|

| York Minster |

Chancellor of England

Although

Bishop of Lincoln Geoffrey was still in minor orders and had not been

consecrated. Losing patience Pope Alexander decided that the current situation

could not continue and in 1181 he wrote to Henry demanding that Geoffrey be

consecrated straight away or made to resign. Geoffrey was not prepared to take

this step that would lock him into the church and wrote asking for a further

three years. Alexander refused.

Geoffrey and

Henry came to an agreement; if Geoffrey resigned his see his father would make

him Chancellor of England and be granted lands and office to

offset his lost clerical revenues. Geoffrey was granted the archdeaconry of

Rouen, the post of treasurer of York Cathedral and two castles in Anjou, giving him an income of £650 per annum[i].

Geoffrey

resigned the see of Lincoln on 6th January 1182. Geoffrey

was to remain Chancellor for the rest of his father’s reign, but his father’s

prodigious energy was failing; what was to follow was a long period of decline.

Rebellious Offspring

.jpg/640px-BnF_ms._12473_fol._160_-_Bertran_de_Born_(1).jpg) |

| Bertan de Born |

Henry was increasingly isolated by his legitimate children’s lust for

power. Henry the Young King was determined to inherit all his father’s lands;

on the other hand Richard was determined to have Aquitaine. He refused to pay

homage to his elder brother, arguing that they were equals. Richard decided to

strengthen his borders and built a castle at Clairvaux. Bertran de Born, a

minstrel, wrote a chanson;

‘Someone

has dared to build a fair castle at Clairvaux, in the midst of the plain.

I

should not wish the Young King to know about it or see it,

for

he would not find it to his liking;

.jpg) |

| The Young King |

Henry the Younger alleged that the new chateau encroached on territories

bound to Anjou. In February 1183 open

warfare broke out; Henry the Younger left for Aquitaine, ostensibly as a

mediator between Richard and his father. But when Henry travelled to Limoges he was

met by flights of arrows, one of which pierced his cloak. Henry the Younger,

along with Count

Aymer and other discontented rebels, claimed

the assault was a misunderstanding.

Henry the Younger was supported by his brother Geoffrey of Brittany who

organised a wholesale invasion of Poitou. The

French king Philip[iv] sent

assistance to the rebels, joining brigands provided by Aymer.

Henry was concerned that a general uprising would ensue and ordered the

arrest of any of his nobles in England likely to join his sons. Henry’s fears

were unfounded; none of his barons in England rose up and nor did Aquitaine,

although the county dissolved into general disorder.

Henry the Younger left Limoges to attack some of Richard’s more

vulnerable castles, after plundering the townsfolk and the shrine of St Martial of their

wealth to pay his mercenaries. Failing in his mission Henry the Younger

returned to Limoges where he was greeted with a hail of rocks. He retreated,

picked up dysentery and died at Martel on 11th

June 1183. He was buried at Rouen. Without the Young King the revolt faded

away; his supporters

‘Made

haste to go about their own business.’[v]

France Intervenes

|

| Geoffrey of Brittany |

Henry tried to play his children off one against the other, but Philip put

his oar in, continuing to play Henry’s children off against their father. In

1186 Geoffrey of Brittany died after being unhorsed and trampled underfoot in a

tourney in Paris on 9th June; he succumbed to the resultant fever.

Geoffrey appears to have been plotting with Philip. He left behind a pregnant

wife. His posthumous son Arthur of Brittany[vi] was to be his heir. Geoffrey was

buried in Notre Dame;

‘With

but few regrets from his father, to whom he had been an unfaithful son, but

with sore grief to the French.’[vii]

King Philip apparently had to be restrained from throwing himself into

the grave. Instead he started working on the new heir apparent’s discontent. He

was fortunate in that Richard had built up a huge backlog of discontent with

the aid of his mother, whose darling he was.

Philip now demanded that Henry allow Richard to marry Alys[viii], Countess

of the Vexin. Alys, Philip’s half-sister, had been living in the English court

for twenty-five years[ix]. Richard had not pressed

for the marriage to take place. Rumour claimed that Henry had seduced Alys and

Richard seems to have believed the stories[x].

|

| Chateau de Gisors |

In 1187 the vexed question of the Vexin arose once again; Philip ordered

the building of a castle at Gisors, close to

Henry’s stronghold on the

border. Henry’s men rode out to stop the building and in the ensuing fight

killed the son of one of Philip’s sworn men. Two conferences held in the spring

kept the peace for a short while, but in the summer Philip invaded Berry. War

looked imminent but the papal legates intervened to stop the battle both sides

were preparing for.

Richard was persuaded to return to Paris with Philip and Richard offered

allegiance to Philip for all his father’s lands across the seas. The two men

became close;

‘Every

day they ate at the same table and from the same dish, and at night had not

separate chambers.[xi]’[xii]

Philip was not as successful at separating Richard from his father as he

had been with Geoffrey. Richard was intent on holding Aquitaine against all

comers and was rightly suspicious of Philip’s motives.

Death of a King

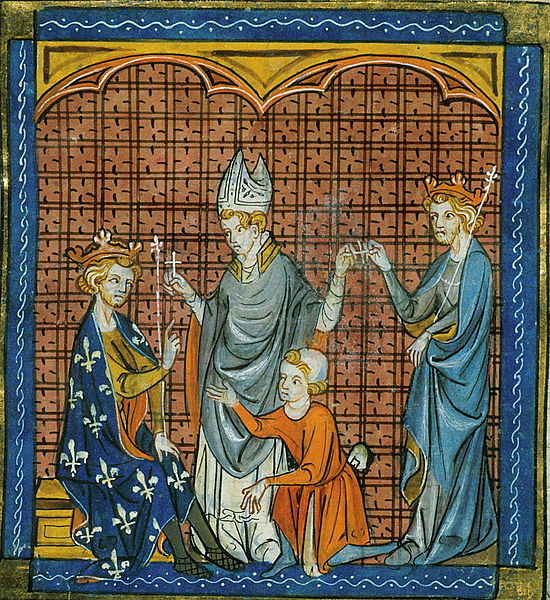

|

| Philip and Henry take the cross |

By 1189 Henry was feeling his years, an old man at the age of fifty-six

and at odds with the majority of his sons. Only base-born Geoffrey stayed true

to his father. Henry tried to keep Richard in check by playing him off against

John. He refused to confirm Richard as heir to the throne of England or to his

French dominions, holding over his head the threat of disinheriting him in

John’s favour.

A new crusade was announced and Richard was eager to win fame and

fortune by the force of his arms. To do so, Richard needed to sort out the

succession issues before he departed for Outremer. Philip too was eager to go

on crusade.

The war between Henry and Philip was renewed; Geoffrey acted as his

father’s chief of staff in this last campaign. Henry sent him to secure his

castles in France and then Geoffrey made for Normandy to alert the garrisons

there.

Henry made for Le Mans, by the

time he arrived he was facing disaster. His troops set fire to the suburbs and

the flames spread into the town itself. Henry was forced to retreat, and

Richard and Philip took his baggage train and followed this up by taking Le

Mans and then Tours.

|

| Chateau de Chinon |

Henry made for his castle at Chinon, but was forced to meet his enemies

for a conference at Ballon. Henry

was so ill he nearly fell from his horse. He was forced to accept humiliating

terms from Philip; he would hand over Alys, Philip would retain his conquests

in Berry and the

Auvergne and Henry would pay 20,000 marks in compensation. Henry was helpless

and raged at Richard;

‘God

spare me until I may be revenged upon you!’[xiii]

Most of Henry’s barons had deserted to the winning side, including John,

Henry’s favourite legitimate son.

Henry returned to Chinon and seems to have suffered a stroke upon

reading the lists of those who had changed sides. His faced changed colour and

his speech was unintelligible. Only Geoffrey was at his father’s deathbed when

on 6th July 1189 Henry was carried on a litter into the castle

chapel where he suffered a further stroke and died.

Henry’s belongings were stolen by the servants and his corpse was left

dressed only in a shirt and breeches. The new king left Geoffrey to arrange Henry’s

funeral; he was buried at Fontrevault Abbey. Unlike

his half-brothers Geoffrey was devastated by the loss of his father and

protector.

Bibliography

Philip

Augustus – Jim Bradbury, Longman 1998

King John –

Stephen Church, MacMillan 2013

Early

Medieval England – MT Clanchy, The Folio Society 1997

Richard the

Lionheart – John Gillingham, George Weidenfeld and Nicholson 1989

The Royal

Bastards of Medieval England – Chris Given- Wilson and Alice Curteis, Barnes

& Noble Books 1995

The

Plantagenets – Dan Jones, William Collins 2012

Henry II –

WL Warren, Yale University Press 2000

King John –

WL Warren, Yale University Press 1997

Eleanor of

Aquitaine – Alison Weir, Jonathan Cape 1999

The

Plantagenets – Derek Wilson, Quercus Editions Ltd 2014

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

Comparisons of wealth are not calculated for before the year 1270, but if

Geoffrey’s income had been granted in that year, not 1181 then the relative

worth in 2014 would have been; historic standard of living value of that income or wealth is £555,500.00 labour earnings of that income or wealth is

£9,800,000.00 economic status value of that income or wealth is £23,220,000.00 economic power value of that income or

wealth is £189,300,000.00 www.measuringworth.com

[iii]

Henry II - Warren

[iv]

Junior king of France from November 1179 and Senior king from 18th

September 1180

[v]

Henry II - Warren

[vi]

King Philip immediately claimed Arthur as his ward, but Henry refused to allow

this

[vii]

Eleanor of Aquitaine - Weir

[viii]

One of Louis VII’s children by his second wife

[ix]

Following an agreement in January 1169 between Louis and Henry that Alys would

marry Richard

[x]

While on crusade he claimed that Henry had fathered a bastard on Alys

[xi]

It has been alleged that Richard was homosexual, this comment from Richard of

Howden being taken as evidence in the theory’s favour

[xii]

Philip Augustus - Bradbury

[xiii]

The Royal Bastards – Given-Wilson & Curteis

How different things might have been if Geoffrey could have been legitimised ... A most unpleasant and dysfunctional family.

ReplyDelete