Thomas Becket – Man or

Saint? Henry II – King or Sinner?

Thomas

Becket was born in circa 1118 of a middle-class Norman family. Becket was the

son of a merchant who served a term as sheriff of London. Thomas was educated

at Merton Priory, and later attended school in London and studied for a while

in Paris. After schooling Thomas worked as a clerk and accountant for the

sheriff’s office. At some point in his youth Becket made a vow of chastity. He

joined the household of Archbishop Theobald. Formerly Abbot of Bec, Theobald

had been appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by King Stephen in December 1138.

Stephen had

been in conflict with his cousin Matilda (also known as Maude) since the death

of Matilda’s father Henry 1 in December 1135. Both had claimed the crown and

the country was divided in a civil war that lasted until 1153. The period was

described at the time as a period ‘when Christ and his saints slept’

Matilda’s

son Henry had taken up the reins of the fight from Matilda in 1149 at the age

of 16. His father Geoffrey of Anjou was by that time already de facto Duke of

Normandy, but had offered to hand the dukedom over to his son as soon as he was

old enough to take over the responsibility inherent in ruling. At some point

between November 1149 and March 1150 Geoffrey made good on his word and Henry Plantagenet

was made Duke of Normandy. The King of France, who had only just returned from

a crusade, was not prepared to confirm Henry in his dukedom, especially as

there was the prospect of his being made King of England.

Geoffrey

advised his son to part with the lands known as the Vexin to assure royal

recognition of his dukedom. Peace was made in Paris in August 1151. Henry paid

homage to King Louis and was invested as Duke of Normandy. On 7th

September Geoffrey, Count of Anjou died suddenly and Henry had to journey to

Anjou to be invested as its count.

Henry’s Marriage

|

| Eleanor's marriage to Louis |

On 18th

May 1152 Henry, Duke of Normandy, married Eleanor of Aquitaine, daughter and

heiress of the Duke of Aquitaine and former Queen of France. They were married

eight weeks after a council of French clergy had agreed with King Louis’ wishes

to be parted from his wife. Louis had loved his wife, although they were two

very different characters – she was outgoing and enjoyed flirtations while

Louis as ascetic. The marriage had produced two daughters and Louis needed a

son to inherit his throne. It is believed that this was the reason for the

divorce.

Henry was

eleven years Eleanor’s junior but was the most eligible of those wanting to marry

this exceptionally rich heiress, whose vast estates (nearly half of France)

were not directly controlled by the French crown. Eleanor avoided being waylaid

by the Count of Blois and an ambush by Henry’s younger brother Geoffrey on her

journey to Poitou where she married Henry

His Grandfather’s Heir

It was not

until November 1153 that Stephen finally met with the son of his adversary at

Winchester, in an attempt to resolve the question of inheritance of the throne

of England. Stephen's elder son Eustace had already died suddenly earlier int he year. Now Stephen agreed to make Henry his heir, dispossessing his son

William. Henry agreed to allow Stephen to reign for the remainder of his life,

providing that the king, bishops and other magnates would swear to allow Henry

to become king without denial after Stephen’s death. Henry also agreed to allow

William all the honours his father had bestowed upon him.

Stephen died

on 25th October 1154 and on 7th December Henry and his

wife Eleanor of Aquitaine set sail from Barfleur. Theobald crowned the couple

king and queen of England at Westminster Abbey on 19th December.

Henry was twenty-one, the first of the Angevin monarchs of England.

England’s Chancellor

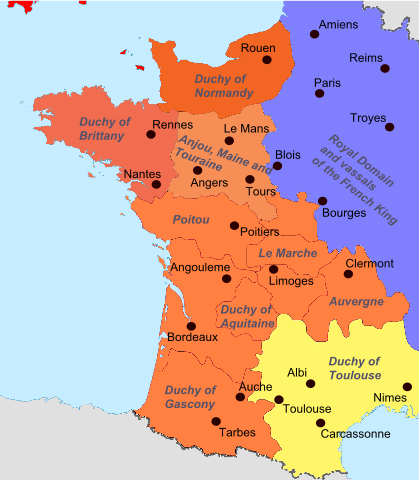

|

| Full extent of Angevin Empire |

Theobald

entrusted Thomas Becket with several missions to Rome and sent him to Bologna

and Auxerre to study canon law. In 1154 Becket was made Archdeacon of

Canterbury and given several benefices. In 1155 Theobald recommended Becket to Henry

as Lord Chancellor. Henry had already appointed one of Stephen’s men as head of

the administration – Richard de Lucy and created one of his own supporters, Robert

de Beaumont, his co-justiciar. Robert had been energetic in attempting to bring

both sides of the civil war together, but his support was given to Duke Henry.

Henry accepted Theobald’s recommendation, giving him Theobald’s support and

that of the English church.

As

Chancellor Thomas was much in the company of Henry and the two men became

friends, as much as any man could with the peripatetic king, whose realms

stretched from the far north of England to the Pyrenees. He was the companion

of a young and relatively inexperienced king. But even as a young man Henry was

able to extract deference from those around him. Barons and bishops bowed down

before Henry’s wrath and or intransigence.

Becket’s

chancellorship was partly notable for the state that he kept, displaying an

eagerness for marks of status and the privileges of rank. Henry’s tastes were

far simpler and his household was far less impressive. On a visit to France in

1157 Becket travelled with a great entourage, while the king’s visit was on a

far smaller scale. Becket had the king’s confidence and was entrusted with

matters above and beyond those normally given to a chancellor.

Archbishop of Canterbury

Theobald

died on 18th April 1161 and Henry pressed the suit of his friend

Thomas as candidate to the Archbishopric. An unsuccessful campaign in Toulouse

had led to a waning of Thomas’ influence on Henry. Henry was apparently warned

against the appointment, including by Thomas himself who said that the

appointment could lead to a breach in their friendship.

But Henry

was loyal to his friends and hoped to have some influence on church affairs

through his friendship with Thomas. However Thomas as Archbishop seemed to go

out of his way to insult the king, never a sensible option with a man of Henry’s

temper. Rather than follow his predecessor’s more subtle approach Thomas may

have been trying to impress his new subordinates, to prove that he was his own

man, rather than the king’s.

When he

received the Pope’s approval to his appointment Thomas resigned as Chancellor,

much to Henry’s surprise. The joining of two posts was not unusual and the

emperor of Germany had an archbishop as chancellor. Thomas claimed that he

could not manage the two roles. Thomas was also provocative in other matters,

demanding homage from one of Henry’s barons for a castle within the

jurisdiction of Canterbury. If the case had been taken to the royal court he

may have been successful, but his strategy merely inflamed the Angevin temper.

Criminous Clerks

Henry was

set on reforming the English legal system and it is for this work that his

reputation should be based on, rather than for the unfortunate events that

followed his quarrel with Thomas. The introduction of the system of trial by jury

was Henry’s triumph. The anomalous position of members of the clergy who

committed crimes was an issue that Henry wanted resolved.

As many as

one on six of the population were clerks in minor orders, most of whom would

never be ordained as priests. But they all claimed the privilege of clergy; to

be tried by the religious rather than secular authorities for any crimes. As a

result ‘clerks’ were getting away with rape, murder and worse courtesy of the

church. Henry wanted to ensure that criminous clerks were brought to justice. Becket

wanted the church to retain secular immunity for crimes committed.

Early in his

reign Henry had allowed Theobald to try and punish an Archdeacon accused of

poisoning his Archbishop. This was an action Henry no doubt now regretted. It was

however a precedent for Thomas to use. Notorious abuses of the clerical courts

were brought to the king’s attention and there can be little doubt that the secular

officials, irritated by the over 100 murders by clerks reported to the king

along with numerous cases of theft and robbery with violence, were supportive

of a change to the law.

Thomas did

realise that some cases were too flagrant breaches of law and did try to impose

harsher sentences, but in doing so he encroached upon the royal prerogative.

Bibliography

Henry II –

WL Warren, Yale University Press 2000

Eleanor of

Aquitaine – Alison Weir, Jonathan Cape 1999

http://en.wikipedia.org

An unnecessarily irritating man, Thomas....

ReplyDelete