. She placed Charles Martel in the

hands of Andrew’s nurse Isabelle, possibly as a sop to Andrew’s relatives, and

convinced Clement to stand as his godfather. Joanna’s emissary to Hungary was

charged with negotiating Joanna’s release from the nuptial treaty of 1333 to

leave her free to remarry.

Louis was

furious and wrote to Clement alleging that Joanna was his brother’s murderer.

Clement’s emissaries had been dilatory and had not yet arrived in Naples to

even begin their investigations. His mother Elizabeth demanded that Clement

remove Joanna as queen of Naples and crown her third son Stephen king in Joanna’s place. Charles

Martel was to be sent to his grandmother in Hungary.

Joanna

determined to marry her cousin Louis of Taranto. She was in need of a husband who understood the

political undercurrents in her kingdom. As well as being family Louis was tall,

blond and handsome and a tested warrior. Louis’ brother had already forced

Joanna to agree to wed him and now Naples was rent by a war between the two

brothers.

Robert of

Taranto allied with Charles of Durazzo and the two men used their own retainers

to form the nucleus of an army; whilst Louis was forced to recruit a mercenary

army from outside the kingdom, with the assistance of his mother’s lover

Niccolo Acciaiuoili. Robert and Charles, along with the rest of the Durazzo

brothers, claimed they were fighting to bring Andrew’s murderers, who were

allegedly being harboured by Joanna and Louis, to justice. Clement wrote of

Louis;

‘If his marriage is

accomplished, those who are vulnerable for being suspected of participating in

the criminally infamous death of the king are guaranteed by Louis to be

declared safe from punishment.’[vi]

Hugo del

Balzo switched sides and became a secret emissary of the pope’s. The dilatory

behaviour of Clement’s cardinals rebounded, unfairly, on Joanna. The citizens

of Naples objected to the foreign army and protested against Joanna’s

protection of Andrew’s murderers. Philippa’s son Raymond, as seneschal of the

court, ordered that arms were not to be carried in public and he and his men

attempted to enforce his order.

The Nightmare

_(15397707910).jpg/800px-Castel_dell'Ovo_(1)_(15397707910).jpg) |

| Castel dell'Ovo |

Unfortunately

Raymond was captured and was tortured in front of a mob. His tongue was cut out;

even so Charles and Robert managed to extract a long list of Raymond’s

associates despite this obvious drawback. Raymond implicated himself as well as

his mother and many more of Joanna’s associates.

Charles and

Robert urged the mob to attack Castel Nuovo. Joanna had moved to Castel dell’Ovo, the most secure fortress in Naples. It was decided to

besiege the Caste Nuovo and wait for their supplies to run out, which took

three days. Huge del Balzo helped broker the negotiations between the terrified

courtiers and the avenging duo.

The

prisoners were to be transferred to the Castel dell’Ovo for safekeeping until

the Neapolitan chief justice could investigate the claims against them. Hugo

del Balzo offered to transfer the captives by sea, an offer which was accepted.

Instead, once the accused were on board Hugo had his ship moored in the middle

of the bay where he set to with a vengeance;

‘In front of the whole city

and upon the open sea – he naturally tortured poor Philippa, Sancia [her

daughter][vii]

and Robert[viii]

upon a monstrous rack.’[ix]

Having

broken the agreement with a vengeance, Hugo then turned over his captives to

Charles of Durazzo who further tortured the prisoners. The prisoners were

finally moved to Castel Capuano. Louis was forced to retreat to

Capua while his brother took control of Naples. Louis’ army was ordered to

leave the kingdom and citizens were forbidden to aid him.

Civil War

|

| Benevento |

A war of

moves and countermoves now commenced. Robert of Taranto urged Clement to issue

the dispensation necessary to allow him to wed Joanna, while Joanna wrote to

Clement informing him of her determination never to wed Robert. On 24th

April Robert named himself Captain General of the kingdom; in a counter move on

30th April Joanna assigned control of a large battalion of troops to

Louis. On May 6th Robert took control of all public finances; on 30th

Joanna assigned Louis six thousand ounces of gold.

Despite the maleficent

attentions of his brother, Louis was able to put together an army and upon

reaching Benevento the city surrendered to him. By June

his forces were sited on a hill overlooking Naples. There he waited and

marshalled his forces. But in the north King Louis was preparing to make his

move.

Following an

impassioned letter to Clement from the dowager queen of Hungary demanding that

Maria be divorced from Charles of Durazzo and that Joanna never be allowed to

marry again, Clement informed Elizabeth that her son’s murderers would be

brought to justice, but that if Hungary invaded Naples it would be regarded as

an enemy of the church.

|

| Castel Dell'Ovo from the sea |

Clement

authorised Bertrand del Balzo, the Neapolitan Chief Justice[x], to investigate Andrews

murder. At the same time he informed Bertrand that any member of the royal

family implicated in the assassination was to be referred to the jurisdiction

of the pope.

Bertrand had

several of the prisoners, who had been tricked into his cousin’s tender care,

tortured and when they confessed had them executed, after stripping them of

their titles and lands.

‘The prisoners

were…..paraded through every street in Naples, flagellated repeatedly, their

flesh mercilessly seared by the torturer’s hot irons….they were spat upon and

stoned. When at length they arrived [at the bonfire]……Master Robert had already

just passed away.’[xi]

Bertrand

took one of Sancia’s Provencal estates for himself[xii].

Bibliography

The Holy

Roman Empire – Friedrich Heer, Phoenix 1995

Joanna –

Nancy Goldstone, Phoenix 2010

Absolute

Monarchs – John Julius Norwich, Random House 2011

A Distant

Mirror – Barbara Tuchman, MacMillan London Ltd 1989

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

He and Joanna had separate bedrooms

[ii]

Joanna - Goldstone

[iii]

Joanna - Goldstone

[iv]

The kingdom’s principal trading partner

[v]

Joanna - Goldstone

[vi]

Ibid

[vii]

Sancia was pregnant and her mother was in her

sixties

[viii]

Robert of Cabannis, another of Sancia’s sons

[ix] Joanna – Goldstone

[x]

And cousin of Hugo del Balzo

[xi]

Joanna - Goldstone

[xii]

Sancia and Philippa were not executed until

later, but their estates were confiscated too

.JPG/450px-Porta_San_Giovanni_(Aversa).JPG)