|

| Henri |

Foreign Policy

François was

willing to ally with anyone who would help bring the emperor low; in 1531 he

allied himself with the German Protestant princes angered by Charles V’s brother Ferdinand’s election as King of the Romans[i]. But the alliance fell out over

François’ treatment of his own protestant subjects.

The Affair of the Placards led to savage persecution of the Huguenots which undermined French relations with their protestant allies. Europe

was further shocked by the contrast between this and François’ alliance with

the infidel Ottoman Empire, interfering with the Hapsburg lands

in Hungary. When in 1535 Charles V decided to

act against the Barbary pirates in the western Mediterranean it provided François with an excuse for yet another fight

with his opponent, saying;

‘If the emperor arms, I

cannot but do the same.’[ii]

Charles took

Tunis, but François failed to take advantage of his absence having

given a promise not to do so, much to the chagrin of Admiral Chabot and his group of warmongers.

In February

1536 when the Duchy of Milan fell vacant François invaded Duchy of Savoy whose ruler was Charles V’s brother-in-law. By May France

and the Holy Roman Empire were at war in all but name. When the imperial army

marched into Piedmont the Marquis of Saluzzo, leading the French forces, defected to the enemy. At the end of March

the French had overrun the duchy. Charles countered this move by having Henri of Nassau invade northern France.

Death and the Dauphin

|

| The Dauphin Francois |

By August

1536 François and the boys were in Lyons, well back from the fighting[iii].

On 1st the Dauphin played a game of tennis with one of his

gentlemen; after the match he sent his secretary Sebastian de Monteccucoli [iv]for

a glass of iced water[v]

and immediately collapsed after drinking it. Young François developed a high

fever and was moved to Tournon. He died on 10th August[vi].

François had

only been informed that his son was unwell[vii],

and now it fell to the Cardinal of Lorraine[viii] to inform the king that his heir was

dead. François may have felt guilty about his many carpings about what he saw

as the Dauphin’s failings following his return from Spain. His opinion of his

heir had mellowed since then, but now François turned to his least favourite

son to inform him and his wife that they were now the Dauphin and Dauphine of

France. François then lectured Henri;

‘Do all that you can to be

like he was, surpass him in virtue so that those who now mourn and regret his

passing will have their sorrow eased. I command you to make this your aim with

all your heart and soul.’[ix]

This advice

from a father who normally did his best to ignore Henri’s very existence must

have seemed like hypocrisy to the grieving adolescent. François did not extend

his love and affection to Henri, he gave that to Charles, which was to

exacerbate the ill-feeling and rivalry between the two remaining brothers.

Suspicious Minds

|

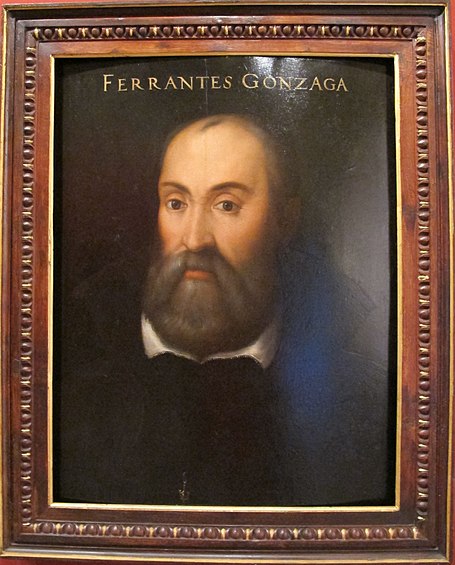

| Ferrante di Gonzaga |

The whole

court attended the death of Monteccucoli; as a regicide he was dismembered with

extreme violence on 7th October 1536 at Lyons. Following

Monteccucoli’s execution a distraught François wrote to all the Protestant

princes in Germany detailing his son’s death and laying the blame on two

imperial generals Antonio de Leyva[x] and Ferrante di Gonzaga.

Gonzaga

protested vigorously against the infamies laid at his door, even to the extent

of having his cousin, the Duke of Mantua send an ambassador to defend his

cousin at the French court. Some hard liners were demanding punitive action

against the Holy Roman Emperor.

In return

the imperialist apologists pointed out that the two people who benefitted from

the Dauphin’s death were the new Dauphin and his wife, who was an Italian and

all Italians were well-known to be poisoners. There were those at court who

were only too ready to turn suspicious eyes on the new Dauphine.

Catherine

found her new position as second lady of France, after Queen Eleanor, under

threat. For himself François paid no attention to the imperialist accusation;

he seemed taken with his son’s wife and Catherine was allowed to join the

ladies who followed the leader of the court, the Duchess d’Étampes To consolidate her own

position Catherine, now three years a wife without sign of a child, needed to

get pregnant; any value she had had as Duchesse d’Orléans was lost as Dauphine.

Henri’s Lover

|

| Diane de Poitiers |

Although she

was a favourite of François’ Catherine was not to Henri’s taste; she did not

attract him sexually, she was not of royal birth and her dowry had never

materialised[xi].

Instead Henri turned to an older woman; Diane de Poitiers, with whom Henri was to stay in love with all his

life. Diane always wore black and white, in mourning for her husband[xii].

Diane was

one of Queen Eleanor’s ladies-in-waiting and was nearly nineteen years older

than Henri who became her devoted admirer. It is believed that she did not

become his mistress until 1538. Being Henri’s mistress was to earn Diane the

undying enmity of the Dauphine.

Diane was

the daughter of Jean de Poitiers, the Seigneur de Saint-Vallier. It

was rumoured that Diane had been one of François’ mistresses before becoming

his son’s lover. In 1552 Lorenzo Contarini, ambassador from the Venetian Republic reported back home;

‘Having been left a widow[xiii],

young and beautiful, she was loved and tasted by the King François[xiv],

and by others also according to what everyone says. Then she passed into the

hands of the present King when he was only Dauphin.’[xv]

Further

rumours claimed that François, annoyed with Henri’s melancholy and uncouth

manner had Diane engage Henri’s affections that she might give the Dauphin some

polish.

Taking the Fight to the Enemy

While

François had been fighting in the north the imperial army had planned an

invasion of Provence where Anne de Montmorency lay in

wait. The imperialist armies crossed the French border on 13th July.

Charles was able to lead his army to Aix-en-Provence but could get no further. The supply chain[xvi]

was ravaged by starving peasants and the local towns were said to be

impregnable. Charles waited at Aix, hoping for the French to proffer battle.

Henri begged

his father to be allowed to join Montmorency in Provence, but François was

determined not to lose another son. Eventually he was worn down by Henri’s

determination and in September Henri was permitted to march south to where

Montmorency was following a scorched earth policy that eventually drove the

imperial army back to Italy.

|

| Chateau d'Ecouen |

Campaigning

together cemented the friendship between Montmorency and Henri; Henri wrote to

Montmorency;

‘Be sure that whatever

happens, I am and shall be for my life as much your friend as anyone in the

world.’[xvii]

Henri was to

remain true to his word.

While

campaigning in Italy Henri got the sister of his one of his Piedmontese grooms

pregnant[xviii].

Filippa Ducci had been a virgin before meeting the prince who apparently only

spent one night in Filippa’s bed. This upped the pressure on Catherine to

produce an heir[xix].

After the campaign in the south Diane became Henri’s mistress; Montmorency

loaned his chateau at Écouen[xx] for their trysts. Henceforth Henri too

was to wear only black and white and took the crescent moon as his emblem.

Bibliography

Martyrs and

Murderers – Stuart Carroll, Oxford University Press 2009

Catherine de

Medici – Leonie Frieda, a Phoenix Paperback 2003

Charles V –

Harald Kleinschmidt, Sutton Publishing 2004

French

Renaissance Monarchy – RJ Knecht, Longman Group 1996

The Rise and

Fall of Renaissance France – RJ Knecht, Fontana Press 1996

Catherine

de’ Medici – RJ Knecht, Pearson Education Ltd 1998

A History of

France – David Potter, The MacMillan Press 1995

Prince of

the Renaissance – Desmond Seward, MacMillan Publishing 1973

Emperor Charles

V – James D Tracey, Cambridge University Press 2010

Henri II – H

Noel Williams, Methuen and Co 1910 (reprint 2016)

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

The title of the future Holy Roman Emperor

[ii]

French Renaissance Monarchy - Knecht

[iii]

The army considered the king as a symbol of bad luck following the battle of

Pavia and his generals had persuaded François, eager to regain his early glory,

to stay away from the battlefield

[iv]

Monteccucoli had previously served Charles V, but had come to France in the

service of Catherine de’ Medici. A book of toxicology was found in his

apartment (a common interest among Italians at the time) and he was accused of

poisoning the Dauphin, something he admitted to under torture but later

recanted.

[v]

François rarely drank wine but drank what the court considered immoderate

amounts of water

[vi]

With François’ death Brittany became part of France, losing its separate status

it had hitherto enjoyed

[vii]

Possibly tuberculosis,

contracted in the damp cells of the Spanish castles he was imprisoned in

[viii] Uncle of Henri’s friend François de Guise

[ix]

Catherine de Medici - Frieda

[x]

Who had died the previous month

[xi]

Her uncle the pope had died in 1534, after which the de’ Medicis lost any strategic

interest in Catherine

[xii]

There are several portraits of Henri in dressed in white or black to compliment

her

[xiv]

Very possibly nothing more than an idle rumour to hurt the reputation of the

king’s mistress

[xv]

Henri II - Williams

[xvii]

Catherine de Medici - Frieda

[xviii]

Filippa had a daughter named Diane de France who

Henri legitimised and married off to Orazio

Farnese Duke of Castro.

Filippa was pensioned off and sent to a convent while Diane was brought up by

Diane de Poitiers. It was rumoured that Diane de France was Diane’s child by

Henri

[xix]

Henri and Catherine were married ten years before Catherine had her first child

[xx]

North of Paris

Hello, did I miss something? Monteccucoli gets an overheated prince a glass of iced water and the young idiot dies of shock and suddenly Monteccucoli is a murderer? er, on what evidence?

ReplyDelete