|

| The Battle of Lowestoft |

Fighting on the High Seas

Rupert fell

ill with complications to the head wound he had received in fighting during the

Thirty Years’ War. He did not recover to take part in active duty until late

1664 when he accompanied James on an inspection of the fleet. The inexperienced

James was overcome with the might of the English fleet and acquiesced when

Parliament pressed Charles to declare war on the Dutch and voting £2.5 million[i] to prosecute the 2nd Anglo-Dutch War[ii].

The most

important causus belli was trade; the

English were treading on the tails of the Dutch in America, Africa and the East Indies. Rupert was Vice-Admiral of the fleet and Admiral of the

Second Squadron under James’ leadership. James strategy was to blockade the

enemy ports until the Dutch fleets were forced to make a dash for the open

seas, to defend their trade routes.

The Battle of Lowestoft on 7th June 1665 was a victory for the

English sinking 20 Dutch warships and with four enemy admirals dead. But due to

an untimely intervention by Henry Brouncker[iii] the Dutch fleet escaped. Rupert

later reported to parliament;

‘I shall only say, in short,

if the Duke’s orders, as they ought, had been strictly observed, the victory

which was then obtained had been much greater, nay, in all probability the

whole fleet of the enemy had been destroyed.’[iv]

|

| Sir Robert Holmes (R) with Sir Frescheville Holles |

During the

battle Rupert’s Rear Admiral, Robert Sansum died; to replace him Rupert nominated

his friend Robert Holmes. James preferred his own man John Harman[v].

‘The Duke went aboard the

Royal James to see Prince Rupert, who kept to his chamber of a sore

leg......but his Royal Highness thought more fit to give that flag to Capt.

Harman.’[vi]

Rupert’s man

Holmes then resigned his commission; he was however well able to support

himself with the civil and military appointments already gifted to him[vii].

Henrietta

Maria was horrified by the English losses during the fighting and persuaded

Charles that it was not suitable for the heir to the throne to put himself in

harm’s way. Accordingly James was confined to shore. Charles offered a joint

command to Rupert and the Earl of Sandwich, one of Rupert’s old adversaries.

Rupert felt that a divided command was worse than useless and declined.

Sandwich was put in overall control but was soon found guilty of taking bounty

from Dutch merchantmen and sent off to Spain as the English ambassador.

The Four Days Battle

|

| the Four Days' Battle |

In early

1666 command of the navy was divided between George Monck[viii] and Rupert. The country

now faced the prospect of fighting not only the Dutch but also France; Louis

XIV had decided to oppose his cousin’s expansionist policies. The Netherlands

and France were joined by Denmark

in the war against the English.

Monck and

Rupert set about tightening discipline and demanded adequate and appropriate

ammunition for the fleet, now down to 66 ships[ix]. James ordered that the

fleet be divided between the two commanders. So when the French, under the Duke of Beaufort, left Toulon, Rupert sailed to

intercept him and Monck was left on his own to attack the Dutch.

The Four Day’s Battle begun twenty miles off Ostend. On 1st June Monck and his men were caught between two lines

of fire; the following day, reduced to 40 ships Monck attempted to sail back to

the English coast. He was joined by Rupert and his fleet on the afternoon of 3rd

June and the two admirals agreed to attack the following day. Pepys records

that Monck[x];

‘By and by spied the

Prince’s fleet coming......the Prince came up with the Generall’s[xi]

fleet, and the Dutch came together again and bore towards their own coast.’[xii]

The End of a Tumultuous Year

|

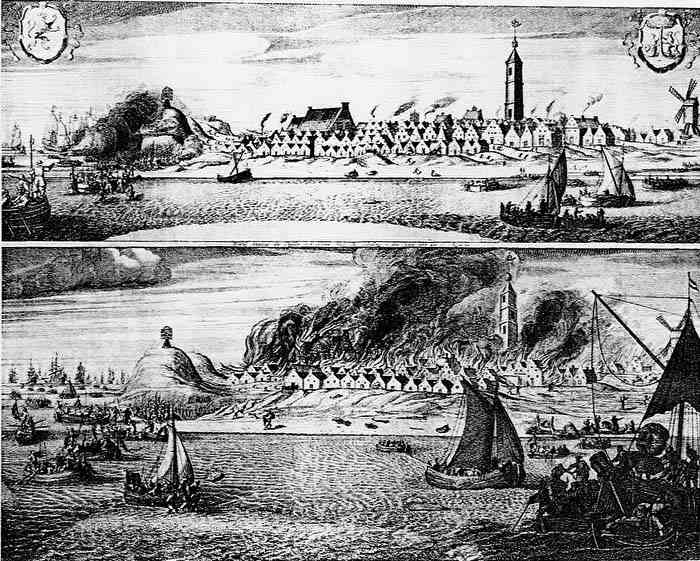

| Holmes' Bonfire |

A further battle took place on 24th July

off Orford Ness, victory going to the English by a

narrow margin. On 9th August Robert Holmes, back with the navy, raided the islands

of Vlieland and Terschelling, off the Zuider Zee. He claimed to have burnt 150 merchantmen at anchor on the

islands, costing the Dutch £1 million[xiii].

In early

September Monck was diverted back to London to help deal with the consequences

of the Great Fire in London.

Rupert

prepared a detailed report on the campaigning season, blaming poor intelligence

about the intentions of the French fleet, the intentions of the Dutch and

finally the whereabouts of Monck when Rupert’s fleet was ordered to join them

to give battle. Rupert referred to ‘intolerable

neglect’ in provisioning and maintenance of the ships. He also recommended

that Harwich’s defences should be upgraded along

with those of Sheerness. The Duke of York’s decision to ignore

this advice was to cost the country dear.

%2C_Duchess_of_Cleveland_by_Sir_Peter_Lely.jpg/487px-Barbara_Palmer_(n%C3%A9e_Villiers)%2C_Duchess_of_Cleveland_by_Sir_Peter_Lely.jpg) |

| Barbara, Lady Castlemaine |

Pepys and

the Navy Board retaliated to Rupert’s complaints by asserting that Rupert

brought the fleet home in bad condition at the end of the fighting season. At a

meeting on 7th October Rupert informed a meeting that;

‘Whatever the gentleman

[Pepys] said, he had brought home his fleet in as good a condition as any fleet

was ever brought home.’[xiv]

Pepys and

the Navy Board were at cross purposes with Rupert. The navy was suffering from

underfunding; Pepys had asked for £100,000[xv] to keep the fleet afloat,

he was given £5,000[xvi] by Charles who was far

happier to lavish money on his mistresses, especially the voracious Lady Castlemaine who held the king in thrall.

Difficult Decisions

|

| Trepanning |

During the

winter Rupert underwent two trepanning operations on his head to alleviate the problems caused by

his head wound. The second was to alleviate many of the problems caused by the

botched first operation. Rupert was having problems sleeping and the constant pain

in his head was worsening. Rupert believed that he would die, but Pepys wrote;

‘Since we told him that we

believe he would overcome his disease, he is as merry and swears and laughs and

curses, and do all the things of a man in health, as ever he did in his life.’[xvii]

Pepys

believed that Rupert’s illness was a result of the clap[xviii] having gone to

Rupert’s head.

News of

Rupert’s death were rumoured on the Royal Exchange on 16th February, but

Pepys was able to rectify the stories. Rupert used his convalescence to create

refined versions of the surgeon’s tools used in his operation.

The Earl of

Clarendon and his cronies were now responsible for the fatal decision to lay off

sailors and lay up the larger warships; made because they believed the war

almost won When he heard of the decision and was off his sickbed Rupert

protested to Charles.

Difficult Times

|

| Battle of the Medway |

Early in

June 1667 de Ruyter’s men captured Sheerness. The majority of the Dutch fleet

remained off Sheerness but a force under Willem van Ghent attacked the Chatham navy yards in the Battle of the Medway. Van Ghent fired six warships and sailed off with

James’ flagship, the Royal Charles and the Unity; a PR disaster for both Charles and the Navy Board. Pepys

wrote;

‘Our hearts do now ake; for

the news is true, that the Dutch have broken the Chain[xix]

and burned our ships, and particularly the Royal

Charles; other perticulars I know not, but most sad to be sure.’[xx]

|

| Upnor Castle |

Rupert was called

upon to assist James and Monck as they summonsed troops to Upnor Castle[xxi]. Rupert deployed a battery of

artillery at Woolwich, where he knew the enemy would have

to pass. Lord Arlington[xxii] wrote;

‘On Thursday they came on

again with 6 men of war and 5 fire ships.....but were so warmly received by

Upper (sic) Castle and battery on the shore that they were forced to retire,

with great damage beside the burning of their 5 fire ships.’[xxiii]

The Dutch

were at point blank range when Rupert, in his element, gave the first order to

fire. The Dutch retired to the mouth of the Thames and maintained control of

the Channel for the next few weeks.

In December

1667 Pepys proposed that any officer wishing to be made a lieutenant should

have served in the navy for three years, have a certificate from his captain

and passed an exam in navigation and seamanship at the Navy Office. Rupert

opposed this radical change, but the flag officers and Charles approved.

Bibliography

Prince

Rupert of the Rhine – Maurice Ashley, Purnell Book Services Ltd 1976

Samuel

Pepys, the Man in the Making – Arthur Bryant, Collins Clear Type Press 1948

The Later

Stuarts – George Clark, Oxford University Press 1985

Charles II –

Christopher Falkus, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1972

The Shorter

Pepys – Robert Latham (ed), Penguin Books 1987

Prince

Rupert of the Rhine – Patrick Morrah, Constable & Company 1976

Man of War –

Richard Ollard, Phoenix Press 2001

Prince

Rupert – Charles Spencer, Phoenix Paperback 2008

Samuel Pepys

– Claire Tomalin, Alfred A Knopf 2002

[i]

In 2014

the relative: historic opportunity cost

of that project is £340,100,000.00 economic cost of that

project is £77,830,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[ii]

The 1st

Anglo-Dutch War occurring during the Commonwealth, ending in August 1653

after the death of Admiral Tromp at the Battle of Scheveningen

[iii]

One of James’ courtiers

[iv]

Prince Rupert - Spencer

[v]

Later Admiral

[vi]

Man of War - Ollard

[vii]

Deputy Governor of the Isle of Wight, Governor of Sandown Fort and Captain of

his own Independent Company of Foot

[viii]

Now Duke of Albemarle

[ix]

The previous year’s plague had killed off many sailors

[x]

Pepys’ patron; Pepys had a low opinion of Rupert

[xi]

De Ruyter

[xii]

The Shorter Pepys - Latham

[xiii]

In 2014

the relative: historic standard of living

value of that income or wealth is £150,700,000.00 economic status value of that income or wealth is £4,208,000,000.00 economic power value of that income or wealth is £28,600,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[xiv]

Rupert of the Rhine - Ashley

[xv]

In 2014

the relative: historic opportunity cost

of that project is £14,110,000.00 economic cost of that

project is £2,860,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[xvi]

In 2014

the relative: historic opportunity cost

of that project is £705,700.00 economic cost of that

project is £143,000,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[xvii]

Prince Rupert - Spencer

[xix]

Across the channel of the Medway

[xx]

The Shorter Pepys - Latham

[xxi]

An Elizabethan fort outside the Chatham dockyards

[xxii]

An ally of Barbara Castlemaine’s against Clarendon; Arlington was one of those

charged with management of the war

[xxiii]

Prince Rupert - Spencer

heh, I never knew Lowestoft and Orford had such excitement. The changes to the regulations for a lieutenant set the basis for the later Royal Navy of Nelson.

ReplyDelete